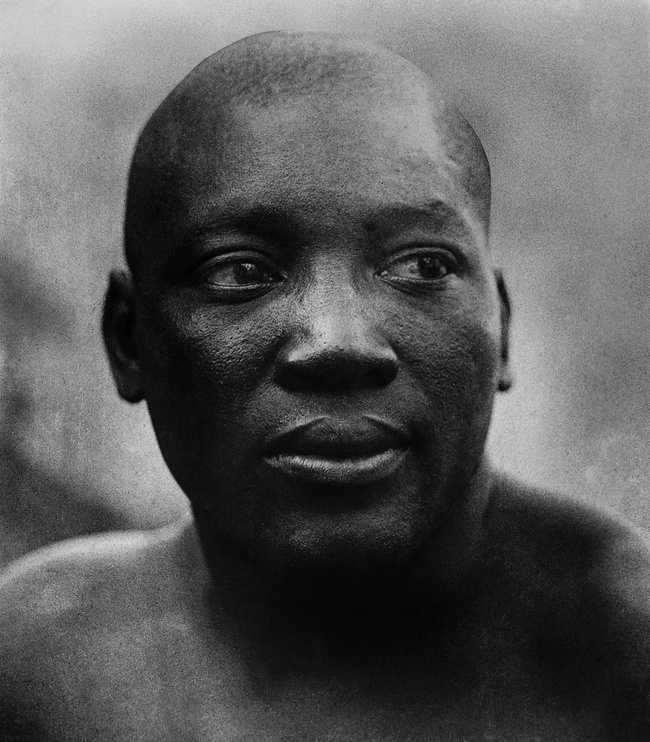

Photo by American Stock/Getty Images

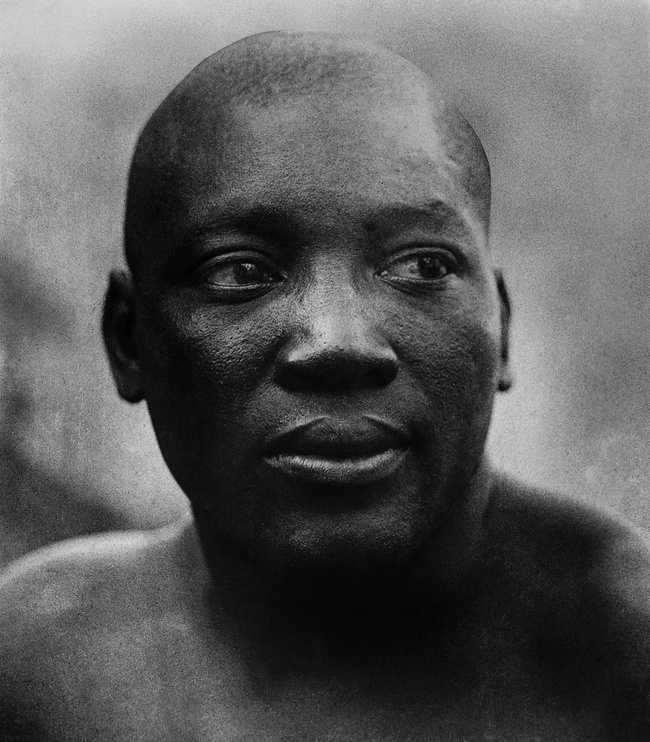

The "talented tenth". That's who W.E.B. Du Bois thought would make the difference for black people of the United States. The success of writers, poets and musicians in the Harlem Renaissance did much to support his theory. Booker T. Washington, meanwhile, was convinced that gradual betterment of circumstance could be achieved through self-improvement and co-operation, and consequently founded the Tuskegee Institute to teach practical skills to African Americans.Boxer Jack Johnson couldn't give a damn for the perception of the black community, he knew exactly what he was, how much he was worth, and how he could prove it. The American dream had been built on the bleeding backs of slave labor, but Johnson—The Galveston Giant—built his own American dream with his wits and with his fists.Simple Beginnings

For all the talk of hunger in the world of fighting, Johnson was not a desperate man. Johnson never suffered because of his race in his hometown of Galveston, Texas, and fell into boxing through his love of fighting and his distaste for any other form of labor. Johnson went through periods of work on docks and in stables, but the only thing he enjoyed (aside from drinking, gambling, and whoring) was fighting.Johnson got his start as a boxer in back alleys and bar rooms, just like any other of the age. He even, reportedly, competed in a battle royale, less of a boxing match and more a fist fight between multiple men in the same ring. These were almost exclusively populated by black boxers desperate to make a quick buck, and occasionally even took place blindfolded. It was the nineteenth century equivalent of midgets Thai boxing. Fighting through the local ranks, Johnson boxed a trilogy against a black fighter named Klondike who had declared himself the black heavyweight champion of the world. After a loss, a draw, and finally a win over Klondike, Johnson met Joe Choynski in his ninth fight. Choynski was a truly talented boxer where Johnson was still finding his feet as a fighter. Accounts differ as to what took place—some say Choynski knocked Johnson out with a left hook to the eye socket, Johnson himself remarks that he had "since learned it was a "right hook". Whatever the case, the smaller, older, savvier boxer put Johnson down for the count.In one of those remarkable twists of fate, the police broke up the fight (conveniently after its conclusion) and the two men were thrown in a jail cell. They were forced room-mates for several weeks, and the Sherriff—who loved the manly art—allowed the local boxing club to send Johnson and Choynski boxing gloves which they could use to playfully spar in the yard.Choynski and Johnson became firm friends and Johnson, who had struggled to find a trainer to take him on, received two weeks of uninterrupted, one-on-one tuition. Choynski's words to Johnson rang true when he declared that "no man who moves like you should ever be getting hit clean".The State of Boxing

Fighting through the local ranks, Johnson boxed a trilogy against a black fighter named Klondike who had declared himself the black heavyweight champion of the world. After a loss, a draw, and finally a win over Klondike, Johnson met Joe Choynski in his ninth fight. Choynski was a truly talented boxer where Johnson was still finding his feet as a fighter. Accounts differ as to what took place—some say Choynski knocked Johnson out with a left hook to the eye socket, Johnson himself remarks that he had "since learned it was a "right hook". Whatever the case, the smaller, older, savvier boxer put Johnson down for the count.In one of those remarkable twists of fate, the police broke up the fight (conveniently after its conclusion) and the two men were thrown in a jail cell. They were forced room-mates for several weeks, and the Sherriff—who loved the manly art—allowed the local boxing club to send Johnson and Choynski boxing gloves which they could use to playfully spar in the yard.Choynski and Johnson became firm friends and Johnson, who had struggled to find a trainer to take him on, received two weeks of uninterrupted, one-on-one tuition. Choynski's words to Johnson rang true when he declared that "no man who moves like you should ever be getting hit clean".The State of Boxing

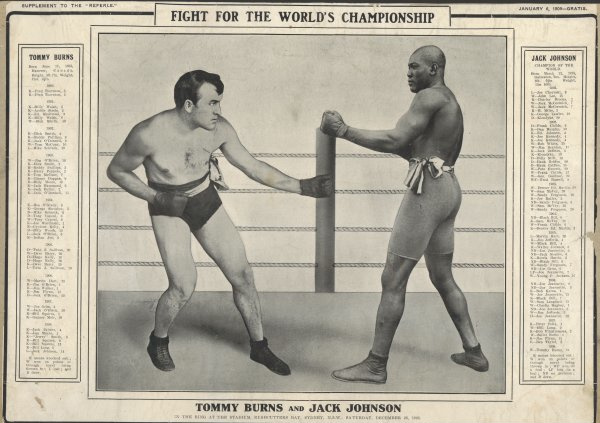

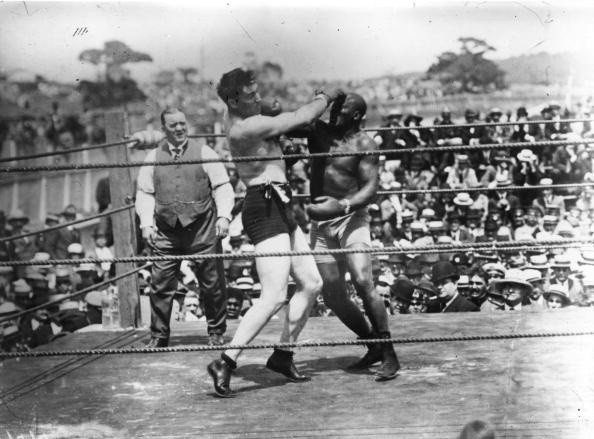

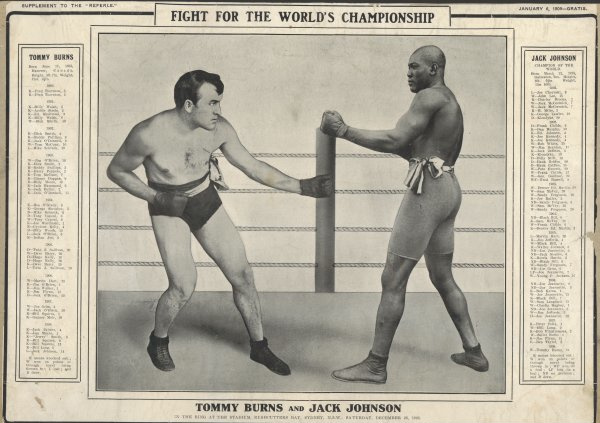

The problem for Johnson was that no heavyweight champion would willingly meet a black opponent. This was actually a fairly recent tradition, Tom Cribb had defended his English title (the world title at that point) against the black challenger, Tom Molineux in 1810. It was John L. Sullivan who drew the color line in front of the world heavyweight title in the 1880s. After winning his title Sullivan retired to the stage for three years citing no worthy challengers left to fight. What he meant was "no worthy challengers except Peter Jackson".Jackson, the Black Prince, was the Australian heavyweight champion and many in the press reckoned that he was the man to give the Great John L. a hard fought contest. Sullivan moved around a good deal on the idea of fighting Jackson, sometimes saying "White men, $10,000. Negroes, double that", but ultimately refused all offers. Jackson died penniless, appearing in productions of Uncle Tom's Cabin to make ends meet as his skills declined.The heavyweight champions who followed—James Corbett, Bob Fitzsimmons, and Jim Jeffries—all held to this tradition of taking on no black challengers, even though they had all fought black boxers before they became world champion.In 1903, Jim Jeffries was king of the heavyweights and the question of a black challenger began to be pushed by the media more and more. But the focus was on The Oxnard Bull, Sam McVey. Here Jeffries used Johnson's success against the idea of the black challenger—noting that since McVey had lost to Johnson, he couldn't be considered for a title shot. And that as Johnson was much smaller than McVey, he also couldn't be considered as a true heavyweight. It was the meandering logic of a racist at its finest.When Johnson and McVey met for a second time, again the papers began to make noise about a possible McVey title shot, but Johnson received no such acclaim. Why? Because he was a boring fighter, plain and simple. Sam McVey and Sam Langford were beloved by the press and by fight fans in spite of their race because they knocked people out. Johnson was a clinch fighter, a defensive artist, and quite often a staller. The second bout with McVey was called "one of the poorest fights this city has ever seen" by the San Francisco Call. The journalist also referred to Johnson as "the colored heavyweight champion, who is dying to fight Jeffries – and probably would if he did".The goalposts kept moving as Johnson continued to beat prospective claimants to a shot at Jeffries' title. At one point Jeffries declared, as Sullivan had said about Jackson, that he would fight Johnson in a locked room for a winner-take-all side bet, but Johnson considered himself well above that kind of tomfoolery.Eventually, Jeffries followed Sullivan's lead and retired from boxing with no challengers remaining—except all the black ones. Marvin Hart and Tommy Burns fought for the vacant title and Burns won it, becoming the first Canadian heavyweight champion in the process. Burns proceeded to take the title on a world tour, from England, to Paris, to Australia, and Johnson followed him every step of the way. It was only once Australian promoter, Hugh D. McIntosh offered Burns the exorbitant amount of $30,000 that Burns agreed to step into the ring with Johnson in Sydney, with the heavyweight title on the line.Johnson had always maintained that the hard part would be getting the champion to agree to fight. The fight itself was seemingly effortless. Burns rushed Johnson at every opportunity, and Johnson went to what is sometimes termed the Johnson clinch. Rather than wrapping one arm under his armpit and the other under his opponents (as is the classical over-under tie up), Johnson would cup his hands and wrists over his opponent's biceps, pinning their arms to their sides as if he had pulled their coat down over them. Pushing and pulling his opponent around, Johnson would allow them to flail away aimlessly.

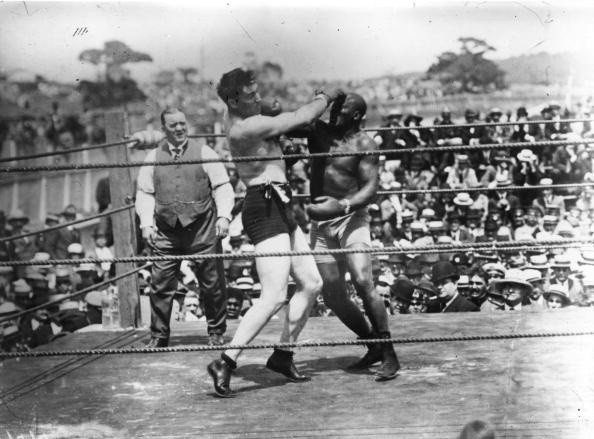

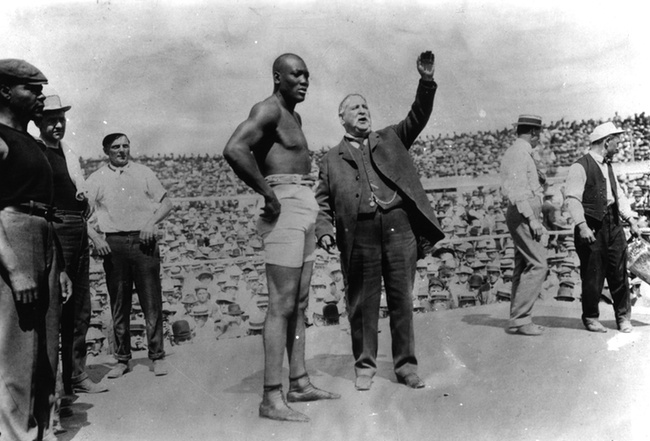

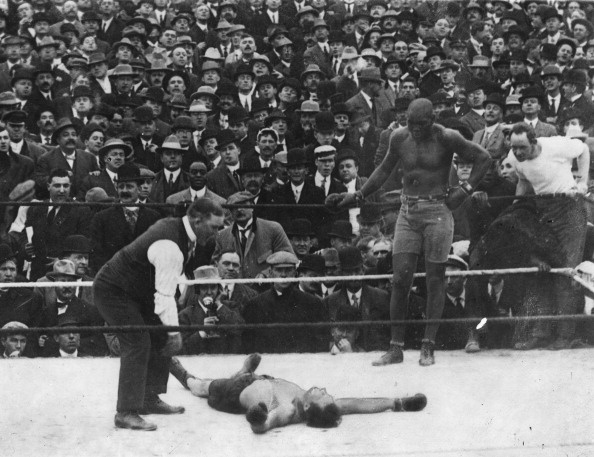

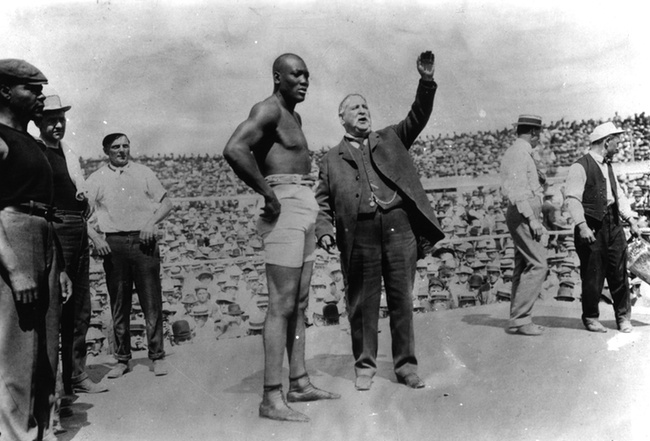

It was only once Australian promoter, Hugh D. McIntosh offered Burns the exorbitant amount of $30,000 that Burns agreed to step into the ring with Johnson in Sydney, with the heavyweight title on the line.Johnson had always maintained that the hard part would be getting the champion to agree to fight. The fight itself was seemingly effortless. Burns rushed Johnson at every opportunity, and Johnson went to what is sometimes termed the Johnson clinch. Rather than wrapping one arm under his armpit and the other under his opponents (as is the classical over-under tie up), Johnson would cup his hands and wrists over his opponent's biceps, pinning their arms to their sides as if he had pulled their coat down over them. Pushing and pulling his opponent around, Johnson would allow them to flail away aimlessly. By the later rounds, Burns was not only exhausted, but humiliated. Johnson rattled Burns with punches out of a clinch and the police at ringside rushed in to stop the contest, saving Burns some face. Burns wasn't truly knocked out, but the title belonged to Johnson. The world had its first black heavyweight champion.

By the later rounds, Burns was not only exhausted, but humiliated. Johnson rattled Burns with punches out of a clinch and the police at ringside rushed in to stop the contest, saving Burns some face. Burns wasn't truly knocked out, but the title belonged to Johnson. The world had its first black heavyweight champion. The Great White Hope

The Great White Hope

So why was the idea of a black heavyweight champion so unthinkable? Joe Gans had become lightweight champion in 1908 and no one batted an eyelid. In fact, The Old Master was beloved for his boxing guile. The black Canadian, George 'Little Chocolate' Dixon had become the bantamweight champion of the world in 1890, opening as an undercard for John L. Sullivan and fans appreciated his boxing prowess too.The heavyweight title was considered the pinnacle of manly achievement. It was absolute. The absolute best fighter in the world was white, and that was what mattered. When Johnson won it, it bestowed the title of "His Fistic Majesty" (as they used to call Sullivan) on a fighter from an inferior race.But what made it worse was Johnson as an individual. Johnson loved fast cars and easy women. He gambled away most of the money he won, and bought lavish furs and outfits which many thought a black man had little business owning. His dalliances with white women were particularly offensive to white spectators. The only thing that Johnson loved more than these vices? Humiliating the white fighters who had denied him a chance before he was heavyweight champion. Johnson's gloating, inviting of blows, and banter with the opposing corner and ringside spectators infuriated the masses. Johnson was never a prolific finisher, and only seemed to do what he needed to in the ring. One newspaper likened him to the horse, Sysonby, "he never broke a record in his life, but he never ran second either."While waltzing in a clinch with Al Kaufman in a heavyweight title defense, Johnson was harangued by a spectator who wanted to know why Johnson wouldn't fight. Johnson leaned over, while still restraining the struggling Kaufman, and replied "why should I fight? I already have your ten dollars!" Johnson was turning the gentlemanly art into a sideshow and it had to be stopped.It is a curious twist that Johnson himself drew the color line in front of the title as well. When the great Sam Langford begged Johnson for a title fight (the two had met numerous times already), Johnson confided that he was sorry but no-one wanted to see two black men fight for the world title. A view that was supported by the papers of the time. The best black heavyweights were in exactly the same position they had been through history after Johnson broke through. In fact Sam Langford and Sam McVey fought each other a total of fifteen times, waiting for a title fight which never came.So the search was on for the Great White Hope. Anyone who could make the weight had gloves strapped on and tried their luck at restoring the honor of the white race. Most of them never made it anywhere close to a fight with Johnson, and those who did were easily handled. Even Stanley Ketchel, a middleweight who had no business in the ring with Johnson, stepped up for a shot at Johnson's title. He ended up losing a few of his teeth in Johnson's glove. It seemed it would be down to Jim Jeffries to return to the ring.

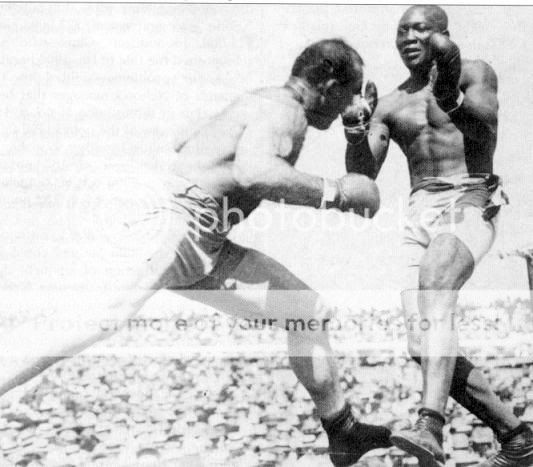

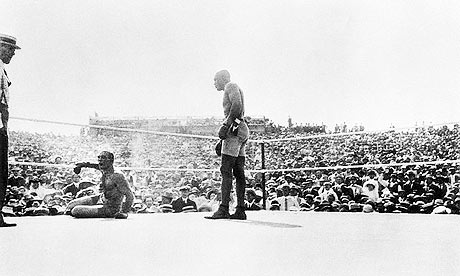

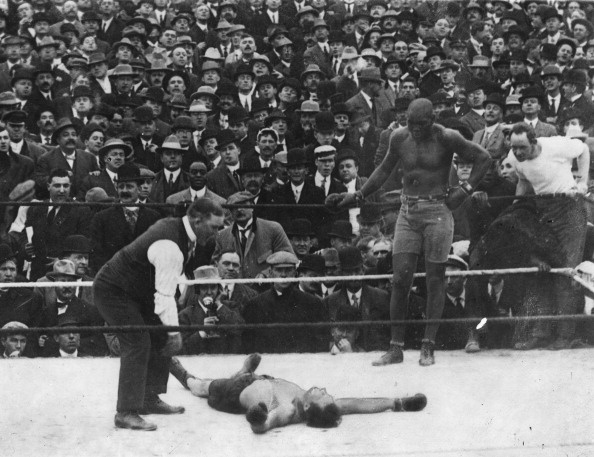

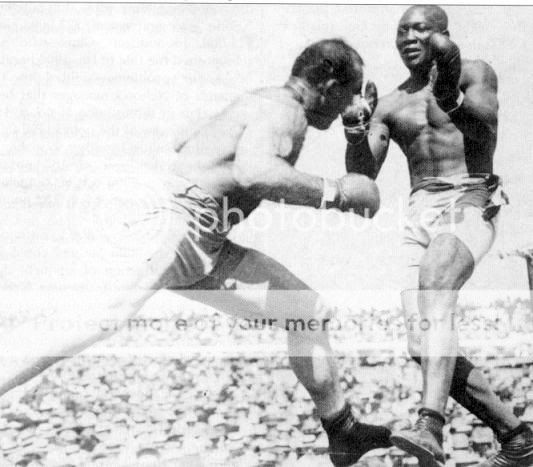

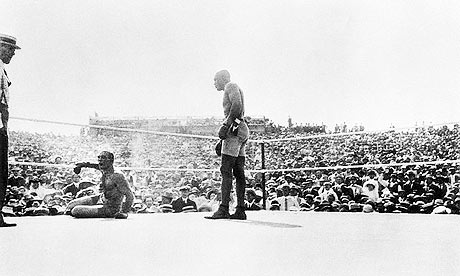

The only thing that Johnson loved more than these vices? Humiliating the white fighters who had denied him a chance before he was heavyweight champion. Johnson's gloating, inviting of blows, and banter with the opposing corner and ringside spectators infuriated the masses. Johnson was never a prolific finisher, and only seemed to do what he needed to in the ring. One newspaper likened him to the horse, Sysonby, "he never broke a record in his life, but he never ran second either."While waltzing in a clinch with Al Kaufman in a heavyweight title defense, Johnson was harangued by a spectator who wanted to know why Johnson wouldn't fight. Johnson leaned over, while still restraining the struggling Kaufman, and replied "why should I fight? I already have your ten dollars!" Johnson was turning the gentlemanly art into a sideshow and it had to be stopped.It is a curious twist that Johnson himself drew the color line in front of the title as well. When the great Sam Langford begged Johnson for a title fight (the two had met numerous times already), Johnson confided that he was sorry but no-one wanted to see two black men fight for the world title. A view that was supported by the papers of the time. The best black heavyweights were in exactly the same position they had been through history after Johnson broke through. In fact Sam Langford and Sam McVey fought each other a total of fifteen times, waiting for a title fight which never came.So the search was on for the Great White Hope. Anyone who could make the weight had gloves strapped on and tried their luck at restoring the honor of the white race. Most of them never made it anywhere close to a fight with Johnson, and those who did were easily handled. Even Stanley Ketchel, a middleweight who had no business in the ring with Johnson, stepped up for a shot at Johnson's title. He ended up losing a few of his teeth in Johnson's glove. It seemed it would be down to Jim Jeffries to return to the ring. Jeffries, The Boilermaker, was a mammoth of a man. Enormously strong and a tremendous hitter, he was never noted for his defense, but he could grind through anyone placed in front of him, doing it to both Bob Fitzsimmons and to James Corbett, twice. The calls on Jeffries to leave the simple, farming life he had set up for himself were louder than ever as Johnson routed Ketchel with ease. Even John L. Sullivan, who had complained publicly that Jeffries had fought nothing but wash ups and patsies, was suddenly in Jeffries corner.Jeffries had the camp of his life as he chiseled himself back into fighting shape under the tuition of former rival, James Corbett and the encouragement of The Great John L., even enlisting the help of the wrestling champions, Farmer Burns and Frank Gotch in order to prepare him for the clinch with Johnson. But it was all for naught.Jimmy Wilde put it best when he said that Johnson wasn't half the man on offence that he could be when his opponent was leading. The more aggressive the opponent, the more furious Johnson's return. Jeffries brought the most aggression and strength of anyone to date, and Johnson destroyed him. Again it was the use of tie ups to tire Jeff out, and the flurries of punches in the later stages of rounds which did the damage.

Jeffries, The Boilermaker, was a mammoth of a man. Enormously strong and a tremendous hitter, he was never noted for his defense, but he could grind through anyone placed in front of him, doing it to both Bob Fitzsimmons and to James Corbett, twice. The calls on Jeffries to leave the simple, farming life he had set up for himself were louder than ever as Johnson routed Ketchel with ease. Even John L. Sullivan, who had complained publicly that Jeffries had fought nothing but wash ups and patsies, was suddenly in Jeffries corner.Jeffries had the camp of his life as he chiseled himself back into fighting shape under the tuition of former rival, James Corbett and the encouragement of The Great John L., even enlisting the help of the wrestling champions, Farmer Burns and Frank Gotch in order to prepare him for the clinch with Johnson. But it was all for naught.Jimmy Wilde put it best when he said that Johnson wasn't half the man on offence that he could be when his opponent was leading. The more aggressive the opponent, the more furious Johnson's return. Jeffries brought the most aggression and strength of anyone to date, and Johnson destroyed him. Again it was the use of tie ups to tire Jeff out, and the flurries of punches in the later stages of rounds which did the damage. On full display was Johnson's legendary uppercut, thrown as he held the opponent away with a cross-face, turning his hips all the way through so that the uppercut was almost being thrown to his side.

On full display was Johnson's legendary uppercut, thrown as he held the opponent away with a cross-face, turning his hips all the way through so that the uppercut was almost being thrown to his side. Following the bout the great Jeffries was forced to admit Johnson's skill and conceded that even in his prime, he couldn't have touched Johnson.

Following the bout the great Jeffries was forced to admit Johnson's skill and conceded that even in his prime, he couldn't have touched Johnson. Johnson summed it up best in his recollections written shortly after the bout:"The last hope of the white race had failed, since that day no other has been found to try to replace him."The Fall of Johnson

Johnson summed it up best in his recollections written shortly after the bout:"The last hope of the white race had failed, since that day no other has been found to try to replace him."The Fall of Johnson

Johnson's title had always protected him. No one would attack or lynch the heavyweight champion of the world. Not out of fear or respect, but out of the belief that a white man would soon show this black man what for.When Jim Jeffries and the Great White Hope proved to be only that that asterisk by Johnson's title disappeared and the public attitude towards Johnson became far less tolerant. Race riots resulted from his drubbing of Jeffries, culminating in a number of deaths. Film of the fight—which had been expensively commissioned—was banned from being shown in most cities. Several white men even committed suicide, with one remarking that "life isn't worth living now that Jeff has lost". So Johnson's brilliance, while caught extensively on film, was censored away.Even Teddy Roosevelt, himself a lover and practitioner of the sweet science, spoke out against fight film being shown and supported the ban. Roosevelt wrote:"The last contest provoked a very unfortunate display of race antagonism… and it would be an admirable thing if some method could be devised to stop the exhibition of the moving pictures taken thereof."Coverage of Johnson in the papers moved from that of a boxing champion to that of a celebrity playboy. Just as we get our daily fix of celebrity gossip and tut disapprovingly, Johnson's life and habits were printed for the world to see each day. Johnson's relationships with white women would prove to be his downfall. His first marriage to Etta Duryea, a wealthy, white divorcee, ended in tragedy. The papers insisted that Duryea took her own life due to the solitary existence she lived while her husband was out philandering. One newspaper recounted Etta's last words as "God have pity on a lonely woman". Another went further and had Johnson's brother, who was working the bar downstairs, starting a sing-along on news of her suicide.It was the eighteen-year-old Lucille Cameron who would ultimately bring down the great champion, though. Working in Johnson's cafe as a waitress, Cameron began to appear publicly on Johnson's arm just a few weeks after the passing of Etta Duryea, causing quite a stir. While the newspapers presented the story as Johnson stealing a naïve teenager from her parents, the truth was that Johnson met Cameron when she was working as a prostitute and decided to take her away from it.It was Cameron whom the police went after, arresting her on trumped up charges of Johnson's cafe being open beyond legal hours. They soon turned her into a witness on a case of "white slavery". As Johnson had paid for her tickets into town, he was charged under the Mann Act, an act which prohibited the transporting of women over state lines for "immoral purposes". While I'm sure we can all imagine Johnson's intentions, they were certainly not criminal and the wording of the law was manipulated to fit.Newspaper coverage turned into a frenzy. Where before just the sporting pages had covered Johnson, he was now plastered across front pages. Richard K. Fox, who was happy enough to make money off of Johnson by writing a biography that Johnson endorsed, suddenly believed that Johnson was "the vilest, most despicable creature that lives". Southern newspapers even called to show Johnson "Southern hospitality".

Johnson's relationships with white women would prove to be his downfall. His first marriage to Etta Duryea, a wealthy, white divorcee, ended in tragedy. The papers insisted that Duryea took her own life due to the solitary existence she lived while her husband was out philandering. One newspaper recounted Etta's last words as "God have pity on a lonely woman". Another went further and had Johnson's brother, who was working the bar downstairs, starting a sing-along on news of her suicide.It was the eighteen-year-old Lucille Cameron who would ultimately bring down the great champion, though. Working in Johnson's cafe as a waitress, Cameron began to appear publicly on Johnson's arm just a few weeks after the passing of Etta Duryea, causing quite a stir. While the newspapers presented the story as Johnson stealing a naïve teenager from her parents, the truth was that Johnson met Cameron when she was working as a prostitute and decided to take her away from it.It was Cameron whom the police went after, arresting her on trumped up charges of Johnson's cafe being open beyond legal hours. They soon turned her into a witness on a case of "white slavery". As Johnson had paid for her tickets into town, he was charged under the Mann Act, an act which prohibited the transporting of women over state lines for "immoral purposes". While I'm sure we can all imagine Johnson's intentions, they were certainly not criminal and the wording of the law was manipulated to fit.Newspaper coverage turned into a frenzy. Where before just the sporting pages had covered Johnson, he was now plastered across front pages. Richard K. Fox, who was happy enough to make money off of Johnson by writing a biography that Johnson endorsed, suddenly believed that Johnson was "the vilest, most despicable creature that lives". Southern newspapers even called to show Johnson "Southern hospitality". Johnson was forced into political exile in France and defended his title three more times before fighting Jess Willard in Cuba, and losing the title to a man who had little to no boxing talent to speak of. Johnson had hit rock bottom.Johnson had done as much damage to his fellow black heavyweights as he had done good. It wasn't until 1937, almost thirty years after Johnson had won the title, that another black man was allowed to challenge for it. When that man, Joe Louis, did put forward a sterling campaign for a title shot, he had a list of dos and don'ts from his handlers which included everything from smiling at white women, or after knocking out and opponent, to publicly eating watermelon.At the time of Louis' rapid rise, he was being handled by Jack Blackburn. Johnson and Blackburn had despised each other for some time, and Johnson went behind Blackburn's back to Louis' financial backers, asking to replace Blackburn as coach. They declined and Johnson instead spent the next few years viciously spreading what he thought to be the key to defeating Louis. It was the lazy way Louis brought his jab back, declared Johnson, a good sway back or retreating shuffle into a right straight and Louis would be done for.When Max Schmeling handed Joe Louis the first defeat of Louis' career, it happened in an eerily similar fashion.

Johnson was forced into political exile in France and defended his title three more times before fighting Jess Willard in Cuba, and losing the title to a man who had little to no boxing talent to speak of. Johnson had hit rock bottom.Johnson had done as much damage to his fellow black heavyweights as he had done good. It wasn't until 1937, almost thirty years after Johnson had won the title, that another black man was allowed to challenge for it. When that man, Joe Louis, did put forward a sterling campaign for a title shot, he had a list of dos and don'ts from his handlers which included everything from smiling at white women, or after knocking out and opponent, to publicly eating watermelon.At the time of Louis' rapid rise, he was being handled by Jack Blackburn. Johnson and Blackburn had despised each other for some time, and Johnson went behind Blackburn's back to Louis' financial backers, asking to replace Blackburn as coach. They declined and Johnson instead spent the next few years viciously spreading what he thought to be the key to defeating Louis. It was the lazy way Louis brought his jab back, declared Johnson, a good sway back or retreating shuffle into a right straight and Louis would be done for.When Max Schmeling handed Joe Louis the first defeat of Louis' career, it happened in an eerily similar fashion. We often over-simplify Johnson's life when we look back, particularly because of his race and the painting of American racism in all places with the same brush. In truth, Johnson was at many points a beloved pugilist. When he stepped into the ring after a Jeffries title defense to publicly call the champion out, Johnson received more applause than Jeffries' knockout win did. When he fought Tommy Burns in Australia, Johnson received more cheers than the champion again. When Jeffries was looking for any excuse not to fight a black man, the newspapers kept Johnson's name front and center after his second win over McVey.It was only once Johnson became the champion that America realized it didn't want him, and his own decisions had a lot to do with that. While today a champion's behavior outside of the ring doesn't concern us, many of the spectators of the time had grown up in the days of John L. Sullivan (who signed off his post fight speeches with "yours, always on the level, John L. Sullivan") and "Gentleman Jim" Corbett. Men who were considered the pinnacle of what it was to be a gentleman and a fighter. The fact that Johnson didn't care what the public at large thought of him, particularly men like Booker T. Washington—whom Johnson believed to not be "altogether frank and honest"—did more to damage Johnson's life than anything he acted out in the ring.Johnson was his own man, and he insisted the world accept him for who he was. He didn't pretend, and in his memoirs this comes through as a refreshing change. It is always dangerous blaming the actions of the victim of racism, because Johnson should have been allowed to be whoever he wanted, but the world wasn't ready for "frank and honest". It wouldn't be for many more decades.

We often over-simplify Johnson's life when we look back, particularly because of his race and the painting of American racism in all places with the same brush. In truth, Johnson was at many points a beloved pugilist. When he stepped into the ring after a Jeffries title defense to publicly call the champion out, Johnson received more applause than Jeffries' knockout win did. When he fought Tommy Burns in Australia, Johnson received more cheers than the champion again. When Jeffries was looking for any excuse not to fight a black man, the newspapers kept Johnson's name front and center after his second win over McVey.It was only once Johnson became the champion that America realized it didn't want him, and his own decisions had a lot to do with that. While today a champion's behavior outside of the ring doesn't concern us, many of the spectators of the time had grown up in the days of John L. Sullivan (who signed off his post fight speeches with "yours, always on the level, John L. Sullivan") and "Gentleman Jim" Corbett. Men who were considered the pinnacle of what it was to be a gentleman and a fighter. The fact that Johnson didn't care what the public at large thought of him, particularly men like Booker T. Washington—whom Johnson believed to not be "altogether frank and honest"—did more to damage Johnson's life than anything he acted out in the ring.Johnson was his own man, and he insisted the world accept him for who he was. He didn't pretend, and in his memoirs this comes through as a refreshing change. It is always dangerous blaming the actions of the victim of racism, because Johnson should have been allowed to be whoever he wanted, but the world wasn't ready for "frank and honest". It wouldn't be for many more decades.

Advertisement

For all the talk of hunger in the world of fighting, Johnson was not a desperate man. Johnson never suffered because of his race in his hometown of Galveston, Texas, and fell into boxing through his love of fighting and his distaste for any other form of labor. Johnson went through periods of work on docks and in stables, but the only thing he enjoyed (aside from drinking, gambling, and whoring) was fighting.Johnson got his start as a boxer in back alleys and bar rooms, just like any other of the age. He even, reportedly, competed in a battle royale, less of a boxing match and more a fist fight between multiple men in the same ring. These were almost exclusively populated by black boxers desperate to make a quick buck, and occasionally even took place blindfolded. It was the nineteenth century equivalent of midgets Thai boxing.

Advertisement

The problem for Johnson was that no heavyweight champion would willingly meet a black opponent. This was actually a fairly recent tradition, Tom Cribb had defended his English title (the world title at that point) against the black challenger, Tom Molineux in 1810. It was John L. Sullivan who drew the color line in front of the world heavyweight title in the 1880s. After winning his title Sullivan retired to the stage for three years citing no worthy challengers left to fight. What he meant was "no worthy challengers except Peter Jackson".Jackson, the Black Prince, was the Australian heavyweight champion and many in the press reckoned that he was the man to give the Great John L. a hard fought contest. Sullivan moved around a good deal on the idea of fighting Jackson, sometimes saying "White men, $10,000. Negroes, double that", but ultimately refused all offers. Jackson died penniless, appearing in productions of Uncle Tom's Cabin to make ends meet as his skills declined.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

So why was the idea of a black heavyweight champion so unthinkable? Joe Gans had become lightweight champion in 1908 and no one batted an eyelid. In fact, The Old Master was beloved for his boxing guile. The black Canadian, George 'Little Chocolate' Dixon had become the bantamweight champion of the world in 1890, opening as an undercard for John L. Sullivan and fans appreciated his boxing prowess too.The heavyweight title was considered the pinnacle of manly achievement. It was absolute. The absolute best fighter in the world was white, and that was what mattered. When Johnson won it, it bestowed the title of "His Fistic Majesty" (as they used to call Sullivan) on a fighter from an inferior race.But what made it worse was Johnson as an individual. Johnson loved fast cars and easy women. He gambled away most of the money he won, and bought lavish furs and outfits which many thought a black man had little business owning. His dalliances with white women were particularly offensive to white spectators.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Johnson's title had always protected him. No one would attack or lynch the heavyweight champion of the world. Not out of fear or respect, but out of the belief that a white man would soon show this black man what for.When Jim Jeffries and the Great White Hope proved to be only that that asterisk by Johnson's title disappeared and the public attitude towards Johnson became far less tolerant. Race riots resulted from his drubbing of Jeffries, culminating in a number of deaths. Film of the fight—which had been expensively commissioned—was banned from being shown in most cities. Several white men even committed suicide, with one remarking that "life isn't worth living now that Jeff has lost". So Johnson's brilliance, while caught extensively on film, was censored away.Even Teddy Roosevelt, himself a lover and practitioner of the sweet science, spoke out against fight film being shown and supported the ban. Roosevelt wrote:"The last contest provoked a very unfortunate display of race antagonism… and it would be an admirable thing if some method could be devised to stop the exhibition of the moving pictures taken thereof."

Advertisement

Advertisement