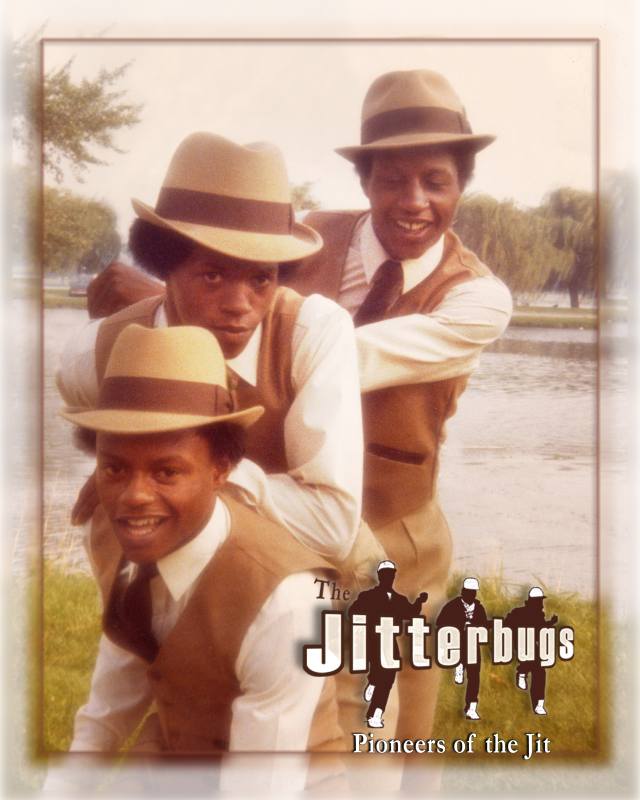

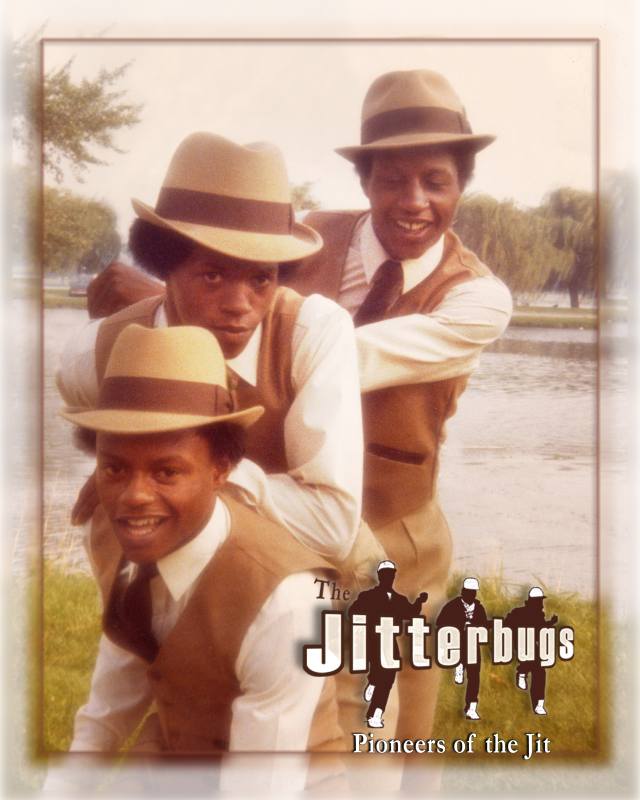

Photo by Pete DeevakulLast Friday, crowds packed into the Detroit Institute of Art's Detroit Film Theatre for a red carpet event. But while the massive collection at the acclaimed public museum is a draw—as well as a centerpiece in the city's ongoing bankruptcy drama—it was a different kind of local art that was about to be on display, one that hasn't always gotten the same attention as its home city's other creative and musical accomplishments. Alongside the well-to-do museum benefactors of Detroit’s elite, older generation who typically frequent the Art Institute’s events was a younger crowd there specifically to support local graffiti artist turned dancer turned documentarian Haleem Rasul, a.k.a. Stringz, who was premiering a documentary he made and produced called The Jitterbugs: Pioneers of the Jit. Prior to the evening, the older benefactors may not have had much of an idea as to what the street dance sub-culture they were there to learn the history of is all about—but, then again, not many other people do either.If you've never heard of jit dancing or a jitterbug or jitter, the person who practices it, you're not alone. Jit dancing and the electronic music genre ghettotech that often accompany it are to Detroit what popping and funk were to the West Coast, what breaking was to East Coast hip-hop, and what footworking was to Chicago juke in the 1970s, 80s and mid-2000s, respectively. Dating back to the 1970s, jit, at its core, relies on a combination of fancy footwork, accompanied by dramatic drops to the floor, spinning and popping in one fluid motion, all moving to music set at 150 BPM. Its contemporary musical counterpart, ghettotech, has influenced the likes of MC Hammer, Lil John and Diplo. But while the street styles of Los Angeles, New York and to a lesser degree Chicago have realized a widespread following, jit has not yet enjoyed commercial appeal or broad awareness.Stringz's documentary aims to change that. The film is dominated with recollections from the three brothers who founded jit, Johnnie, James, and Tracy McGhee. It takes viewers into the brothers' home in the 70s, the place where they got their start performing at backyard house parties accompanied by local Motown music. The self-described hooligans recall using Detroit's decaying urban landscape as their dance floors, literally jumping from the rooftops—abandoned house to abandoned house. To excite the crowd, they would hop onto a roof and perform, eventually leaping onto a neighboring roof as part of their routine. The film goes on to illustrate their rise to small-scale fame when they caught the attention of Motown legend Kim Weston, as well as their eventual fall when oldest brother James fell into the throes of drug addiction. While the film focused mainly on the McGhees' story, a performance following the movie by several younger jit dance crews and the sounds of Detroit's The Untouchables showcased where the dance style is today. The story of this Detroit style, which has experienced several waves of emerging popularity and dormancy, is as complicated as Detroit itself, a city that revolutionized electronic dance music in much the same way it did the American automotive industry but never fully got the recognition it deserves. Much like the techno music born in the Motor City, which found mainstream success overseas but not initially in its own backyard, Stringz and his own crew, HardCore Detroit, have traveled the world, including stints throughout Europe and Asia, showcasing jit at workshops for youth dance groups.The current form of Detroit jit came of age in the 90s and 2000s at the same time that the city's techno sound was making waves all over Europe. Even though techno and, later, ghettotech were being played all over local radio stations, the latter never fully realized commercial success in Detroit—mainstream radio just couldn't seem to fit it into a marketable category. How were Top 40 stations supposed to make money off a genre deeply rooted in urban black culture? Despite the lack of commercial appeal, ghettotech and jit thrived in the underground and often intermingled with Chicago's juke scene, and around the same time that ghettotech was making inroads during boiler room sets throughout the Midwest, jit had its latest reemergence as jitters started showing off their moves to a captive Chicago audience.

While the film focused mainly on the McGhees' story, a performance following the movie by several younger jit dance crews and the sounds of Detroit's The Untouchables showcased where the dance style is today. The story of this Detroit style, which has experienced several waves of emerging popularity and dormancy, is as complicated as Detroit itself, a city that revolutionized electronic dance music in much the same way it did the American automotive industry but never fully got the recognition it deserves. Much like the techno music born in the Motor City, which found mainstream success overseas but not initially in its own backyard, Stringz and his own crew, HardCore Detroit, have traveled the world, including stints throughout Europe and Asia, showcasing jit at workshops for youth dance groups.The current form of Detroit jit came of age in the 90s and 2000s at the same time that the city's techno sound was making waves all over Europe. Even though techno and, later, ghettotech were being played all over local radio stations, the latter never fully realized commercial success in Detroit—mainstream radio just couldn't seem to fit it into a marketable category. How were Top 40 stations supposed to make money off a genre deeply rooted in urban black culture? Despite the lack of commercial appeal, ghettotech and jit thrived in the underground and often intermingled with Chicago's juke scene, and around the same time that ghettotech was making inroads during boiler room sets throughout the Midwest, jit had its latest reemergence as jitters started showing off their moves to a captive Chicago audience. Photo by Andy TanguayWhile jitters kind of fell into the rhythm of the music, Chicago dancers took it up a notch. Jitters move to ghettotech beats at 150 BPM, but Chicago footworkers speed the tempo up to 160-170 BPM to juke in a more aggressive step. Jitters stay in sync with soulful tracks, while footworkers engage in battles where the intended outcome is to move their feet as quickly as possible. If the two were a sport, Detroit would be about choreography, style, and rhythm, and Chicago would be about speed and one-upmanship.Given its history and influence, then, why hasn't Detroit's street dance culture gotten its respect? According to Antoine “Striz” Terhune, of East Side Detroit’s World Threat jit crew, Detroit has been in the shadows for three decades, save for the occasional story about how it’s the country's murder capital. A city like Chicago, on the other hand, “the third largest city in America, of course, is going to have the spotlight.” Stringz adds that Detroit jit and the music that goes along with it "has been around a lot longer than Chicago. We already had a movement, but what Chicago had was the cameras. They kind of got the spotlight and whoever gets it first gets the credit.”Martez Claybren, 21, a club kid who organizes underground techno parties—including the Chicago-Detroit juke and ghettotech party at North End Studios last month that generated headlines as Chicago footwork pioneer DJ Rashad was supposed to play the night of his death— says there’s a lukewarm taste for jit among peers his age, even though we noticed jitters were in full force at Martez's most recent event. “In current day Detroit, there is not a proper platform for the up-and-coming new composers of the ghettotech or jit scene,” he told us “Because of this, the relationship between the youth and their exposure to art forms has declined, leading to a wavering in the connection between the style itself and the community.” Youth his age are not even old enough to get into the parties that might play this stuff. What the jit scene is left with is an aging following that does not have the next generation taking the torch, he says

Photo by Andy TanguayWhile jitters kind of fell into the rhythm of the music, Chicago dancers took it up a notch. Jitters move to ghettotech beats at 150 BPM, but Chicago footworkers speed the tempo up to 160-170 BPM to juke in a more aggressive step. Jitters stay in sync with soulful tracks, while footworkers engage in battles where the intended outcome is to move their feet as quickly as possible. If the two were a sport, Detroit would be about choreography, style, and rhythm, and Chicago would be about speed and one-upmanship.Given its history and influence, then, why hasn't Detroit's street dance culture gotten its respect? According to Antoine “Striz” Terhune, of East Side Detroit’s World Threat jit crew, Detroit has been in the shadows for three decades, save for the occasional story about how it’s the country's murder capital. A city like Chicago, on the other hand, “the third largest city in America, of course, is going to have the spotlight.” Stringz adds that Detroit jit and the music that goes along with it "has been around a lot longer than Chicago. We already had a movement, but what Chicago had was the cameras. They kind of got the spotlight and whoever gets it first gets the credit.”Martez Claybren, 21, a club kid who organizes underground techno parties—including the Chicago-Detroit juke and ghettotech party at North End Studios last month that generated headlines as Chicago footwork pioneer DJ Rashad was supposed to play the night of his death— says there’s a lukewarm taste for jit among peers his age, even though we noticed jitters were in full force at Martez's most recent event. “In current day Detroit, there is not a proper platform for the up-and-coming new composers of the ghettotech or jit scene,” he told us “Because of this, the relationship between the youth and their exposure to art forms has declined, leading to a wavering in the connection between the style itself and the community.” Youth his age are not even old enough to get into the parties that might play this stuff. What the jit scene is left with is an aging following that does not have the next generation taking the torch, he says Stringz / Photo by Lena LeeWith initiatives like the documentary, his outreach work, and his own dance crew, Stringz is fighting against shunting aside of the art form. We followed him one recent Monday night, at his studio, which also serves as an inner city youth summer camp activity hall, with a worn concrete floor with painted on cobble stones, tall ballerina mirrors and a mix of rudimentary murals and graffiti art painted on the walls. Little by little, Stringz greeted crew members and they started breaking. The crew is made up of teenage white boys from the suburbs, Iraqi immigrants seeking asylum in Metro Detroit, and a handful of b-girls, among others. They threw on knitted beanie hats and got to work on head spins, windmill swipes and freezes, while hard techno and funk blasted from an amplified iPhone's playlist.After the practice session, we headed over to The Ritz, just as DJ Row was setting up his equipment. He's been on the scene since the early 90s, back when jitters were doing their moves at Northland Roller Rink. On this night, he was gearing up for Open Circle Mondays, where veteran jit dancers and newcomers alike can showcase and battle. At first glance the Ritz looks and feels like your run-of-the-mill Midwestern dive-club shithole, the kind of place where you order Bud Lights by the bucketful and meet up with coworkers from the nearby GM and Chrysler plants for happy hour or to watch grungy garage bands. Surrounded by acres of industrial strip malls in the East Side Detroit suburb of Warren, the Ritz doesn't seem like a setting for launching successful careers. Yet, according to club management, Detroit artists like Eminem (who, during his infamous early Slim Shady days, allegedly pistol whipped a guy there during a dispute involving then wife Kim Mathers) and Kid Rock honed their acts on its dank, sweaty stage before catapulting into mainstream pop culture, so that it's no surprise that the somewhat stagnant jit scene would pick the Ritz's legendary but underrated dance floor as their weekly playground as it looks to rebuild its profile.Around 10:30 the music started to swell—some classic house came on the speakers, inviting the first jitters to warm up the dance circle. As the circle got bigger, the dancers egged each other on, with the help of a woman who, accompanied by booty house and ghettotech, challenged each jitter to work it: "you gotta work, you gotta work, you gotta work!" As the night rolled on, it became clear that jitting is largely a man's sport, save for a handful of women, who are unafraid to battle it out with the boys. The moves of girls like Shakera, a.k.a. Shake Sanders, and Micheala “Pro” Smith from Le'Jit Dance Company depend more on the gyrations of their asses, but these are not your typical club kids dressed in halters, platforms, or booty shorts. Jitting requires athleticism and focus, so they prefer to dress in sweats or yoga pants. “For us, we have to distinguish ourselves with a little bit of sex appeal, but at the end of the day we’re ladies,” Shakera later says at the premiere.At the Ritz, everyone was so cool with each other and chill that the atmosphere wasn't competitive but rather familial. This is a community that dances with their hearts, not just with their feet or bravado. It’s an expression of an old school soul that can be traced back to the dancefloors of the 70s, where some jitters' parents danced the Soul Train nights away. Local jitter “Breeze” recalls watching his elegant mother and father dancing years ago and the influence remains strong today. The overwhelming feeling of tradition tying those early years profiled in Stringz's documentary to the present is part of why jit remains important even if it persists outside of a bigger spotlight. While it's still a phenomenon untouched by commercialism and is practiced at places like The Ritz—the unfortunate but perhaps logical result of being tied to such an undefinable style of music—it thrives as a as a movement that depends on rich history and sense of community, which is increasingly rare in the era of genre homogenization and rapid online appropriation. This lineage was evident Friday evening when the dozens of jitterbugs received a standing ovation following their performance from an audience of Detroiters from all walks of life proudly paying their respect to an artform that's stayed true to its Detroit roots.For more information about the documentary The Jitterbugs: Pioneers of the Jit click here.Serena Maria Daniels and Maximilian de la Garza are writers living in Detroit. They're on Twitter - @serenamaria36 and @johnnietruant--Want more dance music?Remembering DJ Rashad10 Rave Classics That Took the Pop ChartsTotal Freedom Won't Let You Dance

Stringz / Photo by Lena LeeWith initiatives like the documentary, his outreach work, and his own dance crew, Stringz is fighting against shunting aside of the art form. We followed him one recent Monday night, at his studio, which also serves as an inner city youth summer camp activity hall, with a worn concrete floor with painted on cobble stones, tall ballerina mirrors and a mix of rudimentary murals and graffiti art painted on the walls. Little by little, Stringz greeted crew members and they started breaking. The crew is made up of teenage white boys from the suburbs, Iraqi immigrants seeking asylum in Metro Detroit, and a handful of b-girls, among others. They threw on knitted beanie hats and got to work on head spins, windmill swipes and freezes, while hard techno and funk blasted from an amplified iPhone's playlist.After the practice session, we headed over to The Ritz, just as DJ Row was setting up his equipment. He's been on the scene since the early 90s, back when jitters were doing their moves at Northland Roller Rink. On this night, he was gearing up for Open Circle Mondays, where veteran jit dancers and newcomers alike can showcase and battle. At first glance the Ritz looks and feels like your run-of-the-mill Midwestern dive-club shithole, the kind of place where you order Bud Lights by the bucketful and meet up with coworkers from the nearby GM and Chrysler plants for happy hour or to watch grungy garage bands. Surrounded by acres of industrial strip malls in the East Side Detroit suburb of Warren, the Ritz doesn't seem like a setting for launching successful careers. Yet, according to club management, Detroit artists like Eminem (who, during his infamous early Slim Shady days, allegedly pistol whipped a guy there during a dispute involving then wife Kim Mathers) and Kid Rock honed their acts on its dank, sweaty stage before catapulting into mainstream pop culture, so that it's no surprise that the somewhat stagnant jit scene would pick the Ritz's legendary but underrated dance floor as their weekly playground as it looks to rebuild its profile.Around 10:30 the music started to swell—some classic house came on the speakers, inviting the first jitters to warm up the dance circle. As the circle got bigger, the dancers egged each other on, with the help of a woman who, accompanied by booty house and ghettotech, challenged each jitter to work it: "you gotta work, you gotta work, you gotta work!" As the night rolled on, it became clear that jitting is largely a man's sport, save for a handful of women, who are unafraid to battle it out with the boys. The moves of girls like Shakera, a.k.a. Shake Sanders, and Micheala “Pro” Smith from Le'Jit Dance Company depend more on the gyrations of their asses, but these are not your typical club kids dressed in halters, platforms, or booty shorts. Jitting requires athleticism and focus, so they prefer to dress in sweats or yoga pants. “For us, we have to distinguish ourselves with a little bit of sex appeal, but at the end of the day we’re ladies,” Shakera later says at the premiere.At the Ritz, everyone was so cool with each other and chill that the atmosphere wasn't competitive but rather familial. This is a community that dances with their hearts, not just with their feet or bravado. It’s an expression of an old school soul that can be traced back to the dancefloors of the 70s, where some jitters' parents danced the Soul Train nights away. Local jitter “Breeze” recalls watching his elegant mother and father dancing years ago and the influence remains strong today. The overwhelming feeling of tradition tying those early years profiled in Stringz's documentary to the present is part of why jit remains important even if it persists outside of a bigger spotlight. While it's still a phenomenon untouched by commercialism and is practiced at places like The Ritz—the unfortunate but perhaps logical result of being tied to such an undefinable style of music—it thrives as a as a movement that depends on rich history and sense of community, which is increasingly rare in the era of genre homogenization and rapid online appropriation. This lineage was evident Friday evening when the dozens of jitterbugs received a standing ovation following their performance from an audience of Detroiters from all walks of life proudly paying their respect to an artform that's stayed true to its Detroit roots.For more information about the documentary The Jitterbugs: Pioneers of the Jit click here.Serena Maria Daniels and Maximilian de la Garza are writers living in Detroit. They're on Twitter - @serenamaria36 and @johnnietruant--Want more dance music?Remembering DJ Rashad10 Rave Classics That Took the Pop ChartsTotal Freedom Won't Let You Dance

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement