Photo by Daniel PatlánIn 1629, Mexico City flooded, and it remained partially underwater for five years. Think about that! Five years! That’s longer than the entirety of high school. Imagine all the 1629-era teens who never got to go to prom because not only would it be expensive to rent a limo, but also, oh yeah, the city was flooded. Imagine being a Spanish colonist who had gone away for a little while and couldn’t wait to come back and visit his favorite torta spot but then couldn’t find it not only because any city is bound to change over the course of five years but also because it was submerged in water. In 1629 years, five years was a significant portion of someone’s life. But then, I imagine, the water receded and life went on and the five-year flood gradually condensed itself in people’s memories because that’s the way that time works. The flood inevitably must have become something that people didn’t really think about as much, that they referred to in passing: Remember that crazy party, you know, back when the city was flooded? Oh yeah, I used to hang out with that guy a lot around the time the city was underwater. Et cetera. Like anything else, a five-year flood presumably just becomes a phase in your life. Photo by Daniel PatlánWhat does this flood have to do with my own trip to Mexico City last weekend, 480 years after it dissipated, for the Corona Capital music festival? Well, there were thunderstorms every night of my stay, and the festival, as a result, turned into a churned up morass of mud and muddy water that was several inches deep in some places. The grass inside of and around the F1 race track where the festival was held disappeared, turned to a soupy sludge that stuck to everyone’s shoes, and became a landscaping challenge that will probably take five somethings—days? weeks? months? years?—to fix. The rain drove us away from watching Jack White and MGMT perform on the first night. The mud and the eight-inch-deep pools of water tired us out too much to stay for Kings of Leon and Lykke Li the second night. It was our own flood. But that five-year flood was also on my mind because it doesn’t take a massive natural disaster to create life phases.

Photo by Daniel PatlánWhat does this flood have to do with my own trip to Mexico City last weekend, 480 years after it dissipated, for the Corona Capital music festival? Well, there were thunderstorms every night of my stay, and the festival, as a result, turned into a churned up morass of mud and muddy water that was several inches deep in some places. The grass inside of and around the F1 race track where the festival was held disappeared, turned to a soupy sludge that stuck to everyone’s shoes, and became a landscaping challenge that will probably take five somethings—days? weeks? months? years?—to fix. The rain drove us away from watching Jack White and MGMT perform on the first night. The mud and the eight-inch-deep pools of water tired us out too much to stay for Kings of Leon and Lykke Li the second night. It was our own flood. But that five-year flood was also on my mind because it doesn’t take a massive natural disaster to create life phases. Photo by Daniel PatlánThere are all kinds of dividers of time and markers of change—jobs, places, people, smells, sounds—that define your existence and your habits every day until, at some point, they don’t anymore. This is how we tend to remember music, too: by where we were, what we were doing, how we felt when we first heard it or obsessively listened to it. We have our Bruce Springsteen phase or our 60s soul phase or our phase where we listened to the Burial album every night before we fell asleep. Songs are signposts for our memories, little reminders of "hey, don't let that moment when you were driving to New York and imagining your life there slide away; just remember that you were listening to Tim McGraw." Music is a great marker of time: You love Kings of Leon not because you used to drive around listening to them but during your junior year of college, sharing them with your new best friend who you loved so intensely but who would go on, in another phase, to not be your best friend anymore. Or maybe you don’t give a shit about Kings of Leon, but you still remember how you used to hear “Sex on Fire” come on the radio all the time when you used to work at the gym because they played it on both the mainstream rock station and the indie rock public radio station, and your best friend insisted that Kings of Leon were actually awesome if you listened to their first couple albums. But then that phase passes away, becomes something you just mention sometimes, that summer you spent working at the gym. That summer you actually spent most of your time listening to, of all things, the Pains of Being Pure at Heart, and you told your then-new girlfriend about Drake, who was about to become famous.

Photo by Daniel PatlánThere are all kinds of dividers of time and markers of change—jobs, places, people, smells, sounds—that define your existence and your habits every day until, at some point, they don’t anymore. This is how we tend to remember music, too: by where we were, what we were doing, how we felt when we first heard it or obsessively listened to it. We have our Bruce Springsteen phase or our 60s soul phase or our phase where we listened to the Burial album every night before we fell asleep. Songs are signposts for our memories, little reminders of "hey, don't let that moment when you were driving to New York and imagining your life there slide away; just remember that you were listening to Tim McGraw." Music is a great marker of time: You love Kings of Leon not because you used to drive around listening to them but during your junior year of college, sharing them with your new best friend who you loved so intensely but who would go on, in another phase, to not be your best friend anymore. Or maybe you don’t give a shit about Kings of Leon, but you still remember how you used to hear “Sex on Fire” come on the radio all the time when you used to work at the gym because they played it on both the mainstream rock station and the indie rock public radio station, and your best friend insisted that Kings of Leon were actually awesome if you listened to their first couple albums. But then that phase passes away, becomes something you just mention sometimes, that summer you spent working at the gym. That summer you actually spent most of your time listening to, of all things, the Pains of Being Pure at Heart, and you told your then-new girlfriend about Drake, who was about to become famous. Stuart Murdoch of Belle & Sebastian / Photo by Bruno MuñozMexico was inevitably going to be part of a phase of some sort, and, given the lineup of Corona Capital, which was heavy on indie rock bands that had played roles of varying importance in my life over the last decade-plus, it was also inevitably going to be a revisiting of certain phases. You don’t just show up at a Belle & Sebastian set in 2014 without some sort of Belle & Sebaggage. Then again, you may find that dancing to “Another Sunny Day” is actually more fun now than it ever was to drive around listening to that song in high school, even though you haven’t paid attention to that band in close to a decade. If Gorillaz was your favorite thing ever in eighth grade, you don’t ignore Damon Albarn, although perhaps you would have been better off doing so, to avoid standing in the mud through a half-dozen songs you’ve never heard before giving up. White Denim may not play any of the songs you listened to obsessively that one fall that you were really into them, but their noodly slacker butt rock will still bring back the feeling of being an eager, confused new arrival in a big city, and you will still wish you could text your friend who they remind you of (you can’t because you are in Mexico, and that is not on your phone plan).

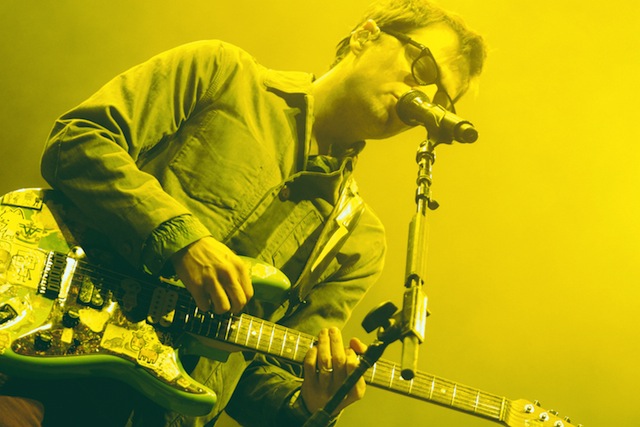

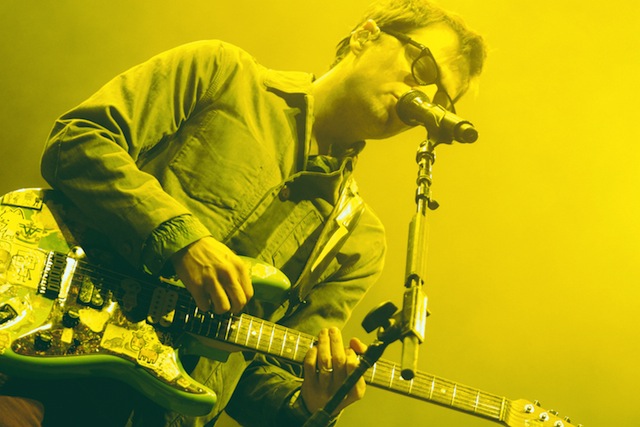

Stuart Murdoch of Belle & Sebastian / Photo by Bruno MuñozMexico was inevitably going to be part of a phase of some sort, and, given the lineup of Corona Capital, which was heavy on indie rock bands that had played roles of varying importance in my life over the last decade-plus, it was also inevitably going to be a revisiting of certain phases. You don’t just show up at a Belle & Sebastian set in 2014 without some sort of Belle & Sebaggage. Then again, you may find that dancing to “Another Sunny Day” is actually more fun now than it ever was to drive around listening to that song in high school, even though you haven’t paid attention to that band in close to a decade. If Gorillaz was your favorite thing ever in eighth grade, you don’t ignore Damon Albarn, although perhaps you would have been better off doing so, to avoid standing in the mud through a half-dozen songs you’ve never heard before giving up. White Denim may not play any of the songs you listened to obsessively that one fall that you were really into them, but their noodly slacker butt rock will still bring back the feeling of being an eager, confused new arrival in a big city, and you will still wish you could text your friend who they remind you of (you can’t because you are in Mexico, and that is not on your phone plan). Rivers Cuomo / Photo by Bruno MuñozMy Weezer phase, like many people’s Weezer phases, was in high school, when I downloaded five or six songs of theirs off of Kazaa. I knew those songs—“Island in the Sun,” “Buddy Holly,” “Say It Ain’t So,” “Hash Pipe,” “Undone (The Sweater Song)”—pretty well, but I also had no sense of context as far as who Weezer were, and I didn’t realize until much later what exactly Weezer meant to the rest of the world. It turns out that Weezer is huge in Mexico, and Rivers Cuomo is a very good entertainer. He bantered with the crowd in Spanish and covered Mexican singer Ana Gabriel’s 1989 hit “Quien Como Tu” to an enthusiastic reaction. He led into “Island in the Sun” by talking about vacationing in Mexico and looking for “una isla en el sol.” It was a fun way to lead into a song, and even I (or maybe particularly I, with my limited Spanish) was thrilled into rabid cheering. “Beverly Hills” chugged its way up to a giant sing-along because, despite the received wisdom that that song sucked when it came out, it is a major jam. Weezer kind of shreds, and even though the song they did with Bethany Cosentino from their new album was terrible, the instrumental section they played from their new album was pretty sweet.

Rivers Cuomo / Photo by Bruno MuñozMy Weezer phase, like many people’s Weezer phases, was in high school, when I downloaded five or six songs of theirs off of Kazaa. I knew those songs—“Island in the Sun,” “Buddy Holly,” “Say It Ain’t So,” “Hash Pipe,” “Undone (The Sweater Song)”—pretty well, but I also had no sense of context as far as who Weezer were, and I didn’t realize until much later what exactly Weezer meant to the rest of the world. It turns out that Weezer is huge in Mexico, and Rivers Cuomo is a very good entertainer. He bantered with the crowd in Spanish and covered Mexican singer Ana Gabriel’s 1989 hit “Quien Como Tu” to an enthusiastic reaction. He led into “Island in the Sun” by talking about vacationing in Mexico and looking for “una isla en el sol.” It was a fun way to lead into a song, and even I (or maybe particularly I, with my limited Spanish) was thrilled into rabid cheering. “Beverly Hills” chugged its way up to a giant sing-along because, despite the received wisdom that that song sucked when it came out, it is a major jam. Weezer kind of shreds, and even though the song they did with Bethany Cosentino from their new album was terrible, the instrumental section they played from their new album was pretty sweet. Weezer / Photo by Bruno MuñozIt’s an odd period for Weezer right now, the one in which they accept that they are mostly a nostalgia act but they also keep making whatever the hell records they feel like. You have to admire them, if only for being a band on which tons of people place expectations and that has no concern for fulfilling those expectations. Weezer is open to phases: Life changes, Weezer changes, and the past stays more or less the same, changing only slightly in the way we remember it as different things, different songs, bring it back and brighten it up. You might have felt uncool in high school, but, looking back, you’re more likely to remember how sweet it felt listening to “Buddy Holly” when you were hanging out in the car in front of your favorite lunch spot. I can only imagine the terrible mosquitoes that a five-year flood might bring, but, once a five-year flood is in the past, you probably just end up nostalgic for that one time you went canoeing through your friend’s house. Maybe it drove you nuts that your ex-girlfriend always got mad at you for being late to things, but, watching her sing along to “My Name Is Jonas,” how could you feel anything except an eternal crush on her? Oh yeah, the period after the end of a relationship. Maybe that’s a phase that’s happening right now, while you are in Mexico.

Weezer / Photo by Bruno MuñozIt’s an odd period for Weezer right now, the one in which they accept that they are mostly a nostalgia act but they also keep making whatever the hell records they feel like. You have to admire them, if only for being a band on which tons of people place expectations and that has no concern for fulfilling those expectations. Weezer is open to phases: Life changes, Weezer changes, and the past stays more or less the same, changing only slightly in the way we remember it as different things, different songs, bring it back and brighten it up. You might have felt uncool in high school, but, looking back, you’re more likely to remember how sweet it felt listening to “Buddy Holly” when you were hanging out in the car in front of your favorite lunch spot. I can only imagine the terrible mosquitoes that a five-year flood might bring, but, once a five-year flood is in the past, you probably just end up nostalgic for that one time you went canoeing through your friend’s house. Maybe it drove you nuts that your ex-girlfriend always got mad at you for being late to things, but, watching her sing along to “My Name Is Jonas,” how could you feel anything except an eternal crush on her? Oh yeah, the period after the end of a relationship. Maybe that’s a phase that’s happening right now, while you are in Mexico. Photo by Daniel PatlánA music festival itself can become, or at least represent, a phase: The trip where you found yourself giddily in love with your new girlfriend, excitedly taking in the music that she loved, the pair of you banding together amid all those strangers like two dusty outlaws; the festival where you excitedly returned to the city where you used to live with that same girl and the two of you ate long, relaxed breakfasts together; the time you went to a festival alone and had a devastating bout of miscommunication that you wish you could go back and undo. Or the time you end up in another country after a breakup, wondering how you’re going to navigate the rest of your life and uncertain about pretty much everything except how great music is. And maybe you’re doing that with your ex, which is its own whole thing to deal with, and here you two are listening to Zedd play “Clarity” as it rains, and you’re surrounded by 30,000 people chanting along to the “ohhh, ohhhh” parts while you personally are wondering if this person is your clarity and also how one song could be so enormous and so true at the same time. And there’s only one way that situation ends, honestly—a real-life drop—where you ultimately only want one thing, which is to kiss her, which you do. Music segments your life into phases, and this single moment of pure, raw emotion, this is your Zedd phase.

Photo by Daniel PatlánA music festival itself can become, or at least represent, a phase: The trip where you found yourself giddily in love with your new girlfriend, excitedly taking in the music that she loved, the pair of you banding together amid all those strangers like two dusty outlaws; the festival where you excitedly returned to the city where you used to live with that same girl and the two of you ate long, relaxed breakfasts together; the time you went to a festival alone and had a devastating bout of miscommunication that you wish you could go back and undo. Or the time you end up in another country after a breakup, wondering how you’re going to navigate the rest of your life and uncertain about pretty much everything except how great music is. And maybe you’re doing that with your ex, which is its own whole thing to deal with, and here you two are listening to Zedd play “Clarity” as it rains, and you’re surrounded by 30,000 people chanting along to the “ohhh, ohhhh” parts while you personally are wondering if this person is your clarity and also how one song could be so enormous and so true at the same time. And there’s only one way that situation ends, honestly—a real-life drop—where you ultimately only want one thing, which is to kiss her, which you do. Music segments your life into phases, and this single moment of pure, raw emotion, this is your Zedd phase. Photo by Daniel PatlánImagine the point in the five-year flood where you kind of begin to realize that this change isn’t temporary, that this is your reality for the foreseeable future.My MØ phase isn’t really a thing, but I would be remiss if I didn’t mention that MØ delivered one of the weekend’s best sets, taking on the crowd with complete enthusiasm and thriving in a context where the massiveness and triumphantly unpredictable low end of her tracks could be fully appreciated at high volume. MØ is a pop star in the making, and, based on the reaction she got speaking with a crowd in their mutual second language (English), she is a global pop star. I am now in a MØ phase. The world is headed for a MØ phase.

Photo by Daniel PatlánImagine the point in the five-year flood where you kind of begin to realize that this change isn’t temporary, that this is your reality for the foreseeable future.My MØ phase isn’t really a thing, but I would be remiss if I didn’t mention that MØ delivered one of the weekend’s best sets, taking on the crowd with complete enthusiasm and thriving in a context where the massiveness and triumphantly unpredictable low end of her tracks could be fully appreciated at high volume. MØ is a pop star in the making, and, based on the reaction she got speaking with a crowd in their mutual second language (English), she is a global pop star. I am now in a MØ phase. The world is headed for a MØ phase. Sam Smith / Photo courtesy of Corona CapitalThe truest and most global of the pop stars, though, was Sam Smith, who has many songs that people like to sing along to and two songs in particular that are some of the biggest hits in the world right now. He’s a gracious performer, and he seems like a genuinely nice guy who deserves all the success he gets. It seems inevitable that his veneer of cool will wear off soon, but for now Sam Smith is someone we all can unite around. We can get on board with Sam Smith because one of his two hit songs, “Latch,” is a wildly fun Disclosure song that makes people lose their minds when Zedd drops it into a set, as well as a slow love ballad that carries a hint of tragedy when he sings it in his own sets. We can fall deeply into the world of his other hit song, “Stay With Me,” because it is an incredibly poignant, well-written take on post-relationship malaise—“lay with me so it doesn’t hurt”—that also happens to have a huge chorus that everyone can sing and wave their arms to no matter their level of identification with the lyrics.

Sam Smith / Photo courtesy of Corona CapitalThe truest and most global of the pop stars, though, was Sam Smith, who has many songs that people like to sing along to and two songs in particular that are some of the biggest hits in the world right now. He’s a gracious performer, and he seems like a genuinely nice guy who deserves all the success he gets. It seems inevitable that his veneer of cool will wear off soon, but for now Sam Smith is someone we all can unite around. We can get on board with Sam Smith because one of his two hit songs, “Latch,” is a wildly fun Disclosure song that makes people lose their minds when Zedd drops it into a set, as well as a slow love ballad that carries a hint of tragedy when he sings it in his own sets. We can fall deeply into the world of his other hit song, “Stay With Me,” because it is an incredibly poignant, well-written take on post-relationship malaise—“lay with me so it doesn’t hurt”—that also happens to have a huge chorus that everyone can sing and wave their arms to no matter their level of identification with the lyrics. Photo by Daniel PatlánPretty much no matter where you are in life or on Earth right now, you are capable of having a Sam Smith phase, which is why “Stay With Me” is one of the biggest songs in the world. It’s a song that’s possible to love because you deeply identify with it or simply because Sam Smith has a beautiful voice. It’s a song that invites a future of familiarity, that already foreshadows Sam Smith’s success as a jazzy classic crooner playing a nightly gig in Vegas, because it is already so instantly recognizable. We will always not want the other person to leave. We will always want the other person to hold our hand. It’s kind of cheesy, but that’s why it works, because the best music expresses the things that we might feel too stupid or corny or timid to actually say out loud. The best music tends to be the music that finds us in a phase we ourselves maybe haven’t quite come to terms with yet, that begins to shape our swooshing undercurrents of emotion or identify the fleeting shape of a phase just out of our field of vision. That’s another thing about phases: They’re rarely neat or easily identifiable until after the fact. The floodwaters recede incredibly slowly. But they do, I guess, and so does everything else. You wake up, you pack your bags, you begin to feel nostalgic. You find yourself keeping your festival wristband because you want some physical memory. You get on a plane. You listen to the song she sent you.Follow Kyle Kramer on Twitter.

Photo by Daniel PatlánPretty much no matter where you are in life or on Earth right now, you are capable of having a Sam Smith phase, which is why “Stay With Me” is one of the biggest songs in the world. It’s a song that’s possible to love because you deeply identify with it or simply because Sam Smith has a beautiful voice. It’s a song that invites a future of familiarity, that already foreshadows Sam Smith’s success as a jazzy classic crooner playing a nightly gig in Vegas, because it is already so instantly recognizable. We will always not want the other person to leave. We will always want the other person to hold our hand. It’s kind of cheesy, but that’s why it works, because the best music expresses the things that we might feel too stupid or corny or timid to actually say out loud. The best music tends to be the music that finds us in a phase we ourselves maybe haven’t quite come to terms with yet, that begins to shape our swooshing undercurrents of emotion or identify the fleeting shape of a phase just out of our field of vision. That’s another thing about phases: They’re rarely neat or easily identifiable until after the fact. The floodwaters recede incredibly slowly. But they do, I guess, and so does everything else. You wake up, you pack your bags, you begin to feel nostalgic. You find yourself keeping your festival wristband because you want some physical memory. You get on a plane. You listen to the song she sent you.Follow Kyle Kramer on Twitter.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement