Talking to Van Dyke Parks is like being shot up with anti-depressants as you ride a horse through the Swiss Alps in late spring. For those who don't know much him other than his Beach Boys association (he holed up with Brian Wilson for over a year to create a set of songs that, though unfinished, managed to completely recalibrate popular music), try thinking of him as a Southern Gothic Scott Walker. But where Walker responded to all the hippy detritus of the time by looking outwards to Europe, Van Dyke responded by looking inwards, and way back, all the way back to America in the late 19th Century. He said he thought of himself in the 60's as counter counterculture. Like Walker, while everyone was getting weird he decided to go straight, though a twisted, Faulknerian, amphetamine head's version of straight.Van Dyke Parks caused a good deal of mind-unraveling to my late teenage self. His look on the cover of Song Cycle, understated, spaced out, and aloof, paired with the spiraling drug nostalgia of the music within, was the perfect delivery from an average life on earth.Around that time I became exposed to other subtlety out pop musicians—Mayo Thompson, Scott Walker, people like that. They were changing my world, revealing some kind of "third way" songwriting. Van Dyke fit in beautifully. It was because of him I cut my hair and for a few months in 1999 dressed like a warped 50's academic, a walking inside joke of olive corduroy, tweed jackets, and severely dilated pupils. He was my one-hitter and Adderall companion, orchestrating many a long stare out the window that fall.His first album, Song Cycle, defined a sound with its orchestrated pop; you've heard it imitated many times since, whether you're aware of it or not. In the mid-to-late 60's everyone wanted a piece of him. He was Brian Wilson's muse for Smile, the abovementioned aborted follow-up to Pet Sounds, the Byrds asked him to join their group at the height of their fame, so did Frank Zappa, so did, strangely, proto-boy band Crosby, Stills and Nash (happy he said no to that one, that would have been weird).I only partially knew the rest of his story, which includes years of deep immersion in the West Indies, hanging out with Albert Einstein, and writing the theme song to Jungle Book ("Bear Necessities," best song ever) as just a couple examples.I thought it would be better to have Van Dyke navigate his musical landscape himself, so I asked him to compile a list of his life's ten most pivotal musical moments, which he was gracious enough to do. I was then lucky enough to get to talk to him about it all, and about his most recent studio album, Songs Cycled, released this past July on Bella Union.Noisey: What I wanted to do was first talk a little about your list of the most pivotal musical moments in your life, and then speak to you about your new album. I really loved the first two moments you mentioned—your first time hearing Spike Jones and later Les Paul and Mary Ford. It was pretty amazing to hear those songs – they sound like the building blocks for your first solo record (Song Cycle).

Van Dyke Parks: Isn't it beautiful? Yeah come on, its so goddamn beautiful! You see that video? She was so calm, cool, collected, and he was off the planet! She was like watching a spaceship descend. Kansas, man. Also, when I was a kid she certainly wasn't my mom. Her voice was seductive.Did you form a conscious collection of those early influences for what became Song Cycle?

I wouldn't think so—certainly not consciously. You are very much a product of your environment. I liked every bit of it. I liked big band era, rockabilly, Sons of the Pioneers…I have had a chance to consider a lot of idioms.Recently, three years ago, a man called me up, an American Indian, Jimmy Carl Black. He was living in Hamburg, I believe, and he had been in the Mothers of Invention. He said, "Man we're starting a tour and calling it the Grand Mothers of Invention with some of the guys," wanted to know if I'd join. I said I'd rather not. It's too bad, as he died recently…so there are few standing…that aren't in prison.You wrote that in1952, at age nine, you headed off to boarding school to study music, and in the following six years your life kind of exploded musically: you played a role in "La Boehme" at the Metropolitan Opera, sang with the boys' choir at Carnegie Hall, and sang the title role of "Amahl" at the New York City Opera. Can you tell me about that early transition of yours and that period of studying music?

I'm studying music now. It's not like I've figured out how to do something. I don't know how to do anything. I know why I do something…and I know I have a few songs to distract me before I get to that really big symphony that will blow everybody right away. But I must wait, dishes to do, bills to pay…and stuff.Rearranging a song is an unknown quality of my occupational yield, and something I do a lot of. You can hear it on this record with something like "Amazing Graces." I like to reexamine a piece to see where it can go harmonically and in attitude, to keep that sense of discovery, so the arrangements feel like they have some extemporaneous reason for being, or lack of reason even.You said that in the 60's you were interested not only in the counterculture, but in being counter counterculture. And part of what I always loved about your records was that they did always exist outside the common practice of the time, and for me, almost had a punk rock attitude to them. Who in particular in the counter counterculture did you feel an affinity with?

Well…I never meant to piss anyone off with anything I've done, but sure, let hell break loose beyond that. But I want the stuff to be listenable and beautiful…I think that's job one, to make the world a more beautiful place. I'm in earnest about it when I write a song.Right, I didn't meant to say I think you're antagonistic or musically similar to punk rock, I just meant your music has a similarly independent agenda.

That's expensive! It takes a lot of courage. You're not always driven by profit in such a case. It's interesting for me that sellout in the US and in German, "ausevrkauf,"can be terrific and it can also be absolutely tarnished. I try to be most careful about my choices in life. I don't want to be timid. I cannot apologize for having any limitation, I must pursue…The Liverpool Taxi Drivers Society have an actual shield and on it these words are written: "Boldly going forward because we can't find reverse."If you just accept that in music…you have to be able to take risks. You might throw the equation of risk-benefit away because you have something far more important to do. By important I don't mean capital "I" important, because a song is also supremely unimportant and isn't something that has to grab people by the throat. For me it's so amorphous.There's this big word, it's almost bigger than quirky. The word is "compelling." Roger Ebert, people like this. There is something compelling about writing a song and it takes a lot of work. It does in my case. The biggest problem is just getting something out in completion, getting out of the shower and getting dry enough so that you're not gonna fall on your ass on your way to the desk. For me that's the work. And odds are you're not gonna catch it…. It's really born of inquiry; I enjoy that aspect of my life.The process requires patience…

In my case—might not be with anyone else—it's death defying. It's serious business. It's dangerous to have to deliver a song on a deadline. One time I was working on a children's television show, it was called Harold and the Purple Crayon. I was working for this guy—each show had to have one song, but the song was to appear with a different attitude and different words. It's a lot of work within a deadline of a week. I go into the bullshit session, called a production meeting, and the guy says Harold's goldfish dies, and when it dies, that's when Harold breaks into song. And the last thing he shoots at me is "don't forget you may be addressing an unattended 3-year-old child." I knew I couldn't go to Jesus, because Jesus stares too much for a 3-year-old, and Buddha, he's laughing and looks like he's crazy, plus he's got the obesity issue. So I just got out a seeetar and, as they say, feather or dot, I got dot. (LAUGHS) Life is an endless cycle…it was like being in an Escher picture. I went Bollywood when the goldfish dies.So just to know the song form drives you there is a big deal; it's a big interest to me…inevitably I come to the conclusion that the song form is a great central theme in a life well lived.Hearing you say that makes me think it might be good to start asking you some questions about the new record. There seem to be these reoccurring themes in your music over the years, and there are some that I clearly hear in both Song Cycle and in your newest record, Songs Cycled. You refer a lot to specific people and places, and the most defined place that appears to have an influence on your work is the South. I thought it was interesting that you included "The All Golden" on the new record (a song from Van Dyke's first record Song Cycle), it seemed like a significant choice. How would you define the influence the South has had on your music?

Well…I don't feel like a Southerner, because I've been living the majority of my life in southern California. But of course I can remember how to remove a tick without, uh, losing the head and the skin; you don't need a lighted match to do it. Do you know what it is?No, tell me.

Counterclockwise. Yeah. Good stuff. And I know about lightning bugs and things. That's primary youth, and I think that's obviously a romantic idea. I think that people, every one of us, it's part of the human condition, wants to live in that place that is a handshake away…the place that we just left. And I don't mean to go for medical results…it's better now than ever. I'm talking about what we just left behind, what Mike Love, (LAUGHS) the genius from the Beach Boys, calls the "nostalgia belt." I think we all want that and all have a sense of place in it and certainly songs reveal that. I think that's fine, but I don't think that's anything to sustain a song. I think that's part of the connective tissue. The idea is to really have something in mind with a song.What I like is the short story in song. I like that, I like a song to go somewhere and create a definite sense of place and…and uh, if the South is a tool or gateway for that, well…that's just a deep true L.A. confession, that I'm not from this place where I am…that's a fact.I'm just a stranger in paradise. (LAUGHS) Circling the drain with a bunch of attorneys. (LAUGHS)Beautiful.

And I like "the All Golden" because…I was just with the doctor the other day and he told me to get prehistoric with my diet and I'll be a much happier man. Go before agriculture…he's reminding me cause there's nothing like a good chophouse to drive me nuts…awful is good.Anyway, it's a fact that "The All Golden" is all about an agrarian world, an idealized place. And yet that's what the title suggests. It comes from a great uncle of mine, Will Carlton, he wrote a poem about the All Golden. It wasn't a very good poem, but he said in the foreword of his book that he wrote these pieces behind the heat of the team, the heat of the team was the horses of course…Behind the…say that again?

The heat, the heat of the team…the heat generated from the body of the horses pulling his plow. Back in the era of International Harvester…a plow built to till the land. And so I liked that world, I like the American century…the 19th Century was known as the American Century. That to me is something that is pathetic to remember as the Chinese contemplate ways to turn this hemisphere into their playground.So I think about the American Century…but the lyric as you know is all about my protest of war. And I think it's good to do that for the children of today, to remind them that war is anachronistic, it doesn't work. We went to Vietnam and saw what bombs do. What was that stuff? Napalm…they drop it on burning babies and serve it up to our news service at 6 pm. I've seen war and war is hell. And now we're just leaving there, Afghanistan, without an apology.So my songs have become politicized, and I'm not grumpy, I'm very happy. I have so many opportunities that are beckoning with no certainty, but I can gladly tell you… I'd rather be me. (LAUGHS)I'm just so happy to be alive I swear to you. They're dropping like flies; I'm in that zone.I want to pull back for a moment…you were talking about "The All Golden" and a reflection on an agrarian past, and I wanted to ask if Steve Young, as a person, represented all that to you somehow…(the original version of "The All Golden" was both written about and included vocals from musician Steve Young).

Yeah…well Steve Young, of course, is a unique individual. He's got Scottish blood in him; he has Indian blood in him, Cherokee. He's the only man I know who had to pick cotton as a boy. I just like to single out the people I know who…Well, you know we're all corruptible, but to meet someone who hasn't been corrupted in so many ways, though you'll never find perfection in a person, as Br'er Rabbit once said, "nobody's human," but the thing is I admire him for his principles and so forth. He was one of the people I met at that time, in the 60's…it was obvious he wasn't out for a fast buck, and I knew so many who were, whose mouths were in the troth, and his mouth was never in the troth.And I enjoy the fact that I wrote a song about somebody. He had an apartment in Silver Lake atop an oriental food store. And of course, little did I know that "oriental" would become a word to avoid, but at that time it was part of his exotic nature.He was an outsider really, right? I mean the country people rejected him…

Oh yes, absolutely. I liked that. Steve Young was the…whaddya call it? Waylon Jennings adopted this persona…"Outlaw," "Country Outlaw." It was a genre. "Country Outlaw," Waylon Jennings wanted to be Steve Young. That's what he said.There are other people who are like that…One night in a coffee shop in 1962 John Hammond came in right off a motorcycle having crossed the United States, blues singer John Hammond, a man just slightly older than me with the dust of the road on his face. And he wanted to get in on a set with his guitar, which he had strapped to his bike, a Harley. It's just amazing to me. He was the road warrior I wanted to be.I have nothing in common with Steve Young except that we were both ashamed of our origin at the time. He had a picture of George C. Wallace, the governor of Alabama, with a Hitlerian (sic) mustache emblemmed (sic) on his lip. Steve questioned authority, and record executive authority. He talked us out of a record contract I think at Columbia, either Columbia or Capital, I can't remember. So, to me you know…"Make new friends keep the old, one is silver the other is gold." That's what I do with Steve.Are you in touch still?

Yeah, he'll call me on occasion. We'll shoot the breeze; he's in Nashville.I just have one more question, directly related, it's about people. In the new record you have extensive liner notes that include character portraits of artists. People seem to be a consistent part of your musical life, people you admire, and collaborate with, and I wanted to know if you could tell me a little more about that.

Well, you know, if you look at the Song of Solomon, which is not in the Bible but it's connected to it, it's a great…love poem. It just captures the nature of love…another book, of kind of an epiphany, the Ecclesiastes, talks about…"now let us praise famous men, revelations, and praise those of no name, whose graves will never be known." And the idea is, I've always been interested, not so much in the power of celebrity, I know that's very exciting and erotic in a way, but I've always been interested in the info you get from what is of seemingly less importance, and that's is in social affairs too. You don't always have to seek out a crowd that is a steppingstone to the next job opportunity. So I like to take the road less traveled, socially, and I also do it by trying to surround myself with people I actually look up to. I have had a pattern of that in my work, that there are people around who are more able.Now, I'm very happy you mentioned those essays in the record, let's call it an album, because what it represents is their struggle…and the backstory is really the front story. This record is really a gathering of artists of different sorts, both visual and audio, and I am blown away by the power of anecdote in them. To have an artist on my record who actually saw Dylan Thomas fall off a barstool! In 1948! To see Simone de Beauvoir in Paris…and look at the others, look at Billy Edd, from his coal mine to Yale! He did that great acrylic for "Sassafrass," the song he wrote. I had to salute him, in his time. I think he's 84…(LONG PAUSE)So…hey man, it's a great adventure.VAN DYKE PARKS' MOST PIVOTAL MUSICAL MOMENTS (by Van Dyke Parks)

Summer of 1948 – Spike Jones & His City Slickers – "Cocktails for Two"I was all ears at age five. I started lessons on an old clarinet. Its ancient Albert system of fingering was tough going around corners, like driving a Hudson Hornet without power steering. Our family was all music. I (was the) youngest of four boys of a father who'd been a dance band leader. "Dick Parks and His White Swan Serenaders" had held forth at the White Swan Hotel in Punxsutawney, PA. We listened to big band on 78s. Our go-to clarinetist was Artie Shaw. (Benny Goodman was Plan B on our Magnavox). My mother was a spectacular pianist as well. She and Dad played duets on the two nested grand pianos in our living room, or swept the floor in a jitterbug, fox-trot, or waltz. Music us boys were taught came from notation: songs on sheet music, instrumental pieces on well-thumbed, dog-eared old volumes passed down to us by great aunts and uncles. As a rule, if it wasn't on the page, it wasn't on the stage. We got good enough to hit the Yuletide hood with clarinet, cornet, French horn, and a double-barrel euphonium. Our live music was not only made in our living room but at church too. Those hymns were mainly Wesleyan. John and Charles' tunes formed the backbone of my musical perspective.

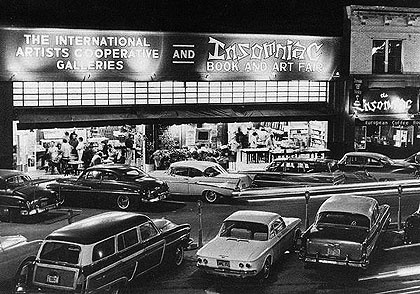

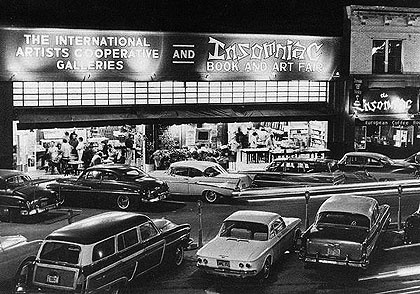

So, in 1948 I became aware of recorded music. One record that would change the way I looked at the world of music was "Cocktails for Two" by Spike Jones & His City Slickers. That tune was written to celebrate the end of Prohibition, and was featured on his album "Dinner Music for People Who Aren't Very Hungry." Spike's arrangements were filled with tuneful percussion. It was ear candy to me, so used to "legit" music. Whoopie cushions and breaking glass were intermingled with xylophones marimbas—smells, bells, and yells from an entirely different kind of musical liturgy. Spike Jones' menu changed my musical appetite for the rest of my life, spinning me off into a world of recorded sound. Pivotal!1951: Les Paul & Mary Ford - "How High the Moon" Playing at "The Insomniac" coffee house in Hermosa Beach with my brother. The opening act was Andrew de la Bastide and his Trinidad Steel Band. An immersion in Calypso that brought world beat to my Beat Era. Riveting and pivotal.In 1963, I got my first Musicians' Union check for arranging "The Bear Necessities" for Disney's "Jungle Book." That was thanks to songwriter Terry Gilkyson who'd seen me and my brother play in local coffee house. That job began my obsession for arranging. Pivotal!In 1964, producer Tom Wilson (who'd signed Bob Dylan to a record contract the year before) decided I was an "artist" and signed me to MGM Records. I wasn't too sure that was smart, but it sure was pivotal.In 1964, I quit "The Mothers of Invention" when I decided I didn't want life in live music. I'd conned Del Casher (who invented the Wah-Wah pedal) to join the group. I left him there, with Zappa, at the Shrine auditorium. I was magnetized by the potential of the studio. I became a short list keyboard studio player. That was a real fork in the road.

Playing at "The Insomniac" coffee house in Hermosa Beach with my brother. The opening act was Andrew de la Bastide and his Trinidad Steel Band. An immersion in Calypso that brought world beat to my Beat Era. Riveting and pivotal.In 1963, I got my first Musicians' Union check for arranging "The Bear Necessities" for Disney's "Jungle Book." That was thanks to songwriter Terry Gilkyson who'd seen me and my brother play in local coffee house. That job began my obsession for arranging. Pivotal!In 1964, producer Tom Wilson (who'd signed Bob Dylan to a record contract the year before) decided I was an "artist" and signed me to MGM Records. I wasn't too sure that was smart, but it sure was pivotal.In 1964, I quit "The Mothers of Invention" when I decided I didn't want life in live music. I'd conned Del Casher (who invented the Wah-Wah pedal) to join the group. I left him there, with Zappa, at the Shrine auditorium. I was magnetized by the potential of the studio. I became a short list keyboard studio player. That was a real fork in the road.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Van Dyke Parks: Isn't it beautiful? Yeah come on, its so goddamn beautiful! You see that video? She was so calm, cool, collected, and he was off the planet! She was like watching a spaceship descend. Kansas, man. Also, when I was a kid she certainly wasn't my mom. Her voice was seductive.Did you form a conscious collection of those early influences for what became Song Cycle?

I wouldn't think so—certainly not consciously. You are very much a product of your environment. I liked every bit of it. I liked big band era, rockabilly, Sons of the Pioneers…I have had a chance to consider a lot of idioms.Recently, three years ago, a man called me up, an American Indian, Jimmy Carl Black. He was living in Hamburg, I believe, and he had been in the Mothers of Invention. He said, "Man we're starting a tour and calling it the Grand Mothers of Invention with some of the guys," wanted to know if I'd join. I said I'd rather not. It's too bad, as he died recently…so there are few standing…that aren't in prison.

Advertisement

I'm studying music now. It's not like I've figured out how to do something. I don't know how to do anything. I know why I do something…and I know I have a few songs to distract me before I get to that really big symphony that will blow everybody right away. But I must wait, dishes to do, bills to pay…and stuff.Rearranging a song is an unknown quality of my occupational yield, and something I do a lot of. You can hear it on this record with something like "Amazing Graces." I like to reexamine a piece to see where it can go harmonically and in attitude, to keep that sense of discovery, so the arrangements feel like they have some extemporaneous reason for being, or lack of reason even.You said that in the 60's you were interested not only in the counterculture, but in being counter counterculture. And part of what I always loved about your records was that they did always exist outside the common practice of the time, and for me, almost had a punk rock attitude to them. Who in particular in the counter counterculture did you feel an affinity with?

Well…I never meant to piss anyone off with anything I've done, but sure, let hell break loose beyond that. But I want the stuff to be listenable and beautiful…I think that's job one, to make the world a more beautiful place. I'm in earnest about it when I write a song.

Advertisement

That's expensive! It takes a lot of courage. You're not always driven by profit in such a case. It's interesting for me that sellout in the US and in German, "ausevrkauf,"can be terrific and it can also be absolutely tarnished. I try to be most careful about my choices in life. I don't want to be timid. I cannot apologize for having any limitation, I must pursue…The Liverpool Taxi Drivers Society have an actual shield and on it these words are written: "Boldly going forward because we can't find reverse."If you just accept that in music…you have to be able to take risks. You might throw the equation of risk-benefit away because you have something far more important to do. By important I don't mean capital "I" important, because a song is also supremely unimportant and isn't something that has to grab people by the throat. For me it's so amorphous.There's this big word, it's almost bigger than quirky. The word is "compelling." Roger Ebert, people like this. There is something compelling about writing a song and it takes a lot of work. It does in my case. The biggest problem is just getting something out in completion, getting out of the shower and getting dry enough so that you're not gonna fall on your ass on your way to the desk. For me that's the work. And odds are you're not gonna catch it…. It's really born of inquiry; I enjoy that aspect of my life.

Advertisement

In my case—might not be with anyone else—it's death defying. It's serious business. It's dangerous to have to deliver a song on a deadline. One time I was working on a children's television show, it was called Harold and the Purple Crayon. I was working for this guy—each show had to have one song, but the song was to appear with a different attitude and different words. It's a lot of work within a deadline of a week. I go into the bullshit session, called a production meeting, and the guy says Harold's goldfish dies, and when it dies, that's when Harold breaks into song. And the last thing he shoots at me is "don't forget you may be addressing an unattended 3-year-old child." I knew I couldn't go to Jesus, because Jesus stares too much for a 3-year-old, and Buddha, he's laughing and looks like he's crazy, plus he's got the obesity issue. So I just got out a seeetar and, as they say, feather or dot, I got dot. (LAUGHS) Life is an endless cycle…it was like being in an Escher picture. I went Bollywood when the goldfish dies.So just to know the song form drives you there is a big deal; it's a big interest to me…inevitably I come to the conclusion that the song form is a great central theme in a life well lived.Hearing you say that makes me think it might be good to start asking you some questions about the new record. There seem to be these reoccurring themes in your music over the years, and there are some that I clearly hear in both Song Cycle and in your newest record, Songs Cycled. You refer a lot to specific people and places, and the most defined place that appears to have an influence on your work is the South. I thought it was interesting that you included "The All Golden" on the new record (a song from Van Dyke's first record Song Cycle), it seemed like a significant choice. How would you define the influence the South has had on your music?

Well…I don't feel like a Southerner, because I've been living the majority of my life in southern California. But of course I can remember how to remove a tick without, uh, losing the head and the skin; you don't need a lighted match to do it. Do you know what it is?

Advertisement

Counterclockwise. Yeah. Good stuff. And I know about lightning bugs and things. That's primary youth, and I think that's obviously a romantic idea. I think that people, every one of us, it's part of the human condition, wants to live in that place that is a handshake away…the place that we just left. And I don't mean to go for medical results…it's better now than ever. I'm talking about what we just left behind, what Mike Love, (LAUGHS) the genius from the Beach Boys, calls the "nostalgia belt." I think we all want that and all have a sense of place in it and certainly songs reveal that. I think that's fine, but I don't think that's anything to sustain a song. I think that's part of the connective tissue. The idea is to really have something in mind with a song.What I like is the short story in song. I like that, I like a song to go somewhere and create a definite sense of place and…and uh, if the South is a tool or gateway for that, well…that's just a deep true L.A. confession, that I'm not from this place where I am…that's a fact.I'm just a stranger in paradise. (LAUGHS) Circling the drain with a bunch of attorneys. (LAUGHS)Beautiful.

And I like "the All Golden" because…I was just with the doctor the other day and he told me to get prehistoric with my diet and I'll be a much happier man. Go before agriculture…he's reminding me cause there's nothing like a good chophouse to drive me nuts…awful is good.

Advertisement

The heat, the heat of the team…the heat generated from the body of the horses pulling his plow. Back in the era of International Harvester…a plow built to till the land. And so I liked that world, I like the American century…the 19th Century was known as the American Century. That to me is something that is pathetic to remember as the Chinese contemplate ways to turn this hemisphere into their playground.So I think about the American Century…but the lyric as you know is all about my protest of war. And I think it's good to do that for the children of today, to remind them that war is anachronistic, it doesn't work. We went to Vietnam and saw what bombs do. What was that stuff? Napalm…they drop it on burning babies and serve it up to our news service at 6 pm. I've seen war and war is hell. And now we're just leaving there, Afghanistan, without an apology.So my songs have become politicized, and I'm not grumpy, I'm very happy. I have so many opportunities that are beckoning with no certainty, but I can gladly tell you… I'd rather be me. (LAUGHS)

Advertisement

Yeah…well Steve Young, of course, is a unique individual. He's got Scottish blood in him; he has Indian blood in him, Cherokee. He's the only man I know who had to pick cotton as a boy. I just like to single out the people I know who…Well, you know we're all corruptible, but to meet someone who hasn't been corrupted in so many ways, though you'll never find perfection in a person, as Br'er Rabbit once said, "nobody's human," but the thing is I admire him for his principles and so forth. He was one of the people I met at that time, in the 60's…it was obvious he wasn't out for a fast buck, and I knew so many who were, whose mouths were in the troth, and his mouth was never in the troth.And I enjoy the fact that I wrote a song about somebody. He had an apartment in Silver Lake atop an oriental food store. And of course, little did I know that "oriental" would become a word to avoid, but at that time it was part of his exotic nature.He was an outsider really, right? I mean the country people rejected him…

Oh yes, absolutely. I liked that. Steve Young was the…whaddya call it? Waylon Jennings adopted this persona…"Outlaw," "Country Outlaw." It was a genre. "Country Outlaw," Waylon Jennings wanted to be Steve Young. That's what he said.

Advertisement

Yeah, he'll call me on occasion. We'll shoot the breeze; he's in Nashville.I just have one more question, directly related, it's about people. In the new record you have extensive liner notes that include character portraits of artists. People seem to be a consistent part of your musical life, people you admire, and collaborate with, and I wanted to know if you could tell me a little more about that.

Well, you know, if you look at the Song of Solomon, which is not in the Bible but it's connected to it, it's a great…love poem. It just captures the nature of love…another book, of kind of an epiphany, the Ecclesiastes, talks about…"now let us praise famous men, revelations, and praise those of no name, whose graves will never be known." And the idea is, I've always been interested, not so much in the power of celebrity, I know that's very exciting and erotic in a way, but I've always been interested in the info you get from what is of seemingly less importance, and that's is in social affairs too. You don't always have to seek out a crowd that is a steppingstone to the next job opportunity. So I like to take the road less traveled, socially, and I also do it by trying to surround myself with people I actually look up to. I have had a pattern of that in my work, that there are people around who are more able.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Let's reconstruct the moment my head went through the windshield in this year when I first laid ears on this tune. YouTube it and you'll hear how multi-track recording turned me upside down, convincing me that I wanted to live in the world of recorded music. I bought that 45rpm vinyl single. When that needle hit the groove it introduced me to multi-track recording, one of the ten most pivotal musical moments in my life.

In 1952, I headed off to boarding school to study music at the Columbus Boy Choir School. It was actually outside of Princeton New Jersey on a great estate. My life would be filled with music of dead white guys…classical composers from the Middle Ages forward was all that I thought about, madrigals from England and France. An opera by the 12-year-old Mozart, which had premiered at a garden party for Dr. Mesmer (who discovered animal magnetism, making a racket outta hypnosis), sprechstimme by Schoenberg ("Pierrot Lunaire") presaged the kind of voice Bob Dylan would turn into global popularity. It was Nirvana for me, and I'd attend that school for the next six years graduating in 1957. During that time other pivotal musical events took place. I was a street urchin in "La Boheme" at the Metropolitan Opera. I sang with the boy choir at Carnegie Hall, and got to swing up to Toscanini's dressing room after the show (he was drinking beer and watching a boxing match on black & white TV). That year I sang "Stille Nacht" at the front porch of Albert Einstein, with him on a violin obligato (a few of us caroling boys then went in for another hour of tunes in his kitchen). Relatively pivotal…I sang the title role of "Amahl" at the New York City Opera (after an audition for its composer Gian Carlo Menotti). Is that pivotal or what?

Advertisement

In 1968, I signed as an artist at Warner Brothers. I'd make solo albums there (usually with large orchestras) and put all I learned to use as a producer for other people. Inclined to empowering others, I got my feet wet by co-producing the debut albums of Ry Cooder, then Randy Newman. I decided I liked being part of the team. Producing was a whole new way to make a positive difference in a war-ravaged world. I dug it. Producing became pivotal. It made it possible to be counterculture and simultaneously counter counterculture.By 1971 I'd seen enough struggling musicians become road-kill in drug-overdoses. I decided there must be another way for artists to make a decent buck with another income stream. It dawned on me that music videos were the key. So I set up an "Audio-Visual Services" department at Warner Brothers to make music-documentary shorts (WB was the first such record company department to do so). I saw to it that artists were paid royal royalties from these. The videos were built for first-run theaters and then some. WB decided to continue that idea, but to cut out the royalty rates. So I quit being an office boy and got back to free-lance producing and arranging, meeting musicians beyond the corporate fence. It opened up new worlds, to serve artists as magnetic as Harry Nilsson (a real genius).In 1977, Jack Nicholson offered me a soundtrack. Film composition had always fascinated me. Jack had offered me the chance twice before ("Easy Rider" and "Drive She Said"). I figured…third time's a charm! Sensing it was now or never, I took him up on it. Scoring for films and television (along with arranging) has been my means of self-support ever since. It got three offspring off through college, past the tuitional curveball, and made it possible for me to stay in the game, past the implosion of the music business, until I could return to the divine I find in vinyl, where it all began in my musically pivotal life.