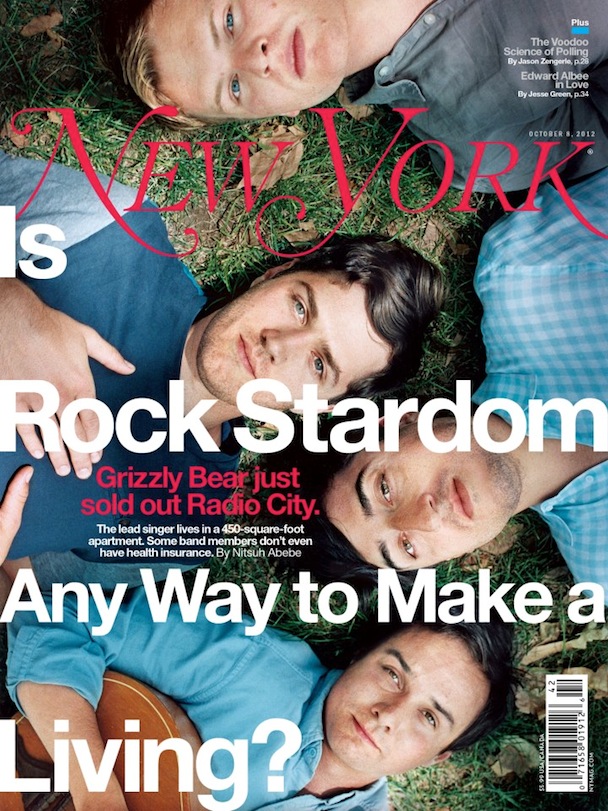

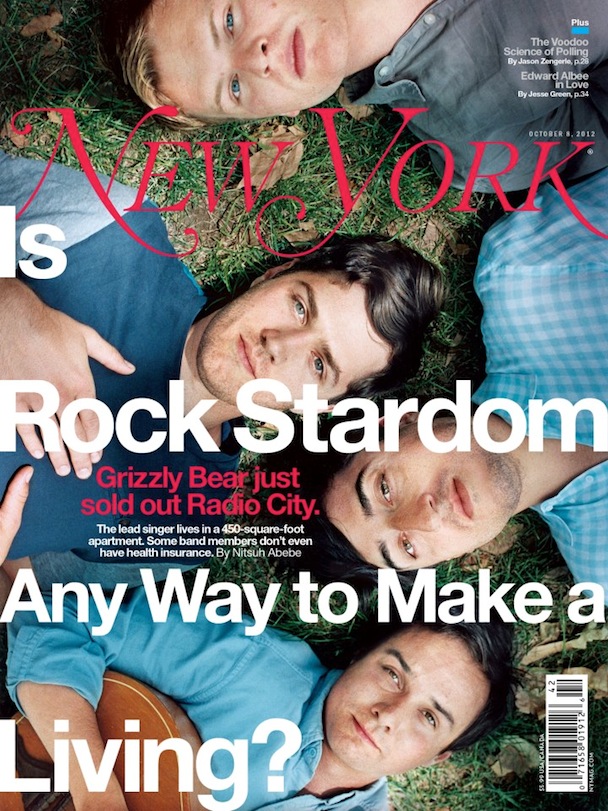

“The question of when we’ll be profitable actually feels irrelevant. Our focus is all on growth. That is priority one, two, three, four, and five. But of course, we expect to make a profit in the long run.”That's Spotify's CEO speaking. His company, by the way, recently reported losing over $100 million dollars during the past two years. This is, of course, an unsustainable amount of losses, which means that inevitably, the company will either A) go bankrupt, or B) rely almost entirely on paid subscriptions.The future of music listening is in streaming. There's no going back to CDs, of course, but MP3s are also on their way out (it's pretty hard to illegally download on an iPhone). Plus, it's really nice to be able to listen to any song you want at any time, which means: The future of music listening looks a lot like Spotify Premium, or, more broadly, an iTunes-like store that allows you unlimited listening to pretty much every song ever, in exchange for a small fee. How much will this cost? Well, how much can you afford? Because it will cost slightly less than that. I'm guessing it'll get to $20/month for ad-free listening, $10/month for a version with commercials, and maybe a free version that is filled with an almost unbearable number of ads.Mostly relieved from the responsibility that was paying for and coordinating the production of physical products (vinyl will hold steady), record labels will still be around to help coordinate tours, PR, and things of that nature. But their main function will be to serve as editors. In 2012, technology is such that anyone can make music; being signed to a label, then, will serve as a seal of approval, a signifier that the band you're listening to is believed in by the people who make believing in bands their business. In this sense, record labels will mirror art galleries, who, when dealing with lesser-known names, serve to legitimize the artists they represent. Moving on to the people who actually make music, let's look at Grizzly Bear, a band that represents essentially the upper-level of what an indie rock group can hope to be. Nitsuh "the God" Abebe recently profiled them for a New York cover story that gives the best look we've seen on the finances of indie success in 2k12. The band isn't rich, but, as Abebe later clarified on Slate's Culture Gabfest podcast, they're certainly doing fine. That said, they make literally dollars per month from Spotify, despite the fact that their songs are streamed, presumably, hundreds of thousands of times. What this implies is that, even if Spotify and similar services change how they pay, odds are that bands will never be able to make a living from them. So how does Grizzly Bear make their money? Licensing and touring.The economics of touring, and the new politics of selling out (hint: no one cares if your song is in a Prius commercial; it just makes people feel less guilty about downloading your music for free) have been extensively covered, so let's be brief. You can make a good deal of money from licensing your music. Not private jet amounts, but possibly late-model Honda amounts. More consistently though, you can also make good money touring, especially if you're filling venues. But, as I've said, this is well-tread territory. Let's get novel.Let's say you're some bedroom genius who doesn't want to tour. You don't want to license your music either. That's fine. Time was, you could still fall back on record sales. Now, let's ignore the fact that even in the CD's heyday, most bands had to tour, at least initially, in order to build a fan base (read: play for A&R reps and get signed to a label). Shouldn't the musician that just wants to create in isolation be able to earn a living (assuming the music is good enough)? Yes, but let's consider what this person who spends all their time perfecting their art sounds like: an artist. So why don't some musicians make money like artists?Artists sell their art, just as musicians do, the difference being that, traditionally, artists sell the entirety of something to one person for a large amount, whereas musicians sell the same product to many people for a small amount. But there's no reason that this need be the case. Yes, music is reproducible in a way that a painting is not, but photos (especially digital photos) and video art are equally reproducible.

Moving on to the people who actually make music, let's look at Grizzly Bear, a band that represents essentially the upper-level of what an indie rock group can hope to be. Nitsuh "the God" Abebe recently profiled them for a New York cover story that gives the best look we've seen on the finances of indie success in 2k12. The band isn't rich, but, as Abebe later clarified on Slate's Culture Gabfest podcast, they're certainly doing fine. That said, they make literally dollars per month from Spotify, despite the fact that their songs are streamed, presumably, hundreds of thousands of times. What this implies is that, even if Spotify and similar services change how they pay, odds are that bands will never be able to make a living from them. So how does Grizzly Bear make their money? Licensing and touring.The economics of touring, and the new politics of selling out (hint: no one cares if your song is in a Prius commercial; it just makes people feel less guilty about downloading your music for free) have been extensively covered, so let's be brief. You can make a good deal of money from licensing your music. Not private jet amounts, but possibly late-model Honda amounts. More consistently though, you can also make good money touring, especially if you're filling venues. But, as I've said, this is well-tread territory. Let's get novel.Let's say you're some bedroom genius who doesn't want to tour. You don't want to license your music either. That's fine. Time was, you could still fall back on record sales. Now, let's ignore the fact that even in the CD's heyday, most bands had to tour, at least initially, in order to build a fan base (read: play for A&R reps and get signed to a label). Shouldn't the musician that just wants to create in isolation be able to earn a living (assuming the music is good enough)? Yes, but let's consider what this person who spends all their time perfecting their art sounds like: an artist. So why don't some musicians make money like artists?Artists sell their art, just as musicians do, the difference being that, traditionally, artists sell the entirety of something to one person for a large amount, whereas musicians sell the same product to many people for a small amount. But there's no reason that this need be the case. Yes, music is reproducible in a way that a painting is not, but photos (especially digital photos) and video art are equally reproducible. Consider a recent high profile piece of video art: Christian Marclay's The Clock, a 24 hour film comprised of bits and pieces of films, some famous and others obscure, in which every moment of the day is represented on screen in real time (e.g. at 5pm in the theater, the screen may show a man punching out at work, and at 5am, you might see glimpse a scene with an alarm clock going off). Six copies of The Clock were sold for hundreds of thousands of dollars each. Now, presumably, Marclay still has the thing on his hard drive and could burn another copy if he wanted to, but he said he was going to sell a set number and that's what he did.We can all agree that music is art. Beyond that, I think that most people would agree that music is more popular than the kind of fine art that hangs in a gallery. So then: I bet there's a rich person who would pay a lot of money to be the owner of the next Arcade Fire album. Think of this as neo-Medici; it allows rich people to spend their money on something expensive (which is, honestly, the quotidian goal of most rich people) while doing the public a bit of good.So, what would said ownership of music look like? Well, I'm not a lawyer, but, presumably, bands and their benefactor(s) could work out an agreement that stipulates whatever they want. Maybe Feist gets $500,000 from someone for her album; in exchange, she writes a song named after the guy's son. Or the album cover says the rich person's name on it. Or they get to own the masters (maybe in a physical sense only, or maybe they get licensing rights too). Does everyone else get to hear the album? Well, presumably the musician wants to be heard and the buyer wants the world to know how good the thing they bought is. Just as lots of people like to loan their art to museums, the music could be hosted on Spotify (or iTunes, or wherever), "on loan from the Charney trust" or "thanks to the Roberta's Foundation." In fact, work could be sold on the condition that it be made for free to the listening public. Really, anything that musicians and their sponsors agree upon on would work. Yes, this whole system might have some kinks that need to be ironed out, but there's no reason that it wouldn't be better for artists than nothing, which is essentially what they're getting for their music right now.@hansonohaver

Consider a recent high profile piece of video art: Christian Marclay's The Clock, a 24 hour film comprised of bits and pieces of films, some famous and others obscure, in which every moment of the day is represented on screen in real time (e.g. at 5pm in the theater, the screen may show a man punching out at work, and at 5am, you might see glimpse a scene with an alarm clock going off). Six copies of The Clock were sold for hundreds of thousands of dollars each. Now, presumably, Marclay still has the thing on his hard drive and could burn another copy if he wanted to, but he said he was going to sell a set number and that's what he did.We can all agree that music is art. Beyond that, I think that most people would agree that music is more popular than the kind of fine art that hangs in a gallery. So then: I bet there's a rich person who would pay a lot of money to be the owner of the next Arcade Fire album. Think of this as neo-Medici; it allows rich people to spend their money on something expensive (which is, honestly, the quotidian goal of most rich people) while doing the public a bit of good.So, what would said ownership of music look like? Well, I'm not a lawyer, but, presumably, bands and their benefactor(s) could work out an agreement that stipulates whatever they want. Maybe Feist gets $500,000 from someone for her album; in exchange, she writes a song named after the guy's son. Or the album cover says the rich person's name on it. Or they get to own the masters (maybe in a physical sense only, or maybe they get licensing rights too). Does everyone else get to hear the album? Well, presumably the musician wants to be heard and the buyer wants the world to know how good the thing they bought is. Just as lots of people like to loan their art to museums, the music could be hosted on Spotify (or iTunes, or wherever), "on loan from the Charney trust" or "thanks to the Roberta's Foundation." In fact, work could be sold on the condition that it be made for free to the listening public. Really, anything that musicians and their sponsors agree upon on would work. Yes, this whole system might have some kinks that need to be ironed out, but there's no reason that it wouldn't be better for artists than nothing, which is essentially what they're getting for their music right now.@hansonohaver

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement