On June 18th in 1998, Cash Money Records signed a now legendary pressing and distribution deal with Universal Records for a gargantuan $30 million. The move allowed the New Orleans-based hip-hop label, founded and run by Bryan “Baby” Williams and his brother Ronald “Slim” Williams, to move up to that fabled next level, and helped propel a quartet of teenage rappers known as the Hot Boys to megastar status. Barely a month after inking the deal, the photographer Richard Ross travelled from New York City to New Orleans to document the Cash Money crew, capturing key players in candid poses on their home turf. A series of previously unpublished photos from the shoot have now been given a fresh life as the Ca$h Money Rule$ zine.

Advertisement

Originally commissioned by the London-based Trace magazine, Ross says the publication’s editor at the time, Smokey Fontaine, played him “this little promo tape” of the Cash Money roster. It included the Hot Boys’ “We On Fire,” which featured Lil Wayne, B.G., Juvenile, and Turk stuntin’ over a popping, metallic Mannie Fresh beat. “I knew nothing about it but it reminded me of the energy of reggae and soca mixed in with hip-hop,” says Ross. “It was fresh high energy.”

Photograph by Richard Ross

Touching down in New Orleans, Ross was picked up at the airport in a 4x4 commandeered by Baby himself. “He was quiet, low key, on point, and he was the alpha of the group,” Ross reflects. “Everybody gravitated around him.” The plan was for Ross to meet Baby, Slim and the Hot Boys the next day at the Cash Money offices in a suburban neighborhood—but true to hip-hop’s flaky organizational ethos, not everyone turned up. The session ultimately focussed on the Big Tymers, which consisted of Baby and Mannie Fresh, and then Lil Wayne and Slim, who handled the business side of the Cash Money enterprise.“Lil Wayne was in his soldier rags, he had Girbaud jeans, a tank top, some camouflage and Reeboks on,” recalls Ross, adding that the fashion there and then was white t-shirts adorned with iced-down pendants. “Wayne had his little crew. He was cool but he didn’t stay long and kinda dipped out on me. I definitely got that energy from Wayne when he walked in the room, but I made the mistake of using the bathroom and when I came back out he was gone!”

Advertisement

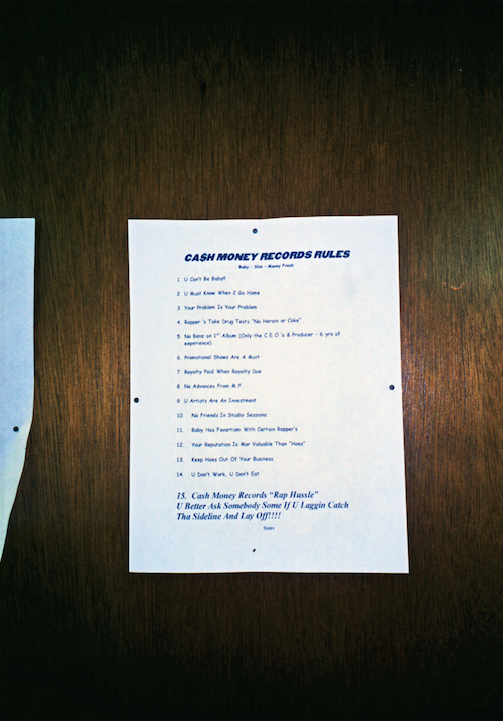

The Cash Money headquarters at the time was decorated with posters of UNLV, one of the label’s early key acts, along with photographs of stacks of coins and mountains of dollar bills. The doors to Baby and Mannie Fresh’s offices were adorned with lists of rules (which inspired the title of Ross’s zine). Baby’s included commandments like, “No Benz on 1st album,” “U don’t work, U don’t eat,” and “Royalty paid when royalty due.”Over eight hours, Ross was allowed to tag along with the Cash Money crew as they went about their business, stopped by Popeye’s for lunch, and hung around outside Baby and Slim’s aunt’s house in the 4th Ward. He says this access fit in with his style of photography, which taps into a laid back, documentary vibe. “The gangsta persona, I don’t really like to play that up,” he explains. “I photographed them as real people. They weren’t playing the tough guy role, they were really up on their shit and nice people, a total 180 from what I would get when I photographed other hip-hop acts in New York.” Ross adds that he was using point-and-shoot cameras, which kept his subjects unguarded: “When people see big cameras they get really tight and anxious and want to put their best foot forward when it should be like, just be yourself.”

Photograph by Richard Ross

Nearly two decades on from the original shoot, the photos of the Cash Money icons convey a mix of carefree innocence and the breezy confidence of success. Baby stunts in a portrait with a Rolex on each arm played against a plain white tee, while he holds up an oversized brick cellphone complete with antenna. Ross says that the crew claimed two versions of the Cash Money pendants, one iced-out and the other with a black onyx background, estimated to have cost around $15,000; when Mannie Fresh displays his, the relatively small size of the piece comes off as quaint when set against the ginormous chains rappers would soon begin to flaunt.“The vehicles Cash Money had and the jewelry, everything was understated but over-the-top,” says Ross summing up his snapshot of the Cash Money movement. “It isn’t so flamboyant but it was low-key and still original. So the deal [with Universal] was just the cherry on the top because they were already doing that shit for a long time and just like Master P they were selling. They seemed focussed and I’m not surprised that, despite all the legal issues, they’re still selling records and impacting. They’re the last of the Mohicans.”