Archbishop Franzo Wayne King licks his lips and silently fingers a few dull brass keys as Sister Wanika King-Stephens calls for the congregation to rise. Clergy outnumber us two-to-one. King closes his eyes and rings out the first brisk notes of “Acknowledgement”, and with that the room falls silent and tunes into a reverent wake up; The Saint John Will-I-Am Coltrane African Orthodox Church is now in session. Behind the archbishop, 11-year-old Karl Nueckel lightly rolls on the cymbals, leaning in close to the shivering bronze, building the noise to intro the bass. Karl is truly superb; skillfully matching King’s old-age, age-old downbeat rhythm, succeeding Elvin Jones’s classic syncopation as they both close their eyes and fifty years of liquid jazz pours out of Nueckel and King in consummate harmony. With Reverend Deacon Max Hoff on the keys and Sister King-Stephens on the bass, a few of the other members produce tambourines, and the room starts to jingle. Mother Marina King begins a low murmur, “a love supreme,” and the choir echoes her, “a love supreme,” the couple behind me hums the notes, “a love supreme,” and the air reverberates, “a love supreme.” I feel it in my throat and in my head, “a love supreme.” Mother Marina begins the opening prayer; “Cleanse us oh Lord and keep us undefiled that we may be numbered among those blessed ones”, the Sisters of Compassion follow, and the room undulates, “a love supreme.” What had brought me here: a jazz-loving cutie, friend of a friend, pointed it out on the 22 through the open sliding window, while idling on Eddy. We could hear the sax out the door, and she asked me if I knew who John Coltrane was.I began to understand what the Archbishop meant when he described Coltrane’s music as the presence of the Holy Spirit; instruments and voices blended into a singular spiritual tonality. The beat picks up and Karl stares straight ahead pounding out the complicated irregular rhythm, holding it steady and open for the Archbishop who jerks forward with each emphatic staccato, bits of spit flying from the corners of his mouth, the Sisters lean and sway as they follow Mother’s call and respond to the gospel. Behind them looms the portrait of either Black Jesus or the Patron Saint John Coltrane sitting on a throne, Book of Revelations in his outstretched hand, “I am Alpha and Omega, the beginning and the ending”. Depictions of Coltrane number the small room, dominating it with his presence. There are a few Byzantine style likenesses of the Saint holding a saxophone, flames bursting from the bell, a few more contemporary drawings and silhouettes hang from banners along the ceiling and against the wall; Coltrane’s eyes strained shut, lips pursed. The room is crowded with these images, not much larger than my kitchen, with space for maybe thirty or so scratchy green armless chairs. I look at the Archbishop and he is sweating. The sound fades out as it started, with a roll on the cymbals, Karl’s face inches away from the vibrating metal, the 68-year-old Archbishop grips his sax tightly and lurches forward, his face contorted into a final bellow. There may as well have been ten thousand in the room to applaud, but he glances upwards, and you can see his redemption in the eyes of God and Trane.

What had brought me here: a jazz-loving cutie, friend of a friend, pointed it out on the 22 through the open sliding window, while idling on Eddy. We could hear the sax out the door, and she asked me if I knew who John Coltrane was.I began to understand what the Archbishop meant when he described Coltrane’s music as the presence of the Holy Spirit; instruments and voices blended into a singular spiritual tonality. The beat picks up and Karl stares straight ahead pounding out the complicated irregular rhythm, holding it steady and open for the Archbishop who jerks forward with each emphatic staccato, bits of spit flying from the corners of his mouth, the Sisters lean and sway as they follow Mother’s call and respond to the gospel. Behind them looms the portrait of either Black Jesus or the Patron Saint John Coltrane sitting on a throne, Book of Revelations in his outstretched hand, “I am Alpha and Omega, the beginning and the ending”. Depictions of Coltrane number the small room, dominating it with his presence. There are a few Byzantine style likenesses of the Saint holding a saxophone, flames bursting from the bell, a few more contemporary drawings and silhouettes hang from banners along the ceiling and against the wall; Coltrane’s eyes strained shut, lips pursed. The room is crowded with these images, not much larger than my kitchen, with space for maybe thirty or so scratchy green armless chairs. I look at the Archbishop and he is sweating. The sound fades out as it started, with a roll on the cymbals, Karl’s face inches away from the vibrating metal, the 68-year-old Archbishop grips his sax tightly and lurches forward, his face contorted into a final bellow. There may as well have been ten thousand in the room to applaud, but he glances upwards, and you can see his redemption in the eyes of God and Trane. In the late 50s, after a near heroin overdose following his forced departure from the Miles Davis Quintet, jazz legend John Coltrane spent seven years writing a personal testament to God, “A Love Supreme”, who’s liner notes begin, “DEAR LISTENER: ALL PRAISE BE TO GOD TO WHOM ALL PRAISE IS DUE”. In the mid-60s, during his experiments with LSD, Coltrane played a show at the Jazz Workshop in San Francisco, where in the audience were the eventual founders of the Church of Saint John Will-I-Am Coltrane: Franzo King and his girlfriend Marina. Franzo described the experience as a “sound baptism”, and Coltrane as more than a musician; a saint chosen to “guide souls back to God.” Since 1971 the couple has been celebrating the music of John Coltrane; highlighting the religious overtones as intended in his original notations and published works; combining hymns, scripture, and the San Francisco community. Their location has changed several times in the last 40 years, but their message has not: “To know sound as the preexisting wisdom of God, and to understand the divine nature of our patron saint in terms of his ascension as a high soul into one-ness with God through sound. In our praises we too seek such a relationship with God. All praise to God. One Mind, A Love Supreme.” - Archbishop Franzo Wayne King D.D.

During the Introit to “Lonnie’s Lament”, a group of Russian tourists came in and sat down behind me. They started speaking rapidly in hushed tones. I tried to focus on keeping time with a tambourine which one of the Sisters of Compassion had given me, but I could distinctly make out an argument in Russian about “black Jesus.” “No,” said one of them, “Louis Armstrong!” and they all stifled laughter. One of the only other attendees, a regular in tattered plaid with a huge unkempt white beard. He’d pull out a recorder, the plastic kind they handed out in school, and softly play along before returning it to a worn pouch, again and again. I tried to follow the words, but it was hard enough to keep a jangly rhythm, so I just said “amen” when they said “amen” and “hallelujah” when they said “hallelujah”.The next bit was The Lord’s Prayer over “Spiritual,” and as King began to play the lingering notes, the Russians got up to leave, but not before pulling aside one of the Sisters to haggle over the price of a T-shirt, all the way through “Glory be to God on high and on earth peace goodwill to men” before giving up and walking out. An incoming regular held the door for them, singing “Praise be to God” over and over. He stood in the back and irregularly stamped his feet, clapped, and shook his head. It was clear that the community was quite small, and for the next hour people filtered in and out, each time a tourist or passerby pressed their face against the glass outside, one of the Sisters would open the door and invite them in, and by the end of the second hour there were maybe ten people scattered in the fuzzy green chairs. A collections plate made its rounds and the homeless guy next to me reached into the pocket of his stretched wool cardigan and dropped in a handful of coins. The music began to cool off and Reverend Sister Wanika King stepped up to the pulpit and began a reading. This was the first time in nearly two hours that the church ensemble: Ohnedaruth, could take a break, and I looked over at the Archbishop who was sitting in the corner wiping the sweat from his brow. He caught my eye and smiled.

In the late 50s, after a near heroin overdose following his forced departure from the Miles Davis Quintet, jazz legend John Coltrane spent seven years writing a personal testament to God, “A Love Supreme”, who’s liner notes begin, “DEAR LISTENER: ALL PRAISE BE TO GOD TO WHOM ALL PRAISE IS DUE”. In the mid-60s, during his experiments with LSD, Coltrane played a show at the Jazz Workshop in San Francisco, where in the audience were the eventual founders of the Church of Saint John Will-I-Am Coltrane: Franzo King and his girlfriend Marina. Franzo described the experience as a “sound baptism”, and Coltrane as more than a musician; a saint chosen to “guide souls back to God.” Since 1971 the couple has been celebrating the music of John Coltrane; highlighting the religious overtones as intended in his original notations and published works; combining hymns, scripture, and the San Francisco community. Their location has changed several times in the last 40 years, but their message has not: “To know sound as the preexisting wisdom of God, and to understand the divine nature of our patron saint in terms of his ascension as a high soul into one-ness with God through sound. In our praises we too seek such a relationship with God. All praise to God. One Mind, A Love Supreme.” - Archbishop Franzo Wayne King D.D.

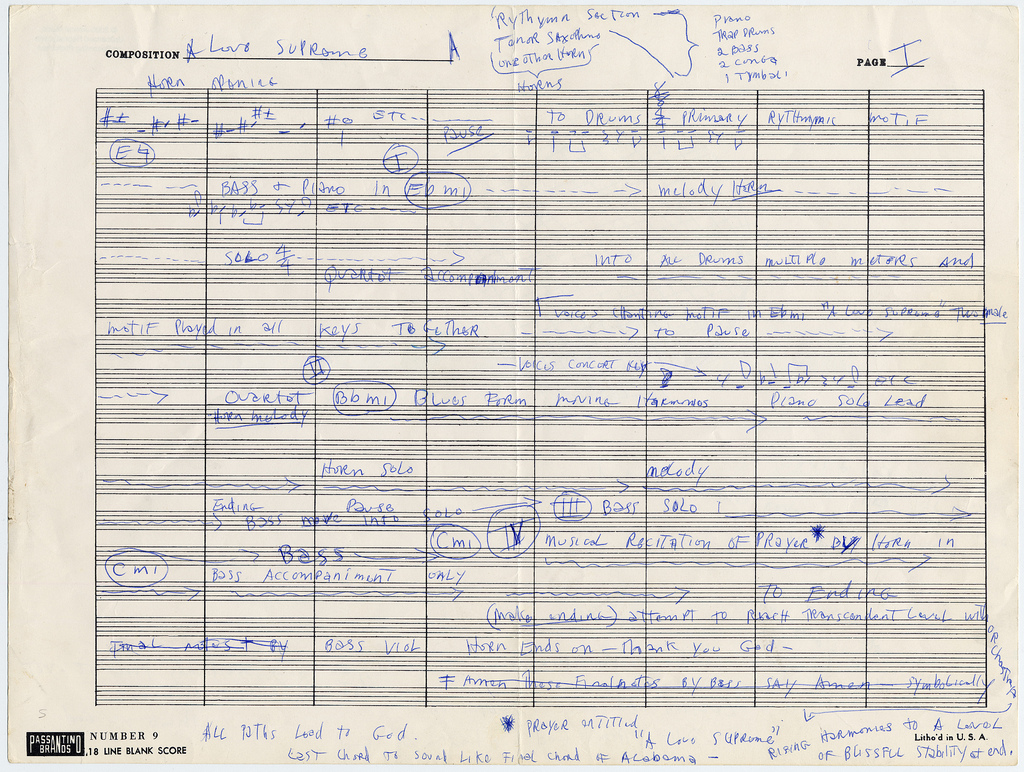

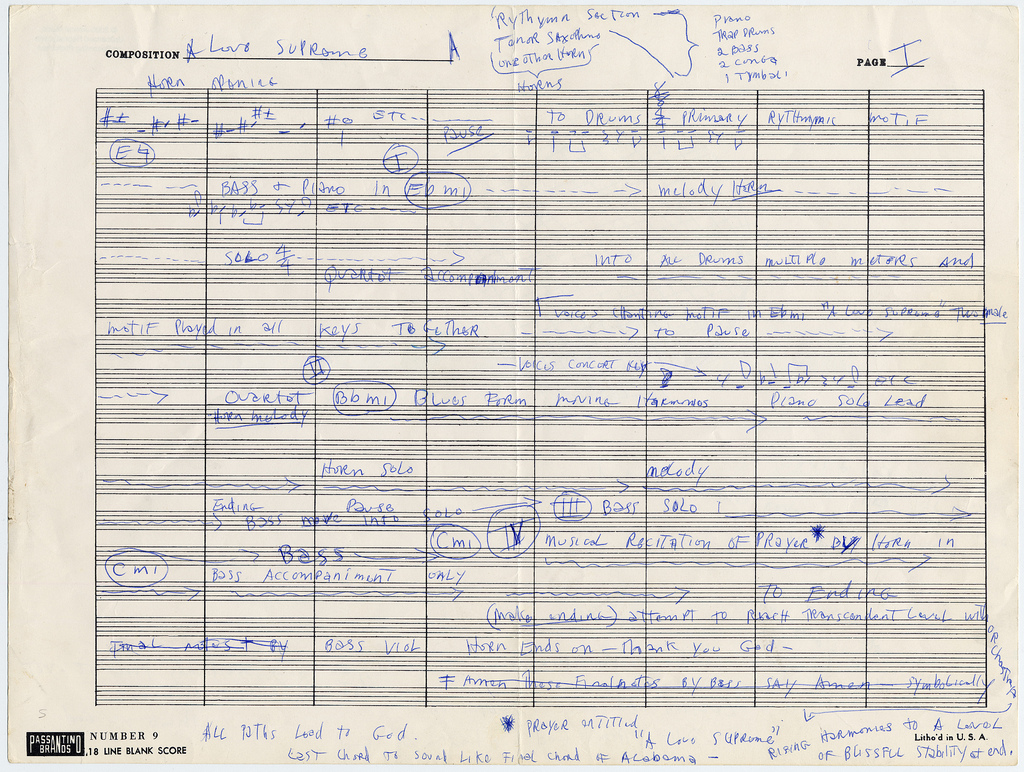

During the Introit to “Lonnie’s Lament”, a group of Russian tourists came in and sat down behind me. They started speaking rapidly in hushed tones. I tried to focus on keeping time with a tambourine which one of the Sisters of Compassion had given me, but I could distinctly make out an argument in Russian about “black Jesus.” “No,” said one of them, “Louis Armstrong!” and they all stifled laughter. One of the only other attendees, a regular in tattered plaid with a huge unkempt white beard. He’d pull out a recorder, the plastic kind they handed out in school, and softly play along before returning it to a worn pouch, again and again. I tried to follow the words, but it was hard enough to keep a jangly rhythm, so I just said “amen” when they said “amen” and “hallelujah” when they said “hallelujah”.The next bit was The Lord’s Prayer over “Spiritual,” and as King began to play the lingering notes, the Russians got up to leave, but not before pulling aside one of the Sisters to haggle over the price of a T-shirt, all the way through “Glory be to God on high and on earth peace goodwill to men” before giving up and walking out. An incoming regular held the door for them, singing “Praise be to God” over and over. He stood in the back and irregularly stamped his feet, clapped, and shook his head. It was clear that the community was quite small, and for the next hour people filtered in and out, each time a tourist or passerby pressed their face against the glass outside, one of the Sisters would open the door and invite them in, and by the end of the second hour there were maybe ten people scattered in the fuzzy green chairs. A collections plate made its rounds and the homeless guy next to me reached into the pocket of his stretched wool cardigan and dropped in a handful of coins. The music began to cool off and Reverend Sister Wanika King stepped up to the pulpit and began a reading. This was the first time in nearly two hours that the church ensemble: Ohnedaruth, could take a break, and I looked over at the Archbishop who was sitting in the corner wiping the sweat from his brow. He caught my eye and smiled. The reading was about coming closer to God through self-improvement and avoiding manifest corruption though words and action. She spoke about Coltrane’s handwritten outline of "A Love Supreme," where he had written a “musical recitation of prayer by horn,” and an “attempt to reach transcendent level with orchestra rising harmonies to a level of blissful stability at the end”. Sister King said that “although our faith has been tested by some who might not take us seriously, it should please us all to be affirmed by the Saint himself… And as one of the blessed, Bob Marley tells us ‘We should really love each other / In peace and harmony’”. It was strange out of context to hear a Bob Marley quote that wasn’t followed by raucous coughing. To a quiet pattering of random instruments and the jingling of a few tambourines, Archbishop King stepped up to deliver praise unto God and the two big JCs, noting that Patron Saint John Will-I-Am Coltrane reminds us daily to be sure that “I Am” doing good “Will”, finally explaining the oddly contemporary spacing of Coltrane’s middle name. King adjusted his saxophone and began to play the closing prayer. Everyone stood and began shaking hands, “God be with you”. I bought a postcard and left.It didn’t matter that I was a post-Stalinist atheist vis-à-vis religion, and Jewish vis-à-vis wintertime holidays, that much was clear when I walked through the door. Nobody was looking to proselytize me; there was no grand message about abortion or evolution, and for once nobody was talking about gay right or politics. There was God, Jesus Christ, and John Coltrane. I stood across the street waiting for the bus as King’s sax echoed out the door, and God saw that it was good.Jules Suzdaltsev is on Twitter. Follow him - @jules_su

The reading was about coming closer to God through self-improvement and avoiding manifest corruption though words and action. She spoke about Coltrane’s handwritten outline of "A Love Supreme," where he had written a “musical recitation of prayer by horn,” and an “attempt to reach transcendent level with orchestra rising harmonies to a level of blissful stability at the end”. Sister King said that “although our faith has been tested by some who might not take us seriously, it should please us all to be affirmed by the Saint himself… And as one of the blessed, Bob Marley tells us ‘We should really love each other / In peace and harmony’”. It was strange out of context to hear a Bob Marley quote that wasn’t followed by raucous coughing. To a quiet pattering of random instruments and the jingling of a few tambourines, Archbishop King stepped up to deliver praise unto God and the two big JCs, noting that Patron Saint John Will-I-Am Coltrane reminds us daily to be sure that “I Am” doing good “Will”, finally explaining the oddly contemporary spacing of Coltrane’s middle name. King adjusted his saxophone and began to play the closing prayer. Everyone stood and began shaking hands, “God be with you”. I bought a postcard and left.It didn’t matter that I was a post-Stalinist atheist vis-à-vis religion, and Jewish vis-à-vis wintertime holidays, that much was clear when I walked through the door. Nobody was looking to proselytize me; there was no grand message about abortion or evolution, and for once nobody was talking about gay right or politics. There was God, Jesus Christ, and John Coltrane. I stood across the street waiting for the bus as King’s sax echoed out the door, and God saw that it was good.Jules Suzdaltsev is on Twitter. Follow him - @jules_su

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement