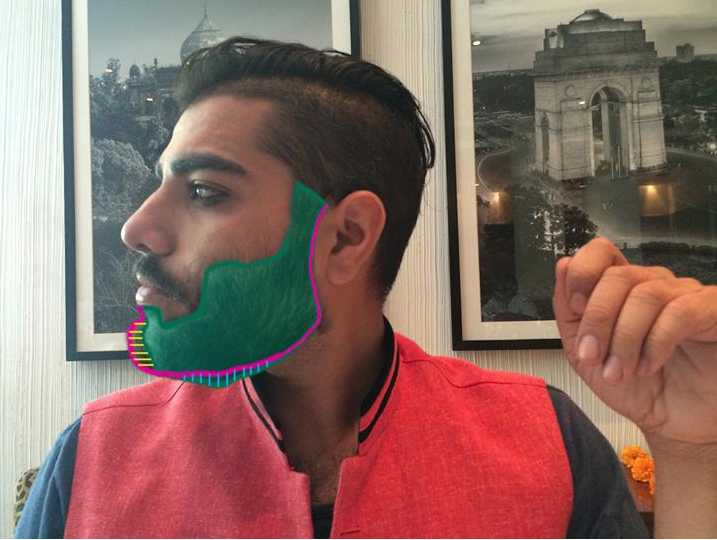

Photo courtesy of the artistIt’s a shit-ass cold day in New York, and Himanshu Suri, better known as Heems, just finished clearing his parents’ driveway with his snow blower. “That was one of the things I bought with my rap money,” he tells me over the phone as we discuss Eat Pray Thug. Even though the subject we’re talking about might seem like the beginning of a new part in his career—EPT is technically his first proper solo album—Heems repeatedly references rap as something from his past. At one point, the Queens native directly says, “I don’t know if I’m gonna be working on music after this album.”Regardless however many pieces of winter weather machinery it might afford him, the fact remains that these days, Heems has mixed feelings about rap as a vocation. He’s not the easiest guy in the world to talk to, either. Heems and I have probably spoken half a dozen times in the past few years. It’s always been friendly, but once it’s time for me to interview him something changes. He’s more guarded, pedantic at times, steering the conversation in whichever way he sees fit. I get the sense that in a way, these are tactics of rhetorical misdirection that he’s had to spend most of his life explaining himself and now that he’s within spitting distance of his 30th birthday, he’s growing tired of it.Though he once had a reputation as a party-starter and a wiseass with Das Racist, his original rap group with the MC Viktor Vazquez (Kool A.D.) and the hype man Ashok Kondabolu (Dapwell), slowly but surely, Suri is getting his shit together. “I spent a lot of last year like, getting back to my roots, getting back to what’s important, getting back to my community, getting back to my family,” he says. The majority of Eat Pray Thug was recorded in 2013 in India, and after years of living off various hustles (most rap-related), he’s got the day job, and he moved back in with his parents, whose Long Island house he helped purchase with yet more rap money.It is because of this air of premature weariness that Heems seems to carry on his shoulders that I truly believe that Eat Pray Thug, great album that it is, might indeed be the last one he ever makes. It’s not a record that everyone is going to like, especially if you gravitated towards his previous group, Das Racist, because of their zaniness and not the complex statements about race and class embedded within the jokes. Instead, it’s a New York album in the same way that Talking Heads, Camu Tao, and Beastie Boys made New York albums: products of an elaborate cultural milieu, collages of high and low art held together with toothpicks and bubblegum, and anchored by voices so unconventional that they can’t help but win you over. That the record is about 9/11—even when it’s not—only adds to this.Continued below.From his reticence with me over the phone, I get the sense that Heems understands some people will not react to it in the way he hopes. Just like clockwork, on the day of its release Pitchfork (early DR boosters) ran a review of Eat Pray Thug that was fair but ultimately negative. Heems took to Twitter to respond to the (white) writer, “the record isn’t made for you so all good.”Besides, Suri doesn’t need rap. He’s got other shit to deal with: namely, his job, which is a new development, one that he’s pleased with. A while back, Suri tells me he asked himself, “What are the brightest minds of my generation are doing? A lot of them are involved in start-ups.” So, he got himself a gig at his friend’s tech company, and now works nine to five.He tells me, “I’m literally juggling a day job, I’m curating an art show, showing artwork in that art show, I’m directing a music video this weekend, doing press, writing treatments for the other videos, I’m working out a marketing plan with my label, and I’m trying to focus on myself.”/ / / Self-portrait via Suri's art exhibit at Aicon GalleryRaised in a working-class family in Queens, New York, Heems attended the prestigious liberal arts college Wesleyan University, and later found work in finance as a headhunter on Wall Street. “Everyone I grew up with in my community is a lawyer or a pharmacist or an engineer, or they messed their lives up in high school by being idiots,” he says. He found himself in the position of “professional rapper” almost by accident, when the song “Combination Pizza Hut and Taco Bell” by Das Racist became a viral hit. It is a song about two dudes (Suri and Vazquez) who were at a combination Pizza Hut and Taco Bell. Depending on whom you asked, it was either a commentary on the pointlessness of big box consumer culture, or it was just pointless.In the span of less than a year, Das Racist released two mixtapes that saw them go from an internet joke to the guys who helped redefine the term “indie rap.” Where the term had once described rap released on independent labels and consumed by discerning hip-hop fans of all stripes, Das Racist made their name because they appealed literally to indie kids: they sourced beats with such indie staples as Diplo and Chairlift, shouted out Tanlines (inventors of the “;(“ emoticon), sampled The Very Best and Nujabes’ theme for the cult anime series Samurai Champloo, and titled songs things like “Coochie Dip City” and “Deep Ass Shit (You’ll Get It When You’re High).” Meanwhile, they were covered extensively by alt-slanted publications such as Pitchfork, The Village Voice, and VICE (the first video feature Noisey ever released, in fact, was on a Das Racist show in Seattle). “We still talked about the things I wanted to talk about, but to a certain extent we hid behind humor,” he says, continuing, “I wanted to talk about my experience in a medium where I wasn’t performing race or performing being working class for everybody who wasn’t. Hip-hop was a working class medium. Ironically, my audience wasn’t very working class at all.”Soon enough, things went sour for the group. Relax, their proper debut, was a critical and commercial disappointment, and the rigors of touring (in 2011, DR performed more than 150 shows, according to Forbes) took a toll on the band. “We were better friends when we started,” Suri told Self-Titled Mag for a 2012 cover story, continuing, “We lived together, worked together, and toured together. You need space after that, with anyone. I wish it didn’t take a toll on that side of things.” As 2012 drew to a close, the band imploded. In December of 2012, Heems let it slip at a gig in Munich that the group had disbanded./ / /Following the dissolution of Das Racist, Heems, who had released two sprawling mixtapes, Nehru Jackets and Wild Water Kingdom, following Relax, fell into something of a black hole. He went through a breakup and fell into a depression, which he combatted, in part, through self-medication. Lines such as, “The great gats be that Tec-9 and that AK, cut lines of yay-yay on that big book from AA” (“Hubba, Hubba”) and, “You addicted to the H-Man, I’m addicted to the H, man” (“Home” feat. Dev Hynes) pepper the record. “That’s what this album is all about—being honest and being vulnerable, and putting it all out there,” he tells me. However, when I ask Heems to discuss the substance abuse he broaches on the record, he politely declines.Besides, Eat Pray Thug is, over everything, an album about 9/11, even when it’s not. Lyrics such as, “And then the towers hit the planes / and I’ll never be the same” (“Flag Shopping”) function in part to explain the devastating effects 9/11 had on minority communities, as well as the devastating effects that 9/11 had on Heems personally. “I was so close to it, close enough to see people jump out of buildings,” he tells me. A source, however subtle, of Suri’s failed interpersonal relationships and substance issues can be traced back to 9/11, a phenomenon Heems repeatedly describes to me as “geopolitical heartbreak.” He says, “I was able to be honest and write songs about what I was going through instead of hiding behind jokes, which were a coping mechanism I had internalized to deal with very painful things like racism and xenophobia.”Instead, Heems deals openly with racism and xenophobia here. “Flag Shopping” is about the sudden panic brown communities were sent into following a surge of post 9/11 racism. “Al Q8a” plays with New York rap’s fascination with the Middle East, reclaiming Dipset’s use of the term “Taliban” and French Montana’s line, “Hi haters, our guns from Al Queda,” as Heems rails against government drones and reminding the listener that he raps “for the Arabs in bodegas toting steel under the registers.”

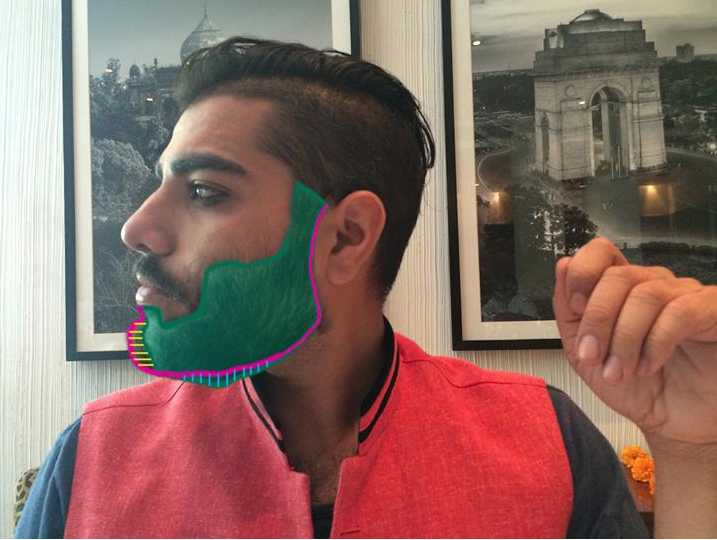

Self-portrait via Suri's art exhibit at Aicon GalleryRaised in a working-class family in Queens, New York, Heems attended the prestigious liberal arts college Wesleyan University, and later found work in finance as a headhunter on Wall Street. “Everyone I grew up with in my community is a lawyer or a pharmacist or an engineer, or they messed their lives up in high school by being idiots,” he says. He found himself in the position of “professional rapper” almost by accident, when the song “Combination Pizza Hut and Taco Bell” by Das Racist became a viral hit. It is a song about two dudes (Suri and Vazquez) who were at a combination Pizza Hut and Taco Bell. Depending on whom you asked, it was either a commentary on the pointlessness of big box consumer culture, or it was just pointless.In the span of less than a year, Das Racist released two mixtapes that saw them go from an internet joke to the guys who helped redefine the term “indie rap.” Where the term had once described rap released on independent labels and consumed by discerning hip-hop fans of all stripes, Das Racist made their name because they appealed literally to indie kids: they sourced beats with such indie staples as Diplo and Chairlift, shouted out Tanlines (inventors of the “;(“ emoticon), sampled The Very Best and Nujabes’ theme for the cult anime series Samurai Champloo, and titled songs things like “Coochie Dip City” and “Deep Ass Shit (You’ll Get It When You’re High).” Meanwhile, they were covered extensively by alt-slanted publications such as Pitchfork, The Village Voice, and VICE (the first video feature Noisey ever released, in fact, was on a Das Racist show in Seattle). “We still talked about the things I wanted to talk about, but to a certain extent we hid behind humor,” he says, continuing, “I wanted to talk about my experience in a medium where I wasn’t performing race or performing being working class for everybody who wasn’t. Hip-hop was a working class medium. Ironically, my audience wasn’t very working class at all.”Soon enough, things went sour for the group. Relax, their proper debut, was a critical and commercial disappointment, and the rigors of touring (in 2011, DR performed more than 150 shows, according to Forbes) took a toll on the band. “We were better friends when we started,” Suri told Self-Titled Mag for a 2012 cover story, continuing, “We lived together, worked together, and toured together. You need space after that, with anyone. I wish it didn’t take a toll on that side of things.” As 2012 drew to a close, the band imploded. In December of 2012, Heems let it slip at a gig in Munich that the group had disbanded./ / /Following the dissolution of Das Racist, Heems, who had released two sprawling mixtapes, Nehru Jackets and Wild Water Kingdom, following Relax, fell into something of a black hole. He went through a breakup and fell into a depression, which he combatted, in part, through self-medication. Lines such as, “The great gats be that Tec-9 and that AK, cut lines of yay-yay on that big book from AA” (“Hubba, Hubba”) and, “You addicted to the H-Man, I’m addicted to the H, man” (“Home” feat. Dev Hynes) pepper the record. “That’s what this album is all about—being honest and being vulnerable, and putting it all out there,” he tells me. However, when I ask Heems to discuss the substance abuse he broaches on the record, he politely declines.Besides, Eat Pray Thug is, over everything, an album about 9/11, even when it’s not. Lyrics such as, “And then the towers hit the planes / and I’ll never be the same” (“Flag Shopping”) function in part to explain the devastating effects 9/11 had on minority communities, as well as the devastating effects that 9/11 had on Heems personally. “I was so close to it, close enough to see people jump out of buildings,” he tells me. A source, however subtle, of Suri’s failed interpersonal relationships and substance issues can be traced back to 9/11, a phenomenon Heems repeatedly describes to me as “geopolitical heartbreak.” He says, “I was able to be honest and write songs about what I was going through instead of hiding behind jokes, which were a coping mechanism I had internalized to deal with very painful things like racism and xenophobia.”Instead, Heems deals openly with racism and xenophobia here. “Flag Shopping” is about the sudden panic brown communities were sent into following a surge of post 9/11 racism. “Al Q8a” plays with New York rap’s fascination with the Middle East, reclaiming Dipset’s use of the term “Taliban” and French Montana’s line, “Hi haters, our guns from Al Queda,” as Heems rails against government drones and reminding the listener that he raps “for the Arabs in bodegas toting steel under the registers.” Photo courtesy the artistAnd then there is “Patriot Act,” which, if Suri’s threat that Eat Pray Thug is indeed his last album, may be the final song the world hears from him. The last song on the record, it’s Heems’ plainest declaration of post-9/11 paranoia yet. Unlike “Combination Pizza Hut and Taco Bell,” the track leaves no room for interpretation. After 90 seconds of spacey, paranoid raps, Heems speaks, plainly and with a tinge of sadness, of the world that he found himself in as a young man:Then the towers fell in front of my eyes. I remember the principal said that they wouldn’t. And for a month, they used my high school as a triage. So we went to school in Brooklyn; the city’s Board of Ed hired shrinks for the students, and maybe I should have seen one. From then on they called us all Osama. The old Sikh men on the bus were Osama. I was Osama. We were Osama. Are you Osama?Maybe Eat Pray Thug is important to Heems because it represents the closure of an arc, the actualization of a rap career. Though Suri might have been labeled “joke rap” in the beginning, he was, all along, trying to explain to us that there was no such thing. He made raps with jokes in them, sure, but the intent behind them was dead serious. And at the end of Eat Pray Thug, Heems made damn sure no one would be laughing. And that just might be the point.He is, it seems, happy with himself, no matter what happens from here. “I mean, look,” he tells me, “I’ve done enough cool shit in my life where I don’t need to worry about whether people think I’m cool or not.”Drew Millard is an associate editor at VICE. Follow him on Twitter.

Photo courtesy the artistAnd then there is “Patriot Act,” which, if Suri’s threat that Eat Pray Thug is indeed his last album, may be the final song the world hears from him. The last song on the record, it’s Heems’ plainest declaration of post-9/11 paranoia yet. Unlike “Combination Pizza Hut and Taco Bell,” the track leaves no room for interpretation. After 90 seconds of spacey, paranoid raps, Heems speaks, plainly and with a tinge of sadness, of the world that he found himself in as a young man:Then the towers fell in front of my eyes. I remember the principal said that they wouldn’t. And for a month, they used my high school as a triage. So we went to school in Brooklyn; the city’s Board of Ed hired shrinks for the students, and maybe I should have seen one. From then on they called us all Osama. The old Sikh men on the bus were Osama. I was Osama. We were Osama. Are you Osama?Maybe Eat Pray Thug is important to Heems because it represents the closure of an arc, the actualization of a rap career. Though Suri might have been labeled “joke rap” in the beginning, he was, all along, trying to explain to us that there was no such thing. He made raps with jokes in them, sure, but the intent behind them was dead serious. And at the end of Eat Pray Thug, Heems made damn sure no one would be laughing. And that just might be the point.He is, it seems, happy with himself, no matter what happens from here. “I mean, look,” he tells me, “I’ve done enough cool shit in my life where I don’t need to worry about whether people think I’m cool or not.”Drew Millard is an associate editor at VICE. Follow him on Twitter.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement