As a photographer I know how difficult it can be to make a portrait of a stranger that captures their personality and delivers something honest and true about their character. With a subject you don’t know personally, the process requires attention to their disposition and the ability to adapt quickly in order to make them feel as comfortable as they can so you can get the perfect image. Sometimes you have to take the reigns and direct your subject, or if you’re lucky, the chemistry between the two of you is organic. But either way, you must create a photo that encompasses who they are in a single frame.Photographer Deborah Feingold is a master of this. Over the past four decades, she has created iconic images of renowned politicians, actors, and musicians, and has had her work published in places like Rolling Stone, The New York Times, and Village Voice among others. Music, her first photo anthology of photos of musicians, features intimate portraits with legendary artists including Madonna, Prince, Mick Jagger, and Brian Eno.I spoke to Deborah about how creating photos is a lot like writing music, the necessity of prioritizing shooting over sleeping, and making great images—no matter the conditions.Noisey: I read that your father taught you how to develop prints in the dark room in your basement when you were 12. At that age were you interested in becoming a professional photographer or did it seem more like a hobby?

Deborah: I didn’t know it could be a profession! I was born in 1951 and grew up in Rhode Island. Back then, with a hobby, you just loved it; you didn’t think, “How can I make money off of this?” You did things that just gave you so much pleasure and joy. In my case, I didn’t come from a creative family. I came from a working family, lower middle class, so I wasn’t around that kind of encouragement really. It was “You better take typing and get a teaching degree.” So I fulfilled [my parents’] wish on one account—I got a teaching degree—but I never learned how to type. I knew that if I learned how to type, I wouldn’t have a choice but to become a secretary. I didn’t know a lot of people when I was growing up who went into the arts.How did you go from the teaching degree to photographing musicians regularly?

Because I’d been doing photography as a hobby all the time, I worked at a camera store. Everywhere I lived, there was a darkroom in my bedroom, and now I think I don’t remember stuff because of all the chemicals! [Laughs]. I took the hobby with me, never really put together that it was something that could be a career. I was always creating and teaching photo workshops for people, usually those who were disabled. I worked at a nursing home, a Y camp, a lot of places. When I was teaching, I wanted people to learn how to use a camera as a tool to express yourself. It wasn’t technically-oriented.During that time, when I would come home from work every day, I would see a man working on his truck. He was either washing it or fixing it, and long story short: he was a jazz musician who lived in my building, he had a crush on me and he just so happened to be there at 4 o’clock every day when I came home. We eventually became involved with each other, and that kind of turned my world around. I fell in love with him and the lifestyle, the music, and I had never really heard jazz before and I became enamored with the whole process of improvisation. For someone who was really sheltered growing up, this was pretty different. It was a more collaborative process and I was really attracted to it. I started out photographing him and his band while they were playing; searching for photos much like the way they were searching for sound while they played off each other. A real romance evolved and I ended up moving to New York with another musician I fell in love with. He had a friend who was starting his own jazz label, and he got to go on the road with Chet Baker, and I got to do my first real photo session with Chet Baker.

What equipment did you initially use?

What equipment did you initially use?

The first 35mm camera I got was a Yashica that my dad had bought me, and then I had a Honeywell Pentax. When I moved to New York, I saved up my money and bought a Nikkormat. Talk about weight—it was like holding a car around your neck! It was so heavy. For a long time I only had a 50mm lens, no lighting equipment. There’s a photo of Bono in the book that was shot with a painter’s silver reflector and a 100-watt bulb. I learned that I had to shoot him in my apartment and I didn’t have enough light in there, but it worked out! That was good.Did you primarily shoot out of your apartment?

Yeah, Madonna was in my apartment… but everything I owned folded back. My bed folded, my kitchen table folded, so I could just fit in a roll of seamless. By the time you walked in, it looked like a little photo studio. I kind of surrendered—my closet was my dark room—and I never really had my own apartment until I was much older and got a separate photo studio. The priority was always shooting, not where I slept.At what point in your career were these photos of Madonna taken? Had you photographed her before?

It was 1982 and I was working for Musician Magazine. It was the only time that I initiated a photo shoot. I asked Musician if we could shoot her, and they weren’t interested. So I called up a magazine called Star Hits because I was friends with the editor, and I asked him if he would be able to arrange a photoshoot with Madonna, and he said “Yeah, sure.”Madonna showed up with her publicist Liz Rosenberg. There was no make-up artist, no manager, no stylist. I had a young lady who was assisting me at the time in the studio. When Madonna walked in, we said hello, and we went right to work. I shot four rolls of film, and every frame, she posed differently. We both knew we had gotten what we needed, and she left. It was two girls working, there wasn’t a lot of chitchat: we were both there for the same reason. I didn’t pose her, she knew exactly what to do. If we were dancing, she lead and I followed, but I kept up with her beautifully. It was very exciting. There was just something different about her—an aura, a glow, a confidence, something going on that set her apart. And I think people see that in the images. How the hell was she so confident at that point? That’s just who she was, and I think that shows in the film, though it was a very early point in her career.It’s interesting to me that you didn’t have to direct her at all. Do you typically not have to direct your subjects?

I try not to. What I’ve learned is by not offering direction that can mak it incredibly uncomfortable, so sometimes, it’s a generous offering to tell someone what to do. When my subject is just standing there, it can be pretty uncomfortable. So I kinda play it as it lays. I try to assess what their need is.

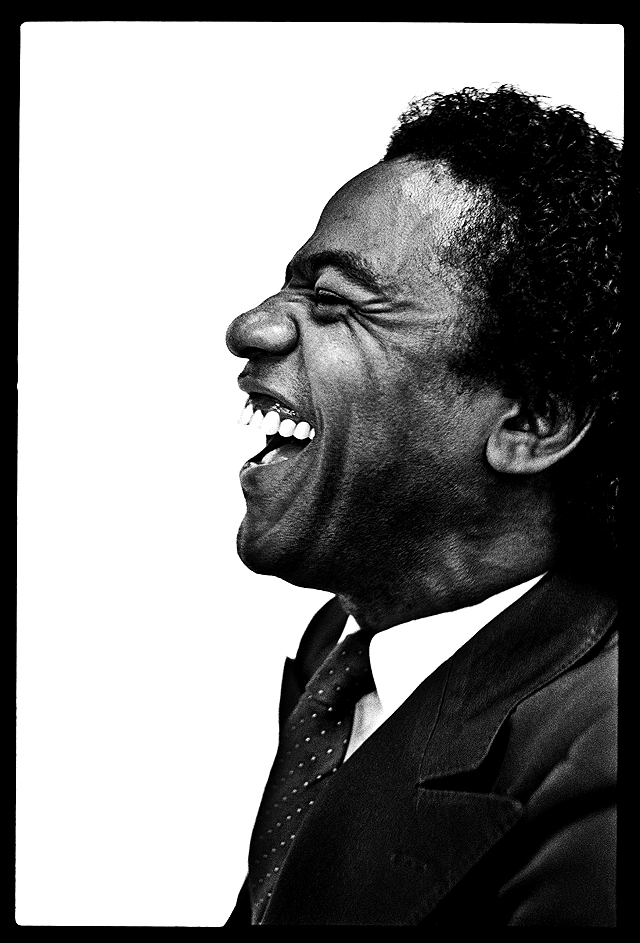

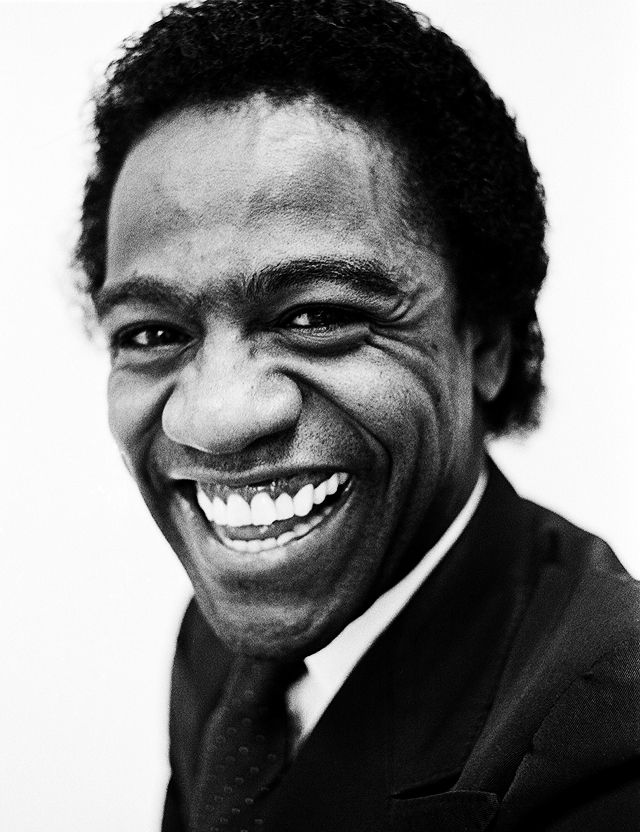

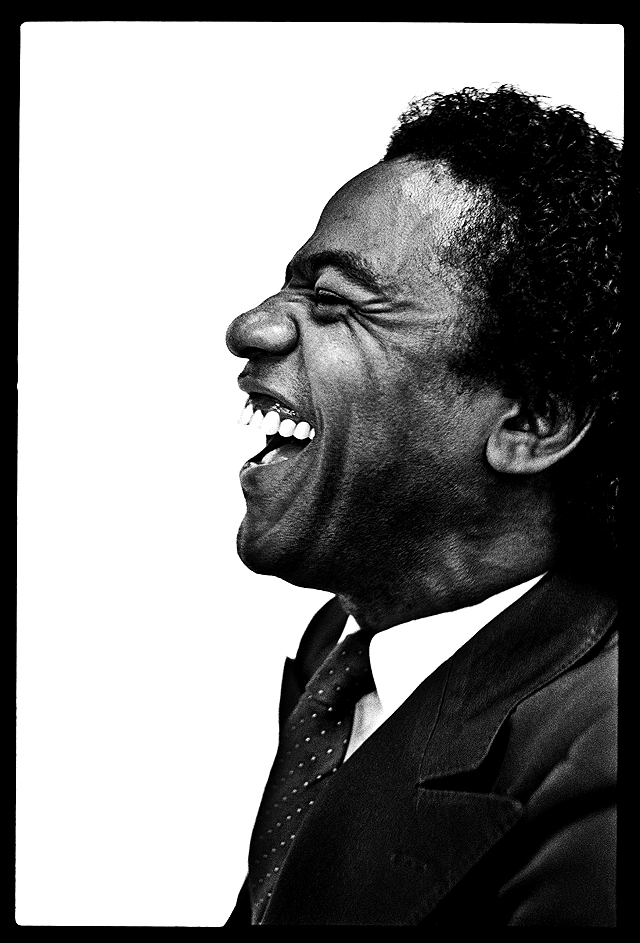

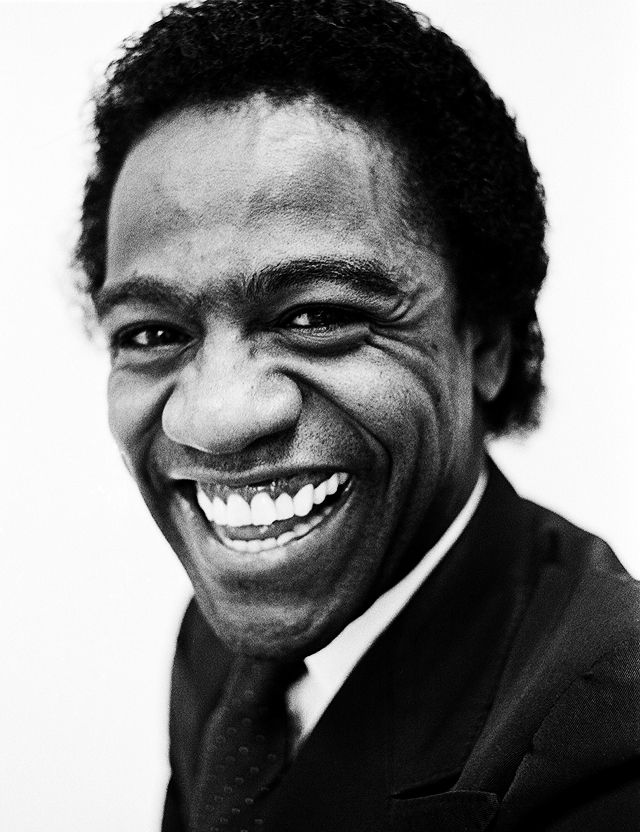

Al Green.

Al Green.

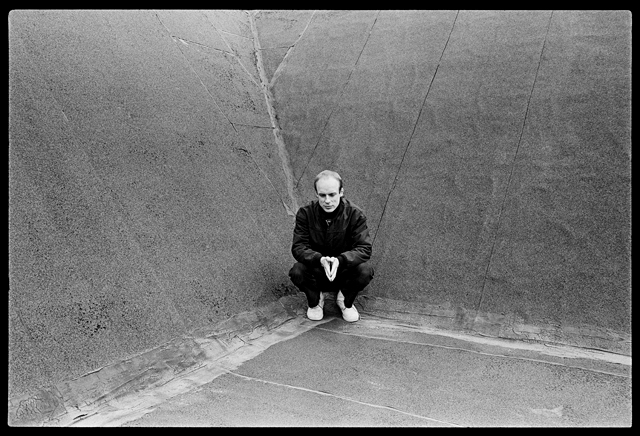

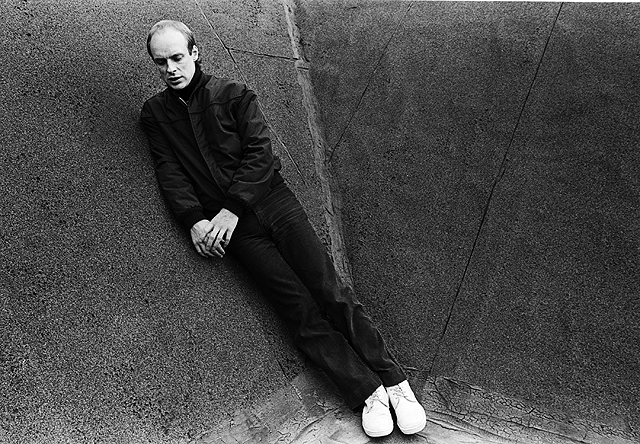

You do a great job capturing the personalities of musicians—for example, Al Green's infectious smile or Brian Eno's more somber state. In these photos, what did you have to do to evoke such expressions?

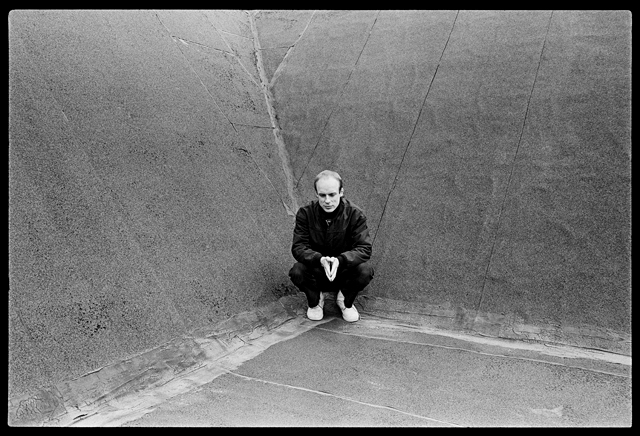

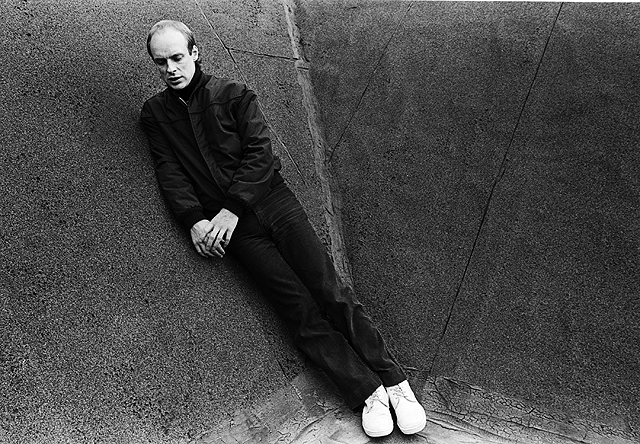

So with Al Green, I actually never spoke to him during that photoshoot. It was during rehearsal for a Broadway play called Your Arm’s Too Short to Box with God in 1982 with Pattie LaBelle. I had a long lens, and I was able to move about while they were rehearsing. The one where he’s laughing in profile, I had no connection to him at all, and the other one I caught when he appeared to be looking at me.What I love the photos of Brian Eno is that both of those shots, to me, reflect his music. He had no problem just leaning on the wall like that. I don’t remember, I could have asked him to do that—I could or I couldn’t have. But either way the photo makes sense. It all makes sense for the type of artist he was and for the way I liked to work. So it was perfect because they’re both musical to me.

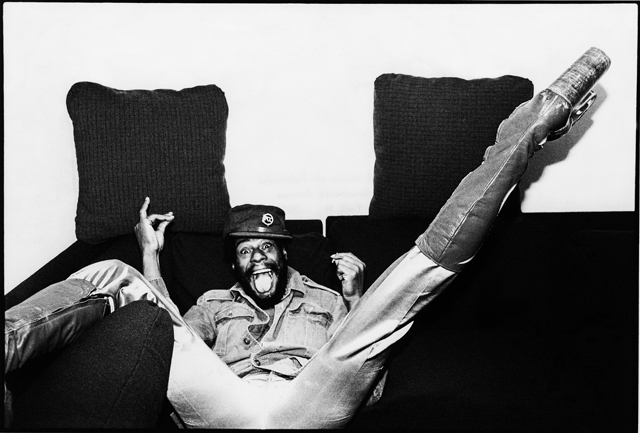

Brian Eno.The images of George Clinton make me think of the Al Green ones; they’re so expressive, and Clinton is particularly wild. Did you have more of a connection with him than you did with Green?

Brian Eno.The images of George Clinton make me think of the Al Green ones; they’re so expressive, and Clinton is particularly wild. Did you have more of a connection with him than you did with Green?

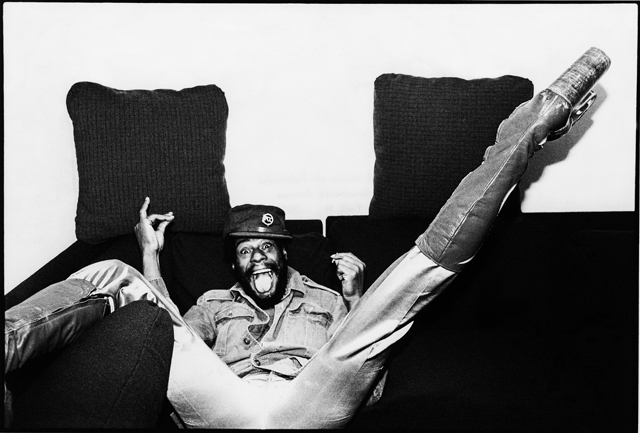

So by the time I started shooting—late 70s, early 80s—no one was paying to go on the road with people you were shooting, and so a lot of photos were shot in the record company offices. The challenge that I gave myself was figuring out how to make sure no one knew where I was. A lot of the time I would bring a canvas backdrop with me. A lot of these photos were for Musician Magazine and we were a smaller magazine. We weren’t getting the access that Rolling Stone was getting, but of course that changed. My challenge, and I was very conscious of it, was “There’s no complaining girl! This is the opportunity of your life. Make it work.” That’s how I still work today. You can put me in an empty box and I can come up with something. I didn’t work with stylists and make-up artists for the better part of my career. There isn’t a crew attached to my photos, usually just me and them, and maybe a writer.The ones with George [Clinton] separated themselves because he made it so easy. There was very little that I had to do. Those were shot in a conference room. The location doesn’t matter; it’s what you do with it. You know, lemons and lemonade. Something that I always wanted to do, but wasn’t always successful with, was make a picture I had never seen before.

George Clinton.You’ve been photographing for so long, and I can only imagine how many photos you have in your archive. What was the editing process like for your new book, Music?

George Clinton.You’ve been photographing for so long, and I can only imagine how many photos you have in your archive. What was the editing process like for your new book, Music?

It was actually so easy. The things that I thought would be impossible were the easiest parts. The editing was super easy. I made a really big edit and then showed it to my dear friend Matt McGinley, who is a couple of decades younger than me and assists me on my shoots. He also is a music photographer himself and he covers mostly rap. He edited with me and I have another friend who edited with me. Matt being in his 30s and loving music, he helped me the most with taking out stuff that I didn’t need to have. He was looking at it all as a photographer and as a music lover.The sequencing I was so scared of. First you sequence the two images that go together, the left and right side. A woman I know who does book cover design and I paired all the images in five hours. A few weeks later we came back and ordered all the images, which took three hours. Then we gave it to the designer who put her spin on it, and it was perfect. I couldn’t believe that that would’ve been the easiest part.As for the cover, there was never gonna be another cover for this book. It was not necessarily the cover that my publisher wanted, but that was always it.

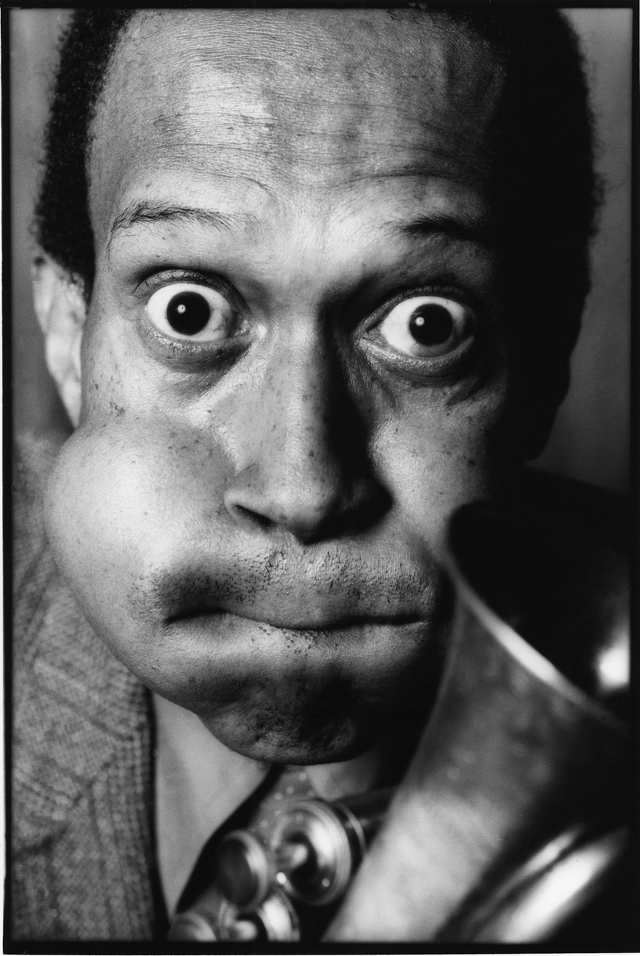

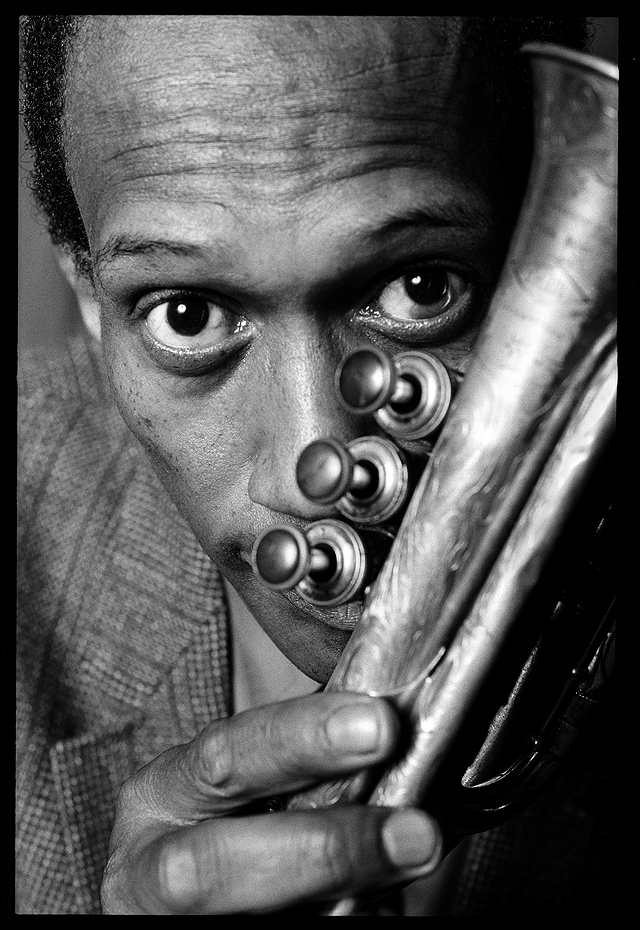

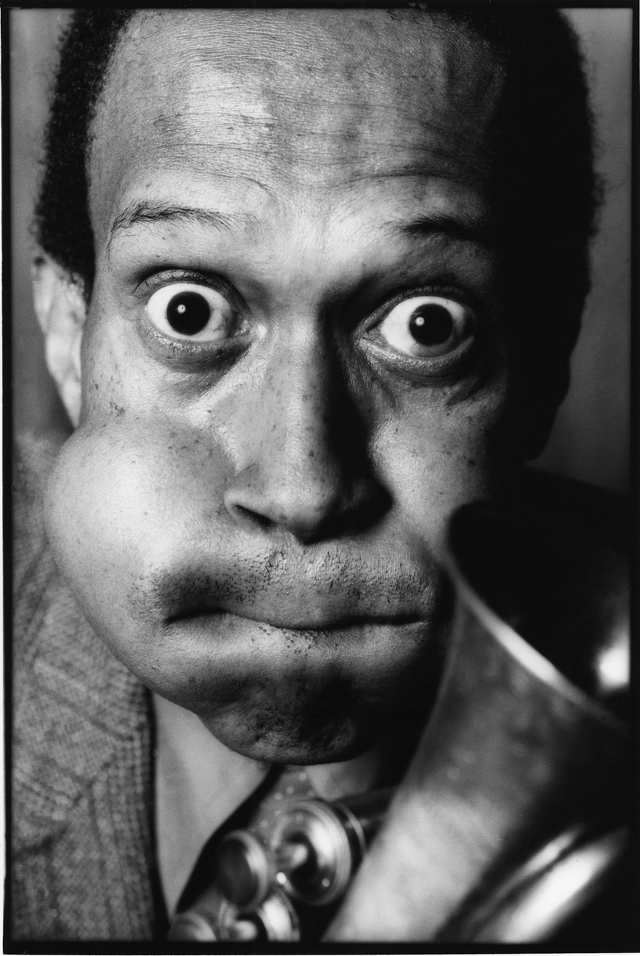

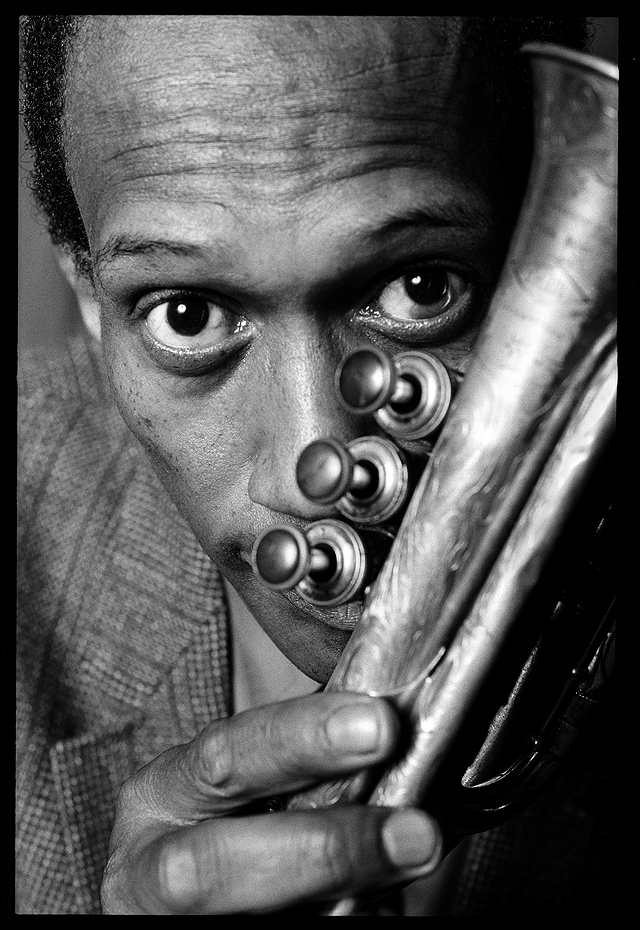

Don Cherry.Music will be out via Damiani Books on September 30.If you’re a musician, Shriya Samavai might want to take your picture. Follow her on Twitter: @shriekeliene

Don Cherry.Music will be out via Damiani Books on September 30.If you’re a musician, Shriya Samavai might want to take your picture. Follow her on Twitter: @shriekeliene

Advertisement

Deborah: I didn’t know it could be a profession! I was born in 1951 and grew up in Rhode Island. Back then, with a hobby, you just loved it; you didn’t think, “How can I make money off of this?” You did things that just gave you so much pleasure and joy. In my case, I didn’t come from a creative family. I came from a working family, lower middle class, so I wasn’t around that kind of encouragement really. It was “You better take typing and get a teaching degree.” So I fulfilled [my parents’] wish on one account—I got a teaching degree—but I never learned how to type. I knew that if I learned how to type, I wouldn’t have a choice but to become a secretary. I didn’t know a lot of people when I was growing up who went into the arts.

Advertisement

Because I’d been doing photography as a hobby all the time, I worked at a camera store. Everywhere I lived, there was a darkroom in my bedroom, and now I think I don’t remember stuff because of all the chemicals! [Laughs]. I took the hobby with me, never really put together that it was something that could be a career. I was always creating and teaching photo workshops for people, usually those who were disabled. I worked at a nursing home, a Y camp, a lot of places. When I was teaching, I wanted people to learn how to use a camera as a tool to express yourself. It wasn’t technically-oriented.During that time, when I would come home from work every day, I would see a man working on his truck. He was either washing it or fixing it, and long story short: he was a jazz musician who lived in my building, he had a crush on me and he just so happened to be there at 4 o’clock every day when I came home. We eventually became involved with each other, and that kind of turned my world around. I fell in love with him and the lifestyle, the music, and I had never really heard jazz before and I became enamored with the whole process of improvisation. For someone who was really sheltered growing up, this was pretty different. It was a more collaborative process and I was really attracted to it. I started out photographing him and his band while they were playing; searching for photos much like the way they were searching for sound while they played off each other. A real romance evolved and I ended up moving to New York with another musician I fell in love with. He had a friend who was starting his own jazz label, and he got to go on the road with Chet Baker, and I got to do my first real photo session with Chet Baker.

Advertisement

The first 35mm camera I got was a Yashica that my dad had bought me, and then I had a Honeywell Pentax. When I moved to New York, I saved up my money and bought a Nikkormat. Talk about weight—it was like holding a car around your neck! It was so heavy. For a long time I only had a 50mm lens, no lighting equipment. There’s a photo of Bono in the book that was shot with a painter’s silver reflector and a 100-watt bulb. I learned that I had to shoot him in my apartment and I didn’t have enough light in there, but it worked out! That was good.Did you primarily shoot out of your apartment?

Yeah, Madonna was in my apartment… but everything I owned folded back. My bed folded, my kitchen table folded, so I could just fit in a roll of seamless. By the time you walked in, it looked like a little photo studio. I kind of surrendered—my closet was my dark room—and I never really had my own apartment until I was much older and got a separate photo studio. The priority was always shooting, not where I slept.At what point in your career were these photos of Madonna taken? Had you photographed her before?

It was 1982 and I was working for Musician Magazine. It was the only time that I initiated a photo shoot. I asked Musician if we could shoot her, and they weren’t interested. So I called up a magazine called Star Hits because I was friends with the editor, and I asked him if he would be able to arrange a photoshoot with Madonna, and he said “Yeah, sure.”

Advertisement

I try not to. What I’ve learned is by not offering direction that can mak it incredibly uncomfortable, so sometimes, it’s a generous offering to tell someone what to do. When my subject is just standing there, it can be pretty uncomfortable. So I kinda play it as it lays. I try to assess what their need is.

You do a great job capturing the personalities of musicians—for example, Al Green's infectious smile or Brian Eno's more somber state. In these photos, what did you have to do to evoke such expressions?

So with Al Green, I actually never spoke to him during that photoshoot. It was during rehearsal for a Broadway play called Your Arm’s Too Short to Box with God in 1982 with Pattie LaBelle. I had a long lens, and I was able to move about while they were rehearsing. The one where he’s laughing in profile, I had no connection to him at all, and the other one I caught when he appeared to be looking at me.

Advertisement

So by the time I started shooting—late 70s, early 80s—no one was paying to go on the road with people you were shooting, and so a lot of photos were shot in the record company offices. The challenge that I gave myself was figuring out how to make sure no one knew where I was. A lot of the time I would bring a canvas backdrop with me. A lot of these photos were for Musician Magazine and we were a smaller magazine. We weren’t getting the access that Rolling Stone was getting, but of course that changed. My challenge, and I was very conscious of it, was “There’s no complaining girl! This is the opportunity of your life. Make it work.” That’s how I still work today. You can put me in an empty box and I can come up with something. I didn’t work with stylists and make-up artists for the better part of my career. There isn’t a crew attached to my photos, usually just me and them, and maybe a writer.

Advertisement

It was actually so easy. The things that I thought would be impossible were the easiest parts. The editing was super easy. I made a really big edit and then showed it to my dear friend Matt McGinley, who is a couple of decades younger than me and assists me on my shoots. He also is a music photographer himself and he covers mostly rap. He edited with me and I have another friend who edited with me. Matt being in his 30s and loving music, he helped me the most with taking out stuff that I didn’t need to have. He was looking at it all as a photographer and as a music lover.The sequencing I was so scared of. First you sequence the two images that go together, the left and right side. A woman I know who does book cover design and I paired all the images in five hours. A few weeks later we came back and ordered all the images, which took three hours. Then we gave it to the designer who put her spin on it, and it was perfect. I couldn’t believe that that would’ve been the easiest part.

Advertisement