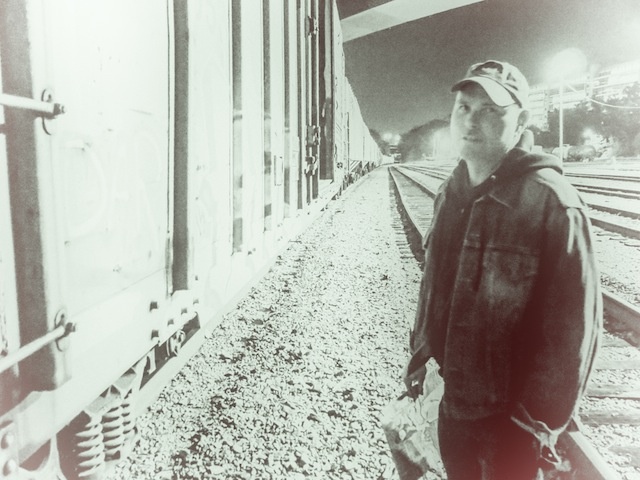

Tiny avalanches of grey rocks and dust follow Tim Barry down a steep hill under the mask of darkness. “The best way to do it is to crabwalk it,” he says as he descends the stones on the heels of his shoes and the palms of his hands, a slight hint of moonlight guiding his way. “Oh, by the way,” he calls back, as though it’s understood, “this is illegal.”

We get down to the bottom and Barry wipes his hands off on the thighs of his black Carhartt pants as he steps over some abandoned blankets and crushed beer cans. The coast is clear in either direction. He walks straight towards the lone freight train in the rail yard, which sits on the farthest track, and begins reading the sides of the cars.

Videos by VICE

What would look like random scribbles and scrawls to the average person are a living language to him. He reads them like hieroglyphics and tells the story of each one. “This guy is from Canada,” he says, putting his knuckle on a moniker marked on the side of the steel boxcar. It echoes hollow inside as he taps it. “This guy was from here in Richmond and moved up to New York a couple years back.” One is signed “Conrail Twitty,” the moniker of Travis Conner, Barry’s friend and train-hopping brother who took his own life six years ago. Barry found him in the woods, hanging from a tree.

A headlight shines on us from the distance and Barry doesn’t like the look of it so we duck between cars. “Don’t worry, there’s no air in the train,” he says to assure me that the train will not suddenly take off and crush us both—he has had friends nearly lose legs to trains. We cross over the coupler that links the cars and hop onto the other side, out of sight. The rocks crunch as we land between the far side of the train and the James River, which Barry memorialized by naming an album after it while fronting the long-running now defunct punk band, Avail. “Let’s just wait here a minute,” he says while cracking open—as if from nowhere—a can of Miller Lite, the alcoholic beverage of choice for a diabetic like Barry. “If I think I see the cops or something, I usually wait it out about ten minutes.”

Ten minutes turn into a few hours as he goes through a seemingly endless supply of cans from the pockets of his jean jacket and an equally endless supply of train-riding stories.

At 43, the punk elder statesman has lived his fair share of lives. For nearly 20 years, Avail endured as one of the most well-respected bands in punk, leaving their mark around the world, known for their cathartic, sweaty live shows and workmanlike DIY ethic. In the process, they built a passionate international fanbase, but perhaps more significantly, helped establish their home base of Richmond as a city with a respected music scene, in which they became iconic.

For as much as he loves Richmond, Barry is a known wanderer. He’s traveled the globe several times over and has the stories to prove it—some details he’ll go off on for 20 minutes, and others he prefers to cut short, like when he casually mentions that he’s spent a bit of time “locked up.” When pressed on why, he looks down and replies diplomatically in his southern accent, “Well. Everyone down here does something stupid at one point or another” and goes back to his original story.

Over the last decade, from the ashes of Avail, Barry has carved out a new role for himself in the music scene, trading in the members of his band for an acoustic guitar, and embarking on a solo folk career, without sacrificing much of the grit and no-bullshit attitude that gained him a rabid following in the first place. Many of his early solo songs sounded like stripped down versions of the punk anthems fans grew to love.

In front of the microphone, he has the onstage presence of an evangelist preaching a religious sermon. He delivers the gospel in between songs—dispensing life advice, telling stories, and promoting his live-first-work-second philosophy. “Fuck yeah!” he’ll frequently say after a song finishes. “Y’all know I don’t believe in how music sounds, it’s how it feels. And that felt fuckin’ right.” If you’ve ever wanted to see a crowd of grown, bearded men tear up while sipping beer, Barry’s live show is the place for you.

He pulls himself up into an empty boxcar and winces when he leans on his right hand. A few years back, Barry was playing a show in Canada and was telling the audience about how he wrote the song “Wait at Milano” in memory of Conner. A drunken heckler kept shouting to interrupt. Barry snapped, charged after him, and—as one does when having their dead friend mocked—broke his fist on the guy’s head. “It was stupid and I regret it.” Barry takes a sip from the can and looks up at the underside of the Robert E. Lee Bridge. “Actually nah, fuck him,” he laughs. “He had it coming.”

Barry doesn’t have much time for nights like these anymore.

They say you’re very Richmond if you can tell which way the wind is blowing by the smell. The city formerly housed a Lucky Strike factory and Reynolds Wrap factory and is still home to various paper mills. So depending on the wind, true longtime residents would be able to pick up on the manufacturing scent of cigarettes or the hint of sulfur from the mills.

Anyone familiar with Barry’s music knows how synonymous he is with the city. Barry—who has the words “Richmond, Virginia” tattooed on his left arm and a train crossing over the James River above the Virginia state motto “Sic semper tyrannis” on his right—is something of a local historian and has practically written the guidebook to the area. Between his solo work and his time in Avail, every major Richmond spot has been paid homage to by Barry, whether it be by a song title, a lyric, or a photo in a record sleeve—Lombardy Street, Monroe Park, VCU, he’s hit them all. Hell, he even named an album after the cross streets where his house is located.

It’s Saturday and Barry begins the day—as he does everyday—by going for an early morning run through the neighborhood with his dog, Emma. Typically, Saturdays are his designated “days off” and for a musician who is his own booker, manager, agent, publicist, and warehouse, that’s a rarity. “It’s like having seven different jobs,” he says. “When people ask what I do, I never tell them I’m a musician. I say I do ‘retail music management.’ You gotta know everything—from auto mechanics to songwriting, to instrument repair, to booking, to corresponding, to press, tour management, retail, merchandising, shipping, everything.” He recently learned how to set his email’s out-of-office response—any emails received today get the auto-response: “Gone fishing.”

This being the last Saturday before he leaves for tour, he doesn’t have much time to relax between all the loose ends that need wrapping up. He goes into the shed in his backyard which, for three years, formerly served as a makeshift home for him, very much exemplifying the “living simple” philosophy he is known to advocate. But since moving into the house, the shed now acts as a practice/storage space. Boxes filled with t-shirts and merch items are stacked up against the wall where his bed used to be. He recently taught himself the fine art of making tie-dye shirts, which started as a joke but seemed to resonate among fans. He counts out a few in each size and lays them on a stack of chairs next to some paint cans and his acoustic guitar. He takes a break, sits down on a lawnmower box, and flips through his phone for messages as he sneaks a cigarette. There’s an offer to play in Spain he’s not too enthused about and a problem with one of next week’s shows. He takes a drag and reads another.

He stops suddenly as a young voice yells excitedly from the backyard: “Daddy?”

“Shit,” Barry whispers under his breath. He quickly butts his cigarette out on his workbench and rubs a dab of Purrell into his hands. “Back here, monkey!” he calls back. His two-year-old daughter, Lela Jane, has found him.

She wants him to join her in one of their favorite shared activities: singing a song from the Disney movie, Frozen, a new addition to Barry’s repertoire. Here stands a punk icon, a man who wrote the raucous anthems and righteous lyrics countless fans have tattooed on their skin, holding a small child, singing: “Do you wanna build a snowman?” As Lela runs off to chase the dog, he looks at me and says, “I mean, it is a catchy song.”

Sarah, Barry’s wife, is not far behind, walking at a slower pace, with one hand over her stomach. She is eight months pregnant and Barry is leaving for a week-long tour in three days. He has arranged it so that he is never more than a 10-hour drive from home and can head straight back if there’s an emergency.

Over the last few years, as Barry has transitioned from living in the shed to living in the actual house which Sarah owns, she and Lela have become a more frequent presence in his music. Gradually, a new Tim Barry—Tim Barry the family man—has emerged in his songs. A far stretch from the hard strumming, hard travelling loner presented in his early solo work.

His earlier solo recordings had a palpable undertone of drunken anger. “Avoiding Catatonic Surrender,” for example, a fan favorite shout-along about being drunk and alone in a New Jersey motel begins with Barry mumbling away from the microphone: “I fucking hate this song. Pain in my ass.” But on his new album, Lost & Rootless, which he is releasing this year, he sounds a lot happier while picking along to tracks like “Older and Poorer,” a song he wrote for Sarah as a two-year wedding anniversary gift. You can actually hear his smile as he sings giddily:

“Before we hit middle age, there’s one thing left I’d like to say,

I loved you from the first time I saw your face.

Though I’ve annoyed you ever since, I’m thankful that we are still friends.

And growing older and poorer with grace.”

Even his album covers hint at a more family-focused artist. The cover of Rivanna Junction, Barry’s first proper solo album released in 2006, featured a gray sepia-tinted photo of himself, looking tired and grizzled, standing alone on a freight train. The same gray filter tints the cover of Lost & Rootless but the lone Barry has been replaced by a picture of Sarah, standing in their backyard, smiling, and holding an infant Lela.

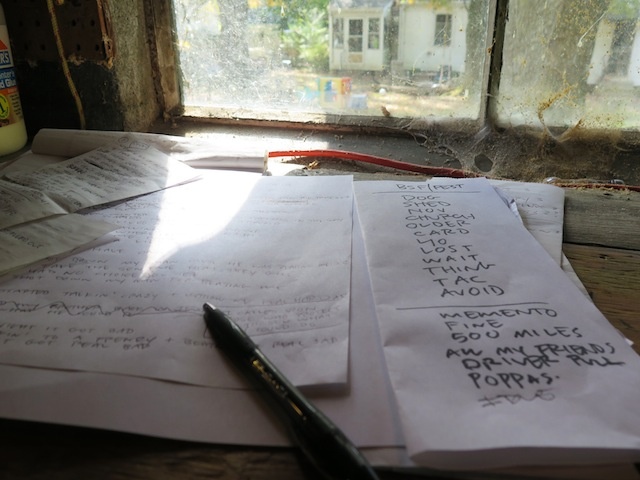

“Merch orders” is one of the items on the to-do list in Barry’s notebook, which Lela has scribbled all over with a pen. He carefully lays out some tie-dye shirts to ship out and Lela helps by completely rearranging them.

This has been the first year where he has been able to sustain himself entirely on his music career, without having to pick up supplementary odd jobs in his off-time. But as the size of his family increases, the question hangs overhead: How long can a touring musician playing to mid-level venues support a family? He doesn’t seem worried. “I have never in my life had a regular paycheck,” says Barry, who is quick to point out that while he never had a bank account until recently, he’s also never been in debt. “I am so comfortable with the idea that I can pull shit off that I’ve never made a long-term financial plan. With music, I have never set a deadline for when I’m gonna stop playing. I just know that one day, I’m gonna wake up and go. ‘I can’t do this anymore.’ And that’s it.”

“Truthfully, I’m just figuring life out as it comes. I just believe in being good to the people I’m surrounded by. I know that sounds hippie or peace-punk or whatever. I’d just rather work than force music.”

Barry maintains that being married and having a growing family has not directly slowed down his adventurous soul-searching nature, either. He’ll still hop the occasional train to the unknown or take a canoe out on the river and spend the night on a nearby island. “When we were exchanging our vows in Sarah’s mother’s backyard, Sarah looked at me and said, ‘I know that you have a wanderlust and are gonna keep traveling and moving around. And I accept that,’” he recalls. But lately, the freedom seems like the lesser option.

“As you continue on with life, you go through different phases,” he explains. “A couple weeks ago, I was sitting down at the yard trying to catch a simple turn train and a graffiti artist walked up and said, ‘Where you going, Tim?’ And I said, ‘Oh, I’m just trying to catch the turn train.’ And as soon as it got aired up and ready to go, I looked at him and said, ‘I don’t even think I wanna do this. I’d rather be at home.’”

Back at the rail yard, the night has grown windy and colder.

Barry talks about the following year. He already has it mapped out. He leaves for England in February. Then onto the West Coast, the Southwest, the Midwest, up to the Northeast and Canada, with some fly out dates to Texas in between.

As we walk along the stones, Barry spots something a few yards away that makes him stop. A family of deer has made its way onto the tracks, standing just a few feet from the lone train.

“Look at ’em!” he points towards the three of them. “They see us. They ain’t even scared.” He watches them for a moment in silence and they stare back at us. The faun scurries off and the other two chase after it.

A breeze shakes the branches of the surrounding trees in the night. Barry’s nostrils flare to take it in, exposing a hole in his septum where a piercing used to hang back in his Avail days. The air smells of sulfur. In 20 days, he and Sarah will welcome a new addition to the family, a girl—Coralee Hall Barry.

He decides it’s time to head home.

Dan Ozzi is on Twitter – @danozzi

More

From VICE

-

Mike Ehrmann/Getty Images -

littlebloke/Getty Images -

AEW