A shorter version of this story appears in VICE magazine and Noisey's second annual Music Issue. Click HERE to subscribe to VICE magazine.A strange and unexpected thing happened to punk in 1994—it got popular. Albums like Green Day’s Dookie and the Offspring’s Smash rode the tail end of the 90s grunge wave to mainstream success and sold millions of copies in the process. America’s interest in the poppier, more commercially friendly version of the once underground genre was piqued. While a small handful of acts became megasellers, countless other punk bands waited in the wings, hoping to get noticed. Up-and-coming punk labels realized they were sitting on rosters stacked with potential breakout stars, and a decade-long industry phenomenon centered on cheap punk compilation CDs was born.

Advertisement

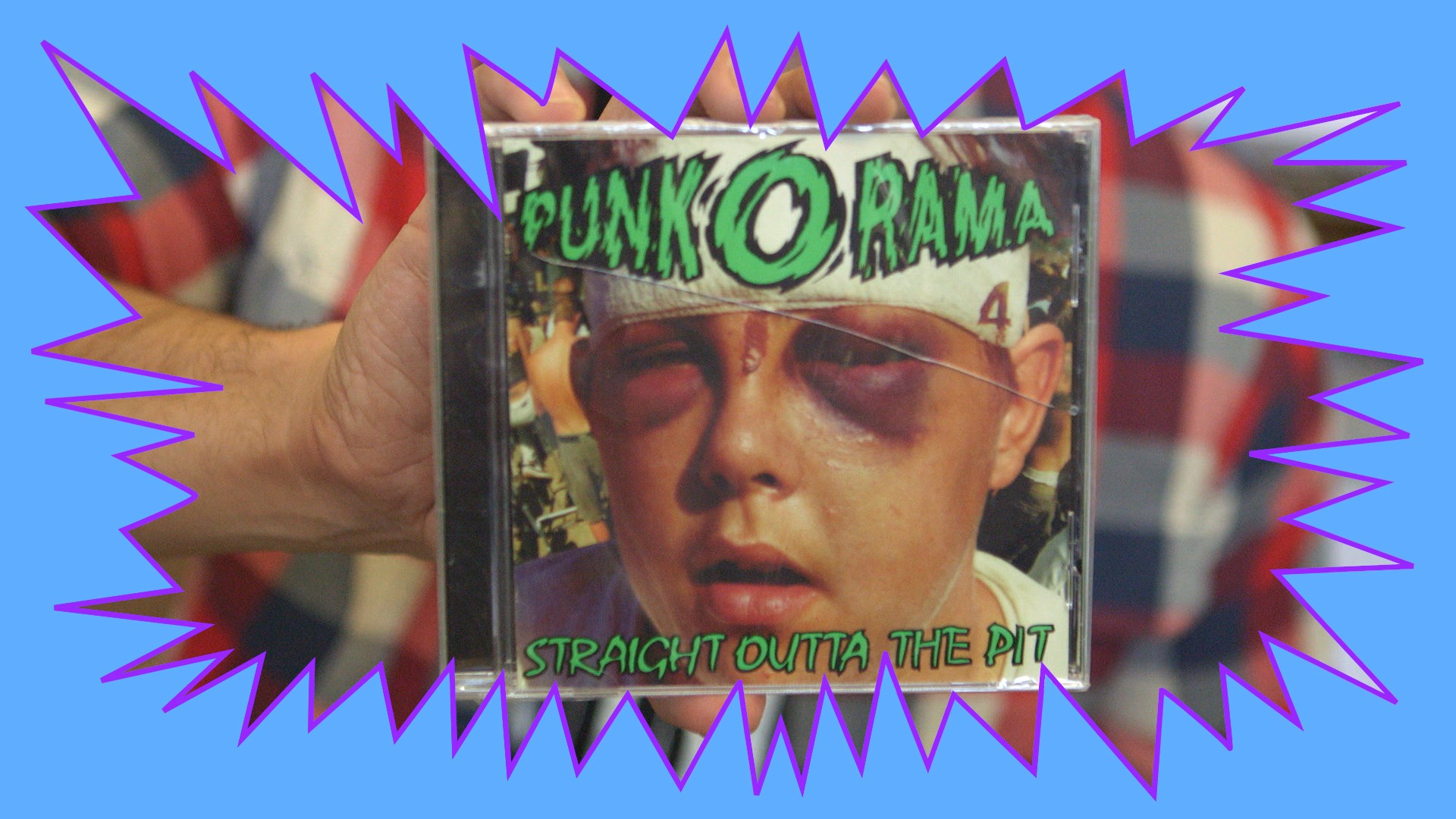

In 1992, Epitaph Records founder Brett Gurewitz released More Songs About Anger, Fear, Sex, and Death, a collection of 26 songs by bands affiliated with his Los Angeles-based label. It was an homage to the 80s punk compilations he grew up on like Hell Comes to Your House. The problem was, the name sucked, and at around $16, it was too expensive for broke punk kids. So, in 1994, he released the pithier-titled Punk-O-Rama. Adorned with an obnoxiously neon-green cover, the CD showcased a dozen of the label’s top acts like Rancid, Pennywise, and Total Chaos. And at only five bucks, the price was right.

Punk-O-Rama, ran from 1994 to 2005 for ten volumes.

Meanwhile, over in San Francisco, NOFX frontman and co-founder of the newly launched label Fat Wreck Chords, “Fat Mike” Burkett, also decided to throw his hat into the compilation ring. That year, his label released Fat Music for Fat People, a 14-track CD featuring Propagandhi, Lagwagon, and Strung Out, among others on his roster, and started giving it away at shows for free.“I shipped a thousand of them to every show NOFX had on tour, and we gave them all away. It was really unheard of because CDs were so expensive back then,” Burkett told us. “People don’t remember, but getting a CD for free was a big fucking deal. It was like someone just gave you $15.”

Fat Music, ran from 1994 to 2015 for eight volumes.

When the tour was over, he started selling them for the low price of $3.98. It wasn’t enough to turn a profit since, at the time, CDs were really expensive to produce, but the branding and promotional value easily made it worthwhile. Fat Music for Fat People ended up selling around 200,000 copies and made Fat Wreck Chords a household name in the genre. Cheap comp CDs soon became young punks’ de facto tool for pre-internet discovery of new artists, offering suburban teens a gateway to the acts on the forefront of a revived genre.

Advertisement

This birthed a bit of healthy rivalry between the two labels. “I know Mike thinks that Fat Music for Fat People came out before Punk-O-Rama but that’s bullshit because my comp came out before that one. And that was just a drop in the bucket in comparison. Those guys were very, very tiny at that time,” says Gurewitz. Fat Wreck Chords began to grow, though, thanks in part to the compilations, and steadily enough that NOFX eventually switched from Epitaph to Fat Wreck Chords for their album releases.Epitaph and Fat began releasing new editions almost every year—each of which featured signature artwork that made them stand out at record store counters—and would usually stick a mail-order catalog inside. The more comps they sold, the more their mail-order increased, driving sales of their bands’ LPs and T-shirts. The CDs became a Warped Tour staple, and other labels started following suit, including Hopeless Records, Nitro Records, Kung Fu Records, Vagrant Records, Hellcat Records (an offshoot of Epitaph), and Go-Kart Records, which released Expose Yourself, the first such compilation to be carried by Hot Topic.“Back then, it was like: You can’t sell to Hot Topic, that’s not punk,” remembers Go-Kart founder, Greg Ross. But he saw the potential selling power of being available in a major chain store and made a deal with the mall retailer. “All of a sudden, all the labels jumped in, all the way up to Sony. They would have five to ten of these cheap-o samplers at any time, right next to the register. And they would account for, in some cases, 60 to 70 percent of your sales on a low-priced sampler. It was insane.”

Advertisement

Go-Kart Vs. the Corporate Giant, ran from 1997 to 2006 for four volumes.

“I remember one year we got it into Blockbuster’s music store, Blockbuster Music, and we convinced them to put the comps on a display,” says Louis Posen, Hopeless Records founder. “I don’t know how we did this, but we had Hopelessly Devoted to You on the counter of a national chain.” It didn’t hurt that these compilations were often wrapped in shiny foil and had Willy Wonka-inspired golden tickets inside, making them irresistible to younger fans with just a few dollars of disposable income.Not only did comps help punk rock infiltrate the malls and chain stores of America, it carved out a self-contained industry for bands whose songs wouldn’t have otherwise landed on Billboard charts. “Bands always have a couple of songs that are standouts, and there really wasn’t an outlet for punk on the radio or television. MTV wasn’t really playing it, even college radio wasn’t really that interested. The internet hadn’t come into its own yet,” says Gurewitz. “And Punk-O-Rama was a way to take the best songs and put them all together. It was a form a communicating, playlisting almost.”“For years after I did these comps, I would run into bands who had broken up and would always get these comments like, ‘Thank you so much. When we would go out and tour, no one would know anything. Then all of a sudden we’d go into the song from your sampler and the crowd would go crazy,’” says Ross.

Hopelessly Devoted to You, ran from 1996 to 2009 for seven volumes.

“Every band had a hit song and every band now has a song that they can never not play,” Burkett laughs. “Not many people bought the Diesel Boy album but everybody knew the ‘pants are falling down’ song. They sold 20,000 records but that comp probably sold 600,000 or 700,000 copies, so more people knew that one song.”

Advertisement

Labels diversified their compilation output, launching several more series, with some aimed at benefitting causes or promoting social change. Hopeless Records launched a non-profit organization, Sub City, and coordinated the Take Action! Tour along with the Take Action! CD compilation series, which ran for 11 volumes. The tour and series helped raise over two and a half million dollars for charity, Posen says, with several hundred thousand dollars coming from the sale of the CDs alone.

Give 'Em the Boot, ran from 1997 to 2009 for seven volumes.

Fat Wreck Chords released the Rock Against Bush series, which, in conjunction with the website Punkvoter, aimed to register young voters and rally support against the re-election of President George W. Bush. The two-volume series featured many previously unreleased songs from dozens of artists.“I got a fucking original, unreleased great Green Day song, I got an unreleased Foo Fighters song, I got all kinds of shit on those things. I just called everyone I knew who was famous in a band,” says Burkett. “I didn't have to twist any arms. There were two bands that said no and everyone else was down. That was Blink [182] and the Vandals. Tom [DeLonge] was a Republican and he didn't want to do it.”After nearly a decade of popularity and millions of copies sold, the compilation bubble burst in the mid 2000s. Music fans were downloading tracks, and CD sales plummeted. The national punk craze had also dwindled, and distance grew between the genre’s sub-mutations, from post-hardcore to emo. Epitaph, which had reaped the highest level of success off the fad—selling more than two million copies in the Punk-O-Rama series—ended the flagship series in 2005 with its tenth edition. “I didn’t want Epitaph to turn into a nostalgia label,” says Gurewitz. “You can’t just stay the same; culture marches on. Trying to keep that 90s skate-punk sound alive forever would just be a pointless exercise.”